Ronald L. Haeberle

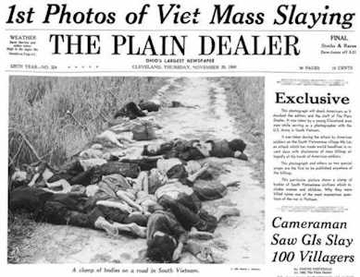

[2] On November 21, 1969, the day after the photographs were first published in Haeberle's hometown newspaper, The Cleveland Plain Dealer, Melvin Laird, the Secretary of Defense, discussed them with Henry Kissinger who was at the time National Security Advisor to President Richard Nixon.

[3][4][5] At the time of the massacre, Haeberle was a sergeant assigned as public information photographer to Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment.

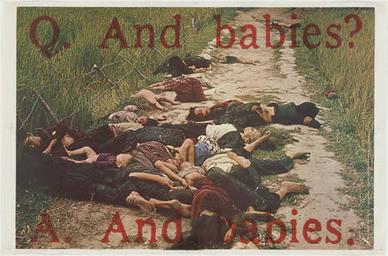

[7] One of Haeberle's photos became an important symbol of the massacre, in large part because of its use in the And babies poster, which was distributed around the world, reproduced in newspapers, and used in protest marches.

In fact, 1966 was the high water mark for the number of men who were inducted into the military through the Selective Service System, with over 380,000 drafted that year.

Here he took pictures of training exercises, award ceremonies and other facets of daily Army life which were published in the brigade newsletter.

[12] In fact, as Time magazine described it quoting him: "'We were told, "Life is meaningless to these people,"' he said, leaving unspoken the rest of that sentiment: The enemy is not like us.

"[2]On March 15, 1968, he was briefed about Charlie Company's planned operation the next day in the area near a small hamlet called My Lai.

[12] On November 20, 1969, when The Plain Dealer published his color photos and eye-witness account of what he had seen, the public in the United States and around the world was able to see and learn the shocking details of the massacre for the first time.

[21] Soldiers testified that their orders, as they understood them, were to kill all VC combatants and "suspects", including women and children, as well as all animals.

[22] When Charlie Company was briefed the night before, their commanding officer, Captain Ernest Medina was asked "Are we supposed to kill women and children?"

"[23] When Haeberle arrived in the area by helicopter he began moving forward with Charlie Company and was soon witnessing scenes he has "never been able to forget".

He personally witnessed U.S. soldiers mechanically kill as many as 100 Vietnamese civilians, "many of them women and babies, many left in lifeless clumps.

[1]: p.502 The Army Journalist, Specialist 5th Class Jay Roberts, who was with Haeberle that day, recalled the same scene and "stated that the older woman, who he presumed to be the girl’s mother, had been 'biting and kicking and scratching and fighting off' the group of soldiers.

"[28] Perhaps Time magazine described the impact of this photo best: "Haeberle’s picture of terror and distress on these faces, young and old, in the midst of slaughter remains one of the 20th century’s most powerful photographs.

When the Plain Dealer (and later, LIFE magazine) published it, along with a half-dozen others, the images graphically undercut much of what the U.S. had been claiming for years about the conduct and aims of the conflict.

"[2] On December 5, 1969, Walter Cronkite, on the CBS Evening News, issued a warning about disturbing images Haeberle's photos were broadcast.

.... Off to the left, a group of people—women, children, and babies.... and all of a sudden I heard this fire... [and he] had opened up on all these people in the big circle, and they were trying to run.

"[33]: pp.124&133 The official Army press dispatch on the operation said the VC body count was 128 and there was no mention of civilian casualties.

Private First Class Michael Bernhardt, who was there that day, would later testify, "I don't remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive.

The lead investigator told Haeberle details he didn't know: "babies, women, teens raped and mutilated."

"[32] Haeberle was criticized by the Army and Congressional investigations into the massacre for not reporting what he witnessed or turning in his color photographs.

[39] The congressional subcommittee "subjected Haeberle to exhaustive questioning" about why he failed to report what he had seen to his command, and they "badgered him about why he had been carrying" a personal camera and what he "intended to do with the pictures".

By chance, Haeberle had photographed that moment as well (see image on left with Duc on top protecting his sister Thu Ha Tran).

Haeberle said, "I have been committed to doing all I can to help the people of Vietnam ever since I personally witnessed American war crimes at My Lai.

"[44] The Vietnamese people and government have expressed their appreciation to Haeberle for helping to bring the massacre to the attention of the world, as well as for the humanitarian work he does in Vietnam.

On the 50th anniversary of the Paris Peace Accords (2013-2023), the Vietnam Union of Friendship Organizations presented Haeberle with an award "for peace and friendship among nations", honoring his contributions to helping to end the "US war in Vietnam, addressing the consequences of the war, [and] reconciling and promoting the Vietnam-US people-to-people exchanges.

[51][52] A large black marble plaque just inside the entrance to the museum lists the names of all 504 civilians killed by the American troops, including "17 pregnant women and 210 children under the age of 13.

[44] The images are dramatically backlit in color and share the central back wall with a life-size recreation of American soldiers "rounding up and shooting cowering villagers.

"[55] The museum also celebrates American heroes, including Ronald Ridenhour who first exposed the killings, as well as Hugh Thompson and Lawrence Colburn who intervened to save a number of villagers.

Murder, torture, rape, abuse, forced displacement, home burnings, specious arrests, imprisonment without due process — such occurrences were virtually a daily fact of life throughout the years of the American presence in Vietnam.