Roman Breviary

Monte Cassino in c. 1100 obtained a book titled Incipit Breviarium sive Ordo Officiorum per totam anni decursionem.

[2] From such references, and from others of a like nature, Quesnel gathers that by the word Breviarium was at first designated a book furnishing the rubrics, a sort of Ordo.

[2] The canonical hours of the Breviary owe their remote origin to the Old Covenant when God commanded the Aaronic priests to offer morning and evening sacrifices.

In the early days of Christian worship the Sacred Scriptures furnished all that was thought necessary, containing as it did the books from which the lessons were read and the psalms that were recited.

St Benedict in the 6th century drew up such an arrangement, probably, though not certainly, on the basis of an older Roman division which, though not so skilful, is the one in general use.

Gradually there were added to these psalter choir-books additions in the form of antiphons, responses, collects or short prayers, for the use of those not skilful at improvisation and metrical compositions.

Jean Beleth, a 12th-century liturgical author, gives the following list of books necessary for the right conduct of the canonical office: the Antiphonarium, the Old and New Testaments, the Passionarius (liber) and the Legendarius (dealing respectively with martyrs and saints), the Homiliarius (homilies on the Gospels), the Sermologus (collection of sermons) and the works of the Fathers, besides the Psalterium and the Collectarium.

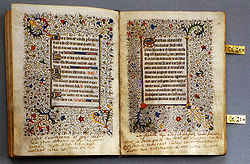

[1] The Breviary proper only dates from the 11th century; the earliest manuscript containing the whole canonical office is of the year 1099, and is in the Mazarin library.

There are several extant specimens of 12th-century Breviaries, all Benedictine, but under Innocent III (pope 1198–1216) their use was extended, especially by the newly founded and active Franciscan order.

These preaching friars, with the authorization of Gregory IX, adopted (with some modifications, e.g. the substitution of the "Gallican" for the "Roman" version of the Psalter) the Breviary hitherto used exclusively by the Roman court, and with it gradually swept out of Europe all the earlier partial books (Legendaries, Responsories), etc., and to some extent the local Breviaries, like that of Sarum.

Finally, Nicholas III (pope 1277–1280) adopted this version both for the curia and for the basilicas of Rome, and thus made its position secure.

[1] Before the rise of the mendicant orders (wandering friars) in the 13th century, the daily services were usually contained in a number of large volumes.

However, mendicant friars travelled frequently and needed a shortened, or abbreviated, daily office contained in one portable book, and single-volume breviaries flourished from the thirteenth century onwards.

These abbreviated volumes soon became very popular and eventually supplanted the Catholic Church's Curia office, previously said by non-monastic clergy.

In Scotland the only one which has survived the convulsions of the 16th century is Aberdeen Breviary, a Scottish form of the Sarum Office (the Sarum Rite was much favoured in Scotland as a kind of protest against the jurisdiction claimed by the diocese of York), revised by William Elphinstone (bishop 1483–1514), and printed at Edinburgh by Walter Chapman and Androw Myllar in 1509–1510.

This was inaugurated by Montalembert, but its literary advocates were chiefly Prosper Guéranger, abbot of the Benedictine monastery Solesmes, and Louis Veuillot (1813–1883) of the Univers.

The Jansenist and Gallican influence was also strongly felt in Italy and in Germany, where breviaries based on the French models were published at Cologne, Münster, Mainz and other towns.

Pius X was probably influenced by earlier attempts to eliminate repetition in the psalter, most notably the liturgy of the Benedictine congregation of St. Maur.

[3] In his apostolic letter Summorum Pontificum, Pope Benedict XVI allowed clerics to fulfill their obligation of prayer using the 1962 edition of the Roman Breviary in lieu of the Liturgy of the Hours.

[5] At the beginning stands the usual introductory matter, such as the tables for determining the date of Easter, the calendar, and the general rubrics.

[1] Before the 1911 reform, the multiplication of saints' festivals, with practically the same festal psalms, tended to repeat the about one-third of the Psalter, with a correspondingly rare recital of the remaining two-thirds.

[1] The hymns are short poems going back in part to the days of Prudentius, Synesius, Gregory of Nazianzus and Ambrose (4th and 5th centuries), but mainly the work of medieval authors.

Augustine, Hilary, Athanasius, Isidore, Gregory the Great and others, and formed part of the library of which the Breviary was the ultimate compendium.

They arise out of a primitive practice on the part of the bishop (local president), examples of which are found in the Didachē (Teaching of the Apostles) and in the letters of Clement of Rome and Cyprian.

The collects of the Breviary are largely drawn from the Gelasian and other Sacramentaries, and they are used to sum up the dominant idea of the festival in connection with which they happen to be used.

Additional help was given by a kind of Catholic Churchman's Almanack, called the Ordo Recitandi Divini Officii, published in different countries and dioceses, and giving, under every day, minute directions for proper reading.

[1] The late Medieval period saw the recitation of certain hours of the Little Office of the Blessed Virgin, which was based on the Breviary in form and content, becoming popular among those who could read, and Bishop Challoner did much to popularise the hours of Sunday Vespers and Compline (albeit in English translation) in his Garden of the Soul in the eighteenth century.

The Liturgical Movement in the twentieth century saw renewed interest in the Offices of the Breviary and several popular editions were produced, containing the vernacular as well as the Latin.

Two editions in English and Latin were produced in the following decade, which conformed to the rubrics of 1960, published by Liturgical Press and Benziger in the United States.

In 2008, a website containing the Divine Office (both Ordinary and Extraordinary) in various languages, i-breviary, was launched, which combines the modern and ancient breviaries with the latest computer technology.