Ancient Roman engineering

Summa crusta of silex or lava polygonal slabs, one to three feet in diameter and eight to twelve inches thick, were laid on top of the rudens.

Generally, when a road encountered an obstacle, the Romans preferred to engineer a solution to the obstacle rather than redirecting the road around it: bridges were constructed over all sizes of waterway; marshy ground was handled by the construction of raised causeways with firm foundations; hills and outcroppings were frequently cut or tunneled through rather than avoided (the tunnels were made with rectangle hard rock block).

Roman engineers used inverted siphons to move water across a valley if they judged it impractical to build a raised aqueduct.

Large diameter vertical wheels of Roman vintage, for raising water, have been excavated from the Rio Tinto mines in Southwestern Spain.

Several earthen dams are known from Britain, including a well-preserved example from Roman Lanchester, Longovicium, where it may have been used in industrial-scale smithing or smelting, judging by the piles of slag found at this site in northern England.

Tanks for holding water are also common along aqueduct systems, and numerous examples are known from just one site, the gold mines at Dolaucothi in west Wales.

Masonry dams were common in North Africa for providing a reliable water supply from the wadis behind many settlements.

Such massive public buildings were copied in numerous provincial capitals and towns across the empire, and the general principles behind their design and construction are described by Vitruvius writing at the turn of millennium in his monumental work De architectura.

The Romans were the first to exploit mineral deposits using advanced technology, especially the use of aqueducts to bring water from great distances to help operations at the pithead.

Their technology is most visible at sites in Britain such as Dolaucothi where they exploited gold deposits with at least five long aqueducts tapping adjacent rivers and streams.

It is highly likely that they also developed water-powered stamp mills to crush hard ore, which could be washed to collect the heavy gold dust.

Engineering was also institutionally ingrained in the Roman military, who constructed forts, camps, bridges, roads, ramps, palisades, and siege equipment amongst others.

One of the most notable examples of military bridge-building in the Roman Republic was Julius Caesar's bridge over the Rhine River.

Water wheel technology was developed to a high level during the Roman period, a fact attested both by Vitruvius (in De architectura) and by Pliny the Elder (in Naturalis Historia).

The largest complex of water wheels existed at Barbegal near Arles, where the site was fed by a channel from the main aqueduct feeding the town.

It is estimated that the site comprised sixteen separate overshot water wheels arranged in two parallel lines down the hillside.

[3] The capacity of the mills has been estimated at 4.5 tons of flour per day, sufficient to supply enough bread for the 12,500 inhabitants occupying the town of Arelate at that time.

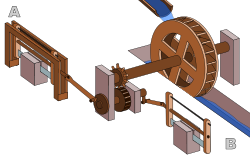

A waterwheel fed by a mill race is shown powering two frame saws via a gear train cutting rectangular blocks.

[7] Further crank and connecting rod mechanisms, without gear train, are archaeologically attested for the 6th-century AD water-powered stone sawmills at Gerasa, Jordan, and Ephesus, Turkey.

[8] Literary references to water-powered marble saws in Trier, now Germany, can be found in Ausonius's late 4th-century AD poem Mosella.

The Aurelian Walls were carried up the hill apparently to include the water mills used to grind grain towards providing bread flour for the city.