Romanticism in Scotland

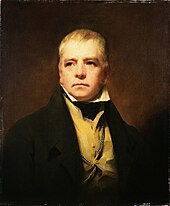

[1][2] In the arts, Romanticism manifested itself in literature and drama in the adoption of the mythical bard Ossian, the exploration of national poetry in the work of Robert Burns and in the historical novels of Walter Scott.

Romanticism was a complex artistic, literary and intellectual movement that originated in the second half of the eighteenth century in western Europe, and gained strength during and after the Industrial and French Revolutions.

[9] Although after union with England in 1707 Scotland increasingly adopted English language and wider cultural norms, its literature developed a distinct national identity and began to enjoy an international reputation.

Allan Ramsay (1684–1758) laid the foundations of a reawakening of interest in older Scottish literature, as well as leading the trend for pastoral poetry, helping to develop the Habbie stanza as a poetic form.

Claiming to have found poetry written by the ancient bard Ossian, he published translations that acquired international popularity, being proclaimed as a Celtic equivalent of the Classical epics.

His poem (and song) "Auld Lang Syne" is often sung at Hogmanay (the last day of the year), and "Scots Wha Hae" served for a long time as an unofficial national anthem of the country.

[18][19] Ian Duncan and Alex Benchimol suggest that publications like the novels of Scott and these magazines were part of a highly dynamic Scottish Romanticism that by the early nineteenth century, caused Edinburgh to emerge as the cultural capital of Britain and become central to a wider formation of a "British Isles nationalism.

Towards the end of the century there were "closet dramas", primarily designed to be read, rather than performed, including work by Scott, Hogg, Galt and Joanna Baillie (1762–1851), often influenced by the ballad tradition and Gothic Romanticism.

These highly popular plays saw the social range and size of the audience for theatre expand and helped shape theatre-going practices in Scotland for the rest of the century.

[27] Produced before his departure to Italy, Jacob More's (1740–93) series of four paintings "Falls of Clyde" (1771–73) have been described by art historian Duncan Macmillan as treating the waterfalls as "a kind of natural national monument" and has been seen as an early work in developing a romantic sensibility to the Scottish landscape.

He is most famous for his intimate portraits of leading figures in Scottish life, going beyond the aristocracy to lawyers, doctors, professors, writers and ministers,[29] adding elements of Romanticism to the tradition of Reynolds.

[41] In the 1790s Robert Burns embarked on an attempt to produce a corpus of Scottish national song, building on the work of antiquarians and musicologists such as William Tytler, James Beattie and Joseph Ritson.

[46] Max Bruch (1838–1920) composed the Scottish Fantasy (1880) for violin and orchestra, which includes an arrangement of the tune "Hey Tuttie Tatie", best known for its use in the song Scots Wha Hae by Burns.

[50] MacCunn's overture The Land of the Mountain and the Flood (1887), his Six Scotch Dances (1896), his operas Jeanie Deans (1894) and Dairmid (1897) and choral works on Scottish subjects[41] have been described by I. G. C. Hutchison as the musical equivalent of Abbotsford and Balmoral.

[53] An important element in the emergence of a Scottish national history was an interest in antiquarianism, with figures like John Pinkerton (1758–1826) collecting sources such as ballads, coins, medals, songs and artefacts.

[56] Patrick Fraser Tytler's nine-volume history of Scotland (1828–43), particularity his sympathetic view of Mary, Queen of Scots, have led to comparisons with Leopold von Ranke, considered the father of modern scientific historical writing.

[58] Issues of race became important, with Pinkerton, James Sibbald (1745–1803) and John Jamieson (1758–1839) subscribing to a theory of Picto-Gothicism, which postulated a Germanic origin for the Picts and the Scots language.

Romantic writers often reacted against the empiricism of Enlightenment historical writing, putting forward the figure of the "poet-historian" who would mediate between the sources of history and the reader, using insight to create more than chronicles of facts.

[65] Scott is now seen primarily as a novelist, but also produced a nine-volume biography of Napoleon,[66] and has been described as "the towering figure of Romantic historiography in Transatlantic and European contexts", having a profound effect on how history, particularly that of Scotland, was understood and written.

As defined by Susan Cannon, this form of inquiry placed a stress on observation, accurate scientific instruments and new conceptual tools; disregarded the boundaries between different disciplines; and emphasised working in nature rather than the artificial laboratory.

[71] James Allard identifies the origins of Scottish "Romantic medicine" in the work of Enlightenment figures, particularly the brothers William (1718–83) and John Hunter (1728–93), who were, respectively, the leading anatomist and surgeon of their day and in the role of Edinburgh as a major centre of medical teaching and research.

Brown argued in Elementa Medicinae (1780) that life is an essential "vital energy" or "excitability" and that disease is either the excessive or diminished redistribution of the normal intensity of the human organ, which became known as Brunonianism.

[82] His work was strongly influenced by transcendental anatomy, which, drawing on Goethe and Lorenz Oken (1779–1851),[83] looked for ideal patterns and structure in nature[84] and had been pioneered in Scotland by figures including Robert Knox (1791–1862).

[90] In the aftermath of the Jacobite risings, a movement to restore Stuart King James II of England to the throne, the British government enacted a series of laws that attempted to speed the process of the destruction of the clan system.

Tom Nairn argues that Romanticism in Scotland did not develop along the lines seen elsewhere in Europe, leaving a "rootless" intelligentsia, who moved to England or elsewhere and so did not supply a cultural nationalism that could be communicated to the emerging working classes.

[97] Graeme Moreton and Lindsay Paterson both argue that the lack of interference of the British state in civil society meant that the middle classes had no reason to object to the union.

[114] In art, the tradition of Scottish landscape painting continued into the later nineteenth century, but Romanticism gave way to influences including French Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and eventually Modernism.

[118] Common Sense Realism began to decline in Britain in the face of the English empiricism outlined by John Stuart Mill in his An Examination of Sir William Hamilton's Philosophy (1865).

[120] In Scott it produced a figure of international fame and influence, whose virtual invention of the historical novel would be picked up by writers across the world, including Alexandre Dumas and Honoré de Balzac in France, Leo Tolstoy in Russia and Alessandro Manzoni in Italy.

[61] Romantic science maintained the prominence and reputation that Scotland had begun to obtain in the Enlightenment and helped in the development of many emerging fields of investigation, including geology and biology.