Roman siege engines

Up to the first century BC, the Romans utilized siege weapons only as required and relied for the most part on ladders, towers and rams to assault a fortified town.

The engineering corps was in charge of massive production, frequently prefabricating artillery and siege equipment to facilitate its transportation.

To support this effort, artillery attacks commence, with three main objectives:[3] to cause damage to defenses, casualties among the opposing army, and loss of enemy morale.

All were "predicated on a principle of physics: a lever was inserted into a skein of twisted horsehair to increase torsion, and when the arm was released, a considerable amount of energy was thus freed".

This included the hugely advantageous military advances the Greeks had made (most notably by Dionysus of Syracuse), as well as all the scientific, mathematical, political and artistic developments.

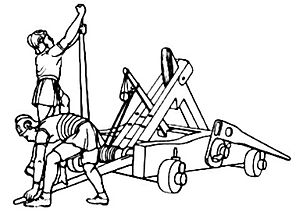

They were powered by two horizontal like arms, which were inserted into two vertical and tightly wound "skein" springs contained in a rectangular frame structure making up the head or principal part of the weapon.

[4] It has been said that the whirring sound of a ballista projected stone struck fear and dread into the hearts of those inside the walls of besieged cities.

A slider passed through the field frames of the weapon, in which were located the torsion springs (rope made of animal sinew), which were twisted around the bow arms, which in turn were attached to the bowstring.

The ballista was a highly accurate weapon (there are many accounts right from its early history of single soldiers being picked off by the operators), but some design aspects meant it could compromise its accuracy for range.

The lightweight bolts could not gain the high momentum of the stones over the same distance as those thrown by the later onagers, trebuchets, or mangonels; these could be as heavy as 90–135 kg (198–298 lb).

Both attempted invasions of Britain and the siege of Alesia are recorded in his own commentarii (journal), The Gallic Wars (De Bello Gallico).

The ships had to unload their troops on the beach, as it was the only one suitable for many kilometers, yet the massed ranks of British charioteers and javeliners were making it impossible.

Seeing this, Caesar ordered the warships – which were swifter and easier to handle than the transports, and likely to impress the natives more by their unfamiliar appearance – to be removed a short distance from the others, and then be rowed hard and run ashore on the enemy’s right flank, from which position the slings, bows and artillery could be used by men on deck to drive them back.

In the Middle Ages (recorded from around 1200 A.D.) a less powerful version of the onager was used that employed a fixed bowl rather than a sling, so that many small projectiles could be thrown, as opposed to a single large one.

[11] The moment they heard the ram hit the wall, those inside the city knew that the siege proper had begun and there was no turning back.

There is no tower strong enough nor any wall thick enough to withstand repeated blows of this kind, and many cannot resist the first shock.Vitruvius in De Architectura Book X describes the construction and use of battering rams.

[14] According to Apollodorus of Damascus, the shelter should be fixed to the ground while the ram was being used to both prevent skidding and strain on the axles from the weight of the moving apparatus.

Vegetius noted that, “besiegers sometimes built a tower with another turret inside it that could suddenly be raised by ropes and pulleys to over-top the wall”.

In chapter 1.22 "The Victory of Mylae" of his History, Polybius writes:Now their ships were badly fitted out and not easy to manage, and so some one suggested to them as likely to serve their turn in a fight the construction of what were afterwards called "crows".

[19] Corvus means "crow" or "raven" in Latin and was the name given to a Roman boarding device first documented during the First Punic War against Carthage.

[19]Based on this historical description the Corvus used some mechanisms seen in the more complex siege towers or the sheds constructed around battering rams.