Romansh language

Romansh (/roʊˈmænʃ, roʊˈmɑːnʃ/ roh-MA(H)NSH; sometimes also spelled Romansch and Rumantsch)[note 1] is a Gallo-Romance and/or Rhaeto-Romance language spoken predominantly in the Swiss canton of the Grisons (Graubünden).

The Romansh language area can be described best as consisting of two widely divergent varieties, Sursilvan in the west and the dialects of the Engadine in the east, with Sutsilvan and Surmiran forming a transition zone between them.

Additionally, a small number of pre-Latin words have survived in Romansh, mainly concerning animals, plants, and geological features unique to the Alps, such as camutsch "chamois" and grava "scree".

[34] At the time, Romansh was spoken over a much wider area, stretching north into the present-day cantons of Glarus and St. Gallen, to the Walensee in the northwest, and Rüthi and the Alpine Rhine Valley in the northeast.

In a chronicle written in 1571–72, Durich Chiampell mentions that Romansh was still spoken in Chur roughly a hundred years before, but had since then rapidly given way to German and was now not much appreciated by the inhabitants of the city.

These early works are generally well written and show that the authors had a large amount of Romansh vocabulary at their disposal, contrary to what one might expect of the first pieces of writing in a language.

Because of this, the linguist Ricarda Liver assumes that these written works built on an earlier, pre-literature tradition of using Romansh in administrative and legal situations, of which no evidence survives.

Daniel Bonifaci produced the first surviving work in this category, the catechism Curt mussameint dels principals punctgs della Christianevla Religiun, published in 1601 in the Sutsilvan dialect.

In 1611, Igl Vêr Sulaz da pievel giuvan ("The true joys of young people"), a series of religious instructions for Protestant youths, was published by Steffan Gabriel.

Around the turn of the century, the inner Heinzenberg and Cazis became German-speaking, followed by Rothenbrunnen, Rodels, Almens, and Pratval, splitting the Romansh area into two geographically non-connected parts.

A key factor was the disinterest of the parents, whose main motivation for sending their children to the Scoletas appears to have been that they were looked after for a few hours and given a meal every day, rather than an interest in preserving Romansh.

[65] Early attempts to create a unified written language for Romansh include the Romonsch fusionau of Gion Antoni Bühler in 1867[66] and the Interrumantsch by Leza Uffer in 1958.

The elaboration of the new standard was endorsed by the Swiss National Fund and carried out by a team of young Romansh linguists under the guidance of Georges Darms and Anna-Alice Dazzi-Gross.

[83] The cantonal government refused to debate the issue again, instead deciding on a three-step plan in December 2004 to introduce Rumantsch Grischun as the language of schooling, allowing the municipalities to choose when they would make the switch.

[85] In 2007–2008, 23 so called "pioneer-municipalities" (Lantsch/Lenz, Brienz/Brinzauls, Tiefencastel, Alvaschein, Mon, Stierva, Salouf, Cunter, Riom-Parsonz, Savognin, Tinizong-Rona, Mulegns, Sur, Marmorera, Falera, Laax, Trin, Müstair, Santa Maria Val Müstair, Valchava, Fuldera, Tschierv and Lü) introduced Rumantsch Grischun as the language of instruction in 1st grade, followed by an additional 11 (Ilanz, Schnaus, Flond, Schluein, Pitasch, Riein, Sevgein, Castrisch, Surcuolm, Luven and Duvin) the following year and another 6 (Sagogn, Rueun, Siat, Pigniu, Waltensburg/Vuorz and Andiast) in 2009–2010.

[87] In early 2011, a group of opponents in the Surselva and the Engadine founded the association Pro Idioms, demanding the overturning of the government decision of 2003 and launching numerous local initiatives to return to the regional varieties as the language of instruction.

It remains an official and administrative language in the Swiss Confederation and the Canton of the Grisons as well as in public and private institutions for all kinds of texts intended for the whole Romansh-speaking territory.

The recognition of Romansh as the fourth national language is best seen within the context of the "Spiritual defence" preceding World War II, which aimed to underline the special status of Switzerland as a multinational country.

Following a referendum on March 10, 1996, Romansh was recognized as a partial official language of Switzerland alongside German, French, and Italian in article 70 of the federal constitution.

In general, though, demand for Romansh-language services is low because, according to the Federal Culture Office, Romansh speakers may either dislike the official Rumantsch Grischun idiom or prefer to use German in the first place, as most are perfectly bilingual.

[128] In the Sutselva, the local Romansh dialects are extinct in most villages, with a few elder speakers remaining in places such as Präz, Scharans, Feldis/Veulden, and Scheid, though passive knowledge is slightly more common.

Regular word order is subject–verb–object, but subject-auxiliary inversion occurs in several cases, placing the verb at the beginning of a sentence: These features are in close concord with German syntax, which has likely reinforced them.

Other Italian words include impostas "taxes" (← imposte; as opposed to Rhenish taglia), radunanza/radunonza "assembly" (← radunanza), Ladin ravarenda "(Protestant) priest" (← reverendo), bambin "Christmas child (giftbringer)" (← Gesù Bambino), marchadant/marcadont "merchant" (← mercatante) or butia/buteia "shop" (← bottega).

Whereas such verbs also occur sporadically in other Romance languages as in French prendre avec "to take along" or Italian andare via "to go away", the large number in Romansh suggests an influence of German, where this pattern is common.

The verbs far cun "to participate" or grodar tras "to fail" for example, are direct equivalents of German mitmachen (from mit "with" and machen "to do") and durchfallen (from durch "through" and fallen "to fall").

[158] Limited to Sursilvan is the insertion of entire phrases between auxiliary verbs and participles as in Cun Mariano Tschuor ha Augustin Beeli discurriu "Mariano Tschuor has spoken with Augustin Beeli" as compared to Engadinese Cun Rudolf Gasser ha discurrü Gion Peider Mischol "Rudolf Gasser has spoken with Gion Peider Mischol".

[158] Especially noticeable and often criticized by language purists are particles such as aber, schon, halt, grad, eba, or zuar, which have become an integral part of everyday Romansh speech, especially in Sursilvan.

[169] Common words of Romansh origin in Grisons-German include Spus/Spüslig "bridegroom" and Spus "bride", Banitsch "cart used for moving dung", and Pon "container made of wood".

[171] This view was prevalent until after World War II, with many contemporary linguists and activists by contrast seeing these loan elements as completely natural and as an integral part of Romansh,[172] which should be seen as an enrichment of the language.

The first substantial surviving work in Romansh is the Chianzun dalla guerra dagl Chiaste da Müs written in the Putèr dialect in 1527 by Gian Travers.

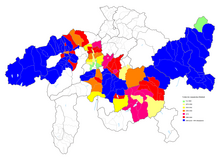

90–100% 75–90% 55–75%

45- 55% 25–45% 10–25%