Roman Vishniac

Roman Vishniac (/ˈvɪʃniæk/; Russian: Рома́н Соломо́нович Вишня́к; August 19, 1897 – January 22, 1990) was a Russian-American photographer, best known for capturing on film the culture of Jews in Central and Eastern Europe before the Holocaust.

[5] Roman Vishniac won international acclaim for his photos of shtetlach and Jewish ghettos, celebrity portraits, and microscopic biology.

His book A Vanished World, published in 1983, made him famous and is one of the most detailed pictorial documentations of Jewish culture in Eastern Europe in the 1930s.

In October 2018, Kohn donated the Vishniac archive of an estimated 30,000 items, including photo negatives, prints, documents and other memorabilia that had been housed at ICP to The Magnes Collection of Jewish Art and Life, a unit of the University of California at Berkeley's library system.

[10] On his seventh birthday, he got a microscope from his grandmother, to which he promptly hooked up a camera, and by which he photographed the muscles in a cockroach's leg at 150 times magnification.

Young Vishniac used this microscope extensively, viewing and photographing everything he could find, from dead insects to animal scales, to pollen and protozoa.

[10] As a graduate student, he worked with prestigious biologist Nikolai Koltzoff, experimenting with inducing metamorphosis in axolotl, a species of aquatic salamander.

While his experiments were a success, Vishniac was not able to publish a paper detailing his findings due to the chaos in Russia and his results were eventually independently duplicated.

[20] In his seventies and eighties, Vishniac became "Chevron Professor of Creativity" at Pratt Institute (where he taught courses on topics such as the philosophy of photography[15]).

During this time he lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with his wife Edith, teaching, photographing, reading and collecting artifacts.

[21] Items in his collection included a 14th-century Buddha, Chinese tapestries, Japanese swords, various antique microscopes, valued old maps and venerable books.

[2] He was commissioned to take these pictures by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC) as part of a fundraising initiative, but Vishniac had a personal interest in this subject matter.

[19] Later, when published, these photographs made him popular enough for his work to be showcased as one-man shows at Columbia University, the Jewish Museum in New York, the International Center of Photography and other such institutions.

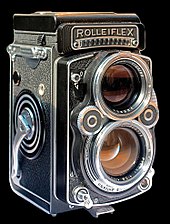

[2][27] To photograph small villages in these mountains, Vishniac claimed he carried heavy equipment (Leica, Rolleiflex, movie camera, tripods), 115 pounds (52 kilograms) by his estimate, on his back, up steep roads, trekking many miles.

[28] When using a Leica for indoor shots, Vishniac sometimes brought a kerosene lamp (visible in some of his work) if there was insufficient light, keeping his back to a wall for support, and holding his breath.

Roman Vishniac did not just want to preserve the memories of the Jews; he actively fought to increase awareness in the West of the worsening situation in Eastern Europe.

After photographing the "filthy barracks", as he described it, for two days,[29] he escaped by jumping from the second floor at night and creeping away, avoiding broken glass and barbed wire.

Vishniac's photographs from the 1930s are all of a very distinct style; they are all focused on achieving the same end: capturing the unique culture of Jewish ghettos in Eastern Europe, especially the religious and impoverished.

[2] His published pictures largely center on these people, usually in small groups, going about their daily lives: very often studying (generally religious texts), walking (many times through harsh weather), and sometimes just sitting; staring.

The eyes peer at us suspiciously from behind ancient casement windows and over a peddler's tray, from crowded schoolrooms and desolate street corners.

In the case of The Only Flowers of her Youth, the drama of the photograph inspired Miriam Nerlove to write a novel based on the story of the girl in the picture.

[5][10] In 1955 Edward Steichen selected three of Vishniac's Eastern European photographs; of boys at a Cheder in Slonim (1938), of children and a woman in Lublin (1937), for the Museum of Modern Art world-touring The Family of Man exhibition that was seen by 9 million visitors, accompanied by a catalogue which has never been out of print.

Thornton criticized his photographs for their unprofessional qualities, citing "errors of focus and accidents of design, as when an unexplained third leg and foot protrudes from the long coat of a hurrying scholar.

In the final spread of the book, for example, there is a photo of a man peering through a metal door; on the opposite page a small boy points with his finger to his eye.

[2] Benton also suggested that the terms of Vishniac's commission from the JDC – to photograph "not the fullness of Eastern European Jewish life but its most needy, vulnerable corners for a fund-raising project" – had led to his overemphasizing poor, religious communities in A Vanished World.

[5] One of Roman Vishniac's most famous endeavors in the field of photomicroscopy was his revolutionary photographs from the inside of a firefly's eye, behind 4,600 tiny ommatidia, complexly arranged.

[20] His method of colorization, (developed in the 1960s and early 1970s) uses polarized light to penetrate certain formations of cell structure and may greatly improve the detail of an image.

[5] In the field of biology, Vishniac specialized in marine microbiology, the physiology of ciliates, circulatory systems in unicellular plants and endocrinology (from his work in Berlin) and metamorphosis.

[20] Despite his aptitude and accomplishments in the field, most of his work in biology was secondary to his photography: Vishniac studied the anatomy of an organism primarily to better photograph it.

A famous photo of his (pictured right) of a store in Berlin selling devices for separating Jews and non-Jews by skull shape was used by him to criticize the pseudoscience of German anti-Semites.