Roller chain

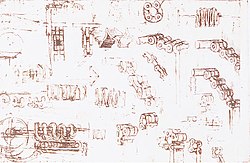

The original power transmission chain varieties lacked rollers and bushings, with both the inner and outer plates held by pins which directly contacted the sprocket teeth; however this configuration exhibited extremely rapid wear of both the sprocket teeth and the plates where they pivoted on the pins.

This distributed the wear over a greater area; however the teeth of the sprockets still wore more rapidly than is desirable, from the sliding friction against the bushings.

Continuous, clean, lubrication of roller chains is of primary importance for efficient operation, as is correct tensioning.

[5] Many driving chains (for example, in factory equipment, or driving a camshaft inside an internal combustion engine) operate in clean environments, and thus the wearing surfaces (that is, the pins and bushings) are safe from precipitation and airborne grit, many even in a sealed environment such as an oil bath.

O-rings were included as a way to improve lubrication to the links of power transmission chains, a service that is vitally important to extending their working life.

These rubber fixtures form a barrier that holds factory applied lubricating grease inside the pin and bushing wear areas.

Further, the rubber o-rings prevent dirt and other contaminants from entering inside the chain linkages, where such particles would otherwise cause significant wear.

Many oil-based lubricants attract dirt and other particles, eventually forming an abrasive paste that will compound wear on chains.

This problem can be reduced by use of a "dry" PTFE spray, which forms a solid film after application and repels both particles and moisture.

Motorcycle chains are part of the drive train to transmit the motor power to the back wheel.

Timing chains on automotive engines, for example, typically have multiple rows of plates called strands.

[10] A horseshoe clip is the U-shaped spring steel fitting that holds the side-plate of the joining (or "master") link formerly essential to complete the loop of a roller chain.

The clip method is losing popularity as more and more chains are manufactured as endless loops not intended for maintenance.

With modern materials and tools and skilled application this is a permanent repair having almost the same strength and life of the unbroken chain.

Note that this is due to wear at the pivoting pins and bushes, not from actual stretching of the metal (as does happen to some flexible steel components such as the hand-brake cable of a motor vehicle).

The sprockets (in particular the smaller of the two) suffer a grinding motion that puts a characteristic hook shape into the driven face of the teeth.

Only in very light-weight applications such as a bicycle, or in extreme cases of improper tension, will the chain normally jump off the sprockets.

The lightweight chain of a bicycle with derailleur gears can snap (or rather, come apart at the side-plates, since it is normal for the "riveting" to fail first) because the pins inside are not cylindrical, they are barrel-shaped.

Chain failure is much less of a problem on hub-geared systems since the chainline does not bend, so the parallel pins have a much bigger wearing surface in contact with the bush.

The hub-gear system also allows complete enclosure, a great aid to lubrication and protection from grit.

Roller chains operating on a continuous drive beyond these thresholds can and typically do fail prematurely via linkplate fatigue failure.

For example, the following table shows data from ANSI standard B29.1-2011 (precision power transmission roller chains, attachments, and sprockets)[11] developed by the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).