History of the Jews in Romania

During his first years in office (1875) Brătianu reinforced and applied old discrimination laws, insisting that Jews were not allowed to settle in the countryside (and relocating those that had done so), while declaring many Jewish urban inhabitants to be vagrants and expelling them from the country.

[11] Military dictator Ion Antonescu eventually stopped the violence and chaos created by the Iron Guard by brutally suppressing the rebellion, but continued the policy of oppression and massacre of Jews, and, to a lesser extent, of Roma.

Isaac ben Benjamin Shor of Iași (Isak Bey, originally employed by Uzun Hassan) was appointed stolnic, being subsequently advanced to the rank of logofăt; he continued to hold this office under Bogdan the Blind (1504–1517), the son and successor of Stephen.

Through the efforts of Solomon Ashkenazi, Aron Tiranul was placed on the throne of Moldavia; nevertheless, the new ruler persecuted and executed nineteen Jewish creditors in Iași, who were decapitated without process of law.

[23] Massacres and forced conversions by the Cossacks occurred in 1652, when the latter came to Iași on the occasion of the Vasile Lupu's daughter marriage to Timush, the son of Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and during the rule of Gheorghe Ștefan.

[28] Overtaxed and persecuted under Ștefan Cantacuzino (1714–1716),[29] Wallachian Jews obtained valuable privileges during Nicholas Mavrocordatos' rule (1716–1730) in that country (the Prince notably employed the Jewish savant Daniel de Fonseca at his court).

The event was echoed in several contemporary chronicles and documents — for example, the French ambassador to the Porte, Jean-Baptiste Louis Picon, remarked that such an accusation was no longer accepted in "civilized countries".

When peace was restored, both princes, Alexander Mavrocordatos of Moldavia and Nicholas Mavrogheni of Wallachia, pledged their special protection to Jews, whose condition remained favorable until 1787, when both Janissaries and the Imperial Russian Army took part in pogroms.

[32] A seminal event occurred in 1804, when ruler Constantine Ypsilanti dismissed accusations of ritual murder as "the unfounded opinion" of "stupid people", and ordered that their condemnation be read in churches throughout Wallachia; the allegations no longer surfaced during the following period.

[30] During the Greek War of Independence, which signaled the Wallachian uprising of 1821 and the Danubian Principalities' occupation by Filiki Eteria troops under Alexander Ypsilantis, Jews were victims of pogroms and persecutions in places such as Fălticeni, Hertsa, Piatra Neamț, the Secu Monastery, Târgoviște, and Târgu Frumos.

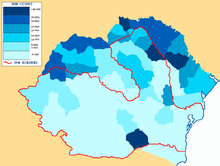

[33] Following the 1829 Treaty of Adrianople (which allowed the two principalities to freely engage in foreign trade), Moldavia, where commercial niches had been largely left unoccupied, became a target for migration of Ashkenazi Jews persecuted in Imperial Russia and the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria.

In various ways, Jews took part in the Wallachian revolt; for example, Constantin Daniel Rosenthal, the painter, distinguished himself in the revolutionary cause, and paid for his activity with his life (being tortured to death in Budapest by Austrian authorities).

[40] Following adoption of the 1859 regulation, soldiers and civilians would walk the streets of Iași and some other Moldavian towns, assaulting Jews, using scissors to shred their clothing, but also to cut their beards or their sidelocks; drastic measures applied by the Army Headquarters put a stop to such turmoil.

He proposed creating two chambers (of senators and deputies respectively), to extend the franchise to all citizens, and to emancipate the peasants from forced labor (expecting to nullify the remaining influence of the landowners – no longer boyars after the land reform).

In the process, Cuza also expected financial support from both the Jews and the Armenians – it appears that he kept the latter demand reduced, asking for only 40,000 Austrian florins (the standard gold coins; about US$ 90,000 at the exchange rate of the time) from the two groups.

A draft of a constitution was then submitted by the government, Article 6 of which declared that "religion is no obstacle to citizenship"; but, "with regard to the Jews, a special law will have to be framed in order to regulate their admission to naturalization and also to civil rights".

During his first years in office, Brătianu reinforced and applied old discrimination laws, insisting that Jews were not allowed to settle in the countryside (and relocating those that had done so), while declaring many Jewish urban inhabitants to be vagrants and expelling them from the country.

[46] When Brătianu resumed leadership, Romania faced the emerging conflict in the Balkans, and saw its chance to declare independence from Ottoman suzerainty by dispatching its troops on the Russian side in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

The war was concluded by the Treaty of Berlin (1878), which stipulated (Article 44) that the non-Christians in Romania (including both Jews and Muslims in the newly acquired region of Northern Dobruja) should receive full citizenship.

This was, however, reformulated to make procedures very difficult: "the naturalization of aliens not under foreign protection should in every individual case be decided by Parliament" (the action involved, among others, a ten-year term before the applicant was given an evaluation).

[48] Various laws were passed until the pursuit of virtually all careers was made dependent on the possession of political rights, which only Romanians could exercise; more than 40% of Jewish working men, including manual labourers, were forced into unemployment by such legislation.

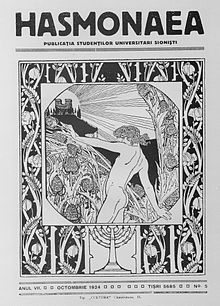

[51] During the same period, the anti-Jewish message first expanded beyond its National Liberal base (where it was soon an insignificant attitude),[52] to cover the succession of more radical and Moldavian-based organizations founded by A.C. Cuza (his Democratic Nationalist Party, created in 1910, had the first antisemitic program in Romanian political history).

[53] No longer present in the PNL's ideology by the 1920s, antisemitism also tended to surface in on the left-wing of the political spectrum, in currents originating in Poporanism – which favoured the claim that peasants were being systematically exploited by Jews.

The popularity of anti-Jewish messages was, nevertheless, on the rise, and merged itself with the appeal of fascism in the late 1920s – both contributed to the creation and success of Corneliu Zelea Codreanu's Iron Guard and the appearance of new types of anti-Semitic discourses (Trăirism and Gândirism).

[63] The threat posed by the Iron Guard, the emergence of Nazi Germany as a European power, and his own fascist sympathies [citation needed], made King Carol II, who was still largely identified as a philo-Semite,[64] adopt racial discrimination as the norm.

On February 12, 1938, he used the rising violence between political groups as context to seize absolute power (a move which was tacitly supported by the liberals who had come to view him as a lesser evil in comparison to Codreanu's fascist movement).

[citation needed] The King then arrested the entire leadership of the Iron Guard, on the grounds that they were in the pay of the Nazis, and began using the same accusation against various political opponents, both to solidify his absolute control of the country as well as negatively stigmatize Germany.

[11] Antonescu eventually stopped the violence and chaos created by the Iron Guard by brutally suppressing the rebellion, but continued the policy of oppression and massacre of Jews, and, to a lesser extent, of Roma.

Also, sometimes with the encouragement of Antonescu's regime, thirteen boats left Romania for the British Mandate of Palestine during the war, carrying 13,000 Jews (two of these ships were sunk by the Soviets (see Struma disaster), and the effort was discontinued after German pressure was applied).

[13] A majority of the Romanian Jews living within the 1940 borders did survive the war, although they were subject to a wide range of harsh conditions, including forced labor, financial penalties, and discriminatory law.