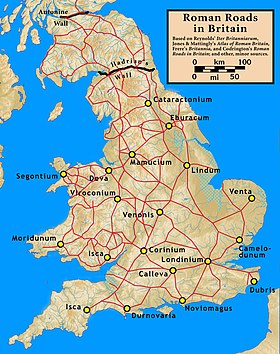

Roman roads in Britannia

The primary function of the network was to allow rapid movement of troops and military supplies, but it subsequently provided vital infrastructure for commerce, trade and the transportation of goods.

The Roman road network remained the only nationally managed highway system within Britain until the establishment of the Ministry of Transport in the early 20th century.

Main roads were gravel or paved, had bridges constructed in stone or wood, and manned waypoints where travellers or military units could stop and rest.

The earliest roads, built in the first phase of Roman occupation (the Julio-Claudian period, AD 43–68), connected London with the ports used in the invasion (Chichester and Richborough), and with the earlier legionary bases at Colchester, Lincoln (Lindum), Wroxeter (Viroconium), Gloucester and Exeter.

The Fosse Way, from Exeter to Lincoln, was also built at this time to connect these bases with each other, marking the effective boundary of the early Roman province.

During the Flavian period (AD 69–96), the roads to Lincoln, Wroxeter and Gloucester were extended (by CE 80) to the legionary bases at Eboracum (York), Deva Victrix (Chester) and Isca Augusta (Caerleon).

By 96, further extensions were completed from York to Corbridge, and from Chester to Luguvalium (Carlisle) and Segontium (Caernarfon) as Roman rule was extended over Cambria (Wales) and northern England (Brigantia).

Scotland (Caledonia), including England north of Hadrian's Wall, remained mostly outside the boundaries of Britannia province, as the Romans never succeeded in subjugating the entire island, despite a serious effort to do so by governor Gnaeus Julius Agricola in 82–84.

These eastern and southern routes acquired military importance from the 3rd century onwards with the emergence of Saxon seaborne raiding as a major and persistent threat to the security of Britannia.

These roads linked to the coastal defensive line of Saxon Shore forts such as Brancaster (Branodunum), Burgh Castle (Gariannonum) near Great Yarmouth, Lympne (Portus Lemanis) and Pevensey (Anderitum).

The metalling was in two layers, a foundation of medium to large stones covered by a running surface, often a compacted mixture of smaller flint and gravel.

Responsibility for their regular repair and maintenance rested with designated imperial officials (the curatores viarum), though the cost would probably have been borne by the local civitas (county) authorities whose territory the road crossed.

Despite the lack of any national management of the highways, Roman roads remained fundamental transport routes in England throughout the Early, High and Late Middle Ages.

[7] There are numerous tracts of Roman road which have survived, albeit overgrown by vegetation, in the visible form of footpaths through woodland or common land, such as the section of Stane Street crossing Eartham Wood in the South Downs near Bignor (Sussex).

Thus an urgent despatch from the army base at York to London – 200 mi (320 km), a journey of over a week for a normal mounted traveller – could be delivered in just 10 hours.

Approximately every 12 mi (19 km) – a typical day's journey for an ox-drawn wagon – was a mansio (literally: "a sojourn", from which derive the English word "mansion" and French maison or "house").

[8] At least half a dozen sites have been positively identified as mansiones in Britain, e.g. the excavated mansio at Godmanchester (Durovigutum) on Ermine Street (near Huntingdon, Cambridgeshire).

[9] Mutationes and mansiones were the key infrastructure for the cursus publicus (the imperial postal and transport system), which operated in many provinces of the Roman Empire.

Maps and Itineraries of the Roman era, designed to aid travellers, provide useful evidence of placenames, routes and distances in Britain.

As the Dover to London section of Watling Street was begun in the years following the Roman invasion of Britain in 43,[17] it may have been known to the Romano-Britons as the Via Claudia in honour of Emperor Claudius (41–54) who led the military campaign.

After Boudica's Revolt, London (Londinium) commanded the major bridge across the Thames connecting the final northern and western legionary bases with the Kentish ports communicating with Boulogne (Gesoriacum) and the rest of the Empire.