Seymour Hersh

[10] On October 22, 1969, Hersh received a tip from Geoffrey Cowan, a columnist for The Village Voice with a military source, about a soldier being held at Fort Benning in Georgia for a court-martial for allegedly killing 75 civilians in South Vietnam.

Together with Walter Rugaber, Hersh produced extensive reporting for the Times on the unfolding scandal; a key article by him published on January 14, 1973, revealed that hush money payments were still being made to the burglars, which shifted the press's focus from the break-in itself to its cover-up.

On June 11, 1972, an article by Hersh alleged that General John D. Lavelle, who had recently been relieved as commander of the Air Force in Southeast Asia, was ousted because he had ordered repeated, unauthorized bombings of North Vietnam.

[22] After reading Hersh's articles on the affair, Major Hal Knight, who had supervised radar crews in Vietnam, realized that the Senate "was unaware of what had taken place while I was out there", and in early 1973 wrote a letter to the committee that confessed his role in the cover-up of Operation Menu, in which he recorded fake bombing coordinates and burned his orders.

[26][27] On December 22, 1974, Hersh exposed Operation CHAOS, a massive CIA program of domestic wiretapping and infiltration of anti-war groups during the Nixon administration, which was conducted in direct violation of the agency's charter.

It was later revealed that Dick Cheney, one of Ford's top aides and later George W. Bush's vice president, proposed that the FBI search the home of Hersh and his sources in order to halt his reporting on the subject.

He began working on larger projects; the first was a four-part investigation produced with Jeff Gerth, initially appearing on June 27, 1976, into the activities of Sidney Korshak, a lawyer and "fixer" for the Chicago Mafia, union leaders, and Hollywood.

[32] On July 24, 1977, the Times published the first entry in a three-part investigation by Hersh and Gerth into financial impropriety at Gulf and Western Industries, one of the country's largest conglomerates; it was followed by two civil lawsuits by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The Times management was ambivalent about Hersh's new focus (he later stated that the paper "wasn't nearly as happy when we went after business wrongdoing as when we were kicking around some slob in government"), and he left the job in 1979 to start writing a book on Henry Kissinger.

[33] In 1981, an article by Hersh in The New York Times Magazine described how former CIA agents Edwin Wilson and Frank Terpil had worked with Muammar Gaddafi, the leader of Libya, to illegally export explosives and train his troops for terrorism.

Shortly before publication, it emerged in the press that Hersh had removed claims at the last minute which were based on forged documents provided to him by fraudster Lex Cusack, including a fake hush money contract between Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe.

He estimated that 15 percent of returning American troops were afflicted with the chronic and multi-symptomatic disorder, and challenged the government claim that they were suffering from war fatigue, as opposed to the effects of a chemical or biological weapon.

Hersh later reported on the government's flawed prosecution of Zacarias Moussaoui, on the U.S.'s aggressive assassination efforts against al-Qaeda members, and on business conflicts of interest held by Richard Perle, chairman of the Pentagon's advisory Defense Policy Board, which led to his resignation.

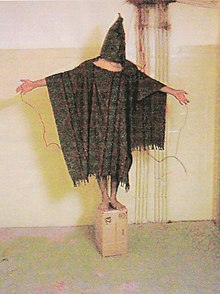

[48] He described these photos: In one, Private [Lynndie] England, a cigarette dangling from her mouth, is giving a jaunty thumbs-up sign and pointing at the genitals of a young Iraqi, who is naked except for a sandbag over his head, as he masturbates.

[50] In two articles in May 2004, "Chain of Command" and "The Gray Zone", Hersh alleged that the abuse stemmed from a top-secret special access program (SAP) authorized by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld during the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, which provided blanket approval for killings, kidnappings, and interrogations (at Guantanamo Bay and CIA black sites) of "high-value" targets.

[51] In a rare statement responding directly to the allegations, Pentagon spokesman Lawrence Di Rita said that they were "outlandish, conspiratorial, and filled with error and anonymous conjecture", and that they reflected "the fevered insights of those with little, if any, connection to the activities in the Department of Defense"; he added that: "With these false claims, the Magazine and the reporter have made themselves part of the story.

[53] In July 2005, an article by Hersh alleged that the U.S. had covertly intervened in favor of Ayad Allawi in the January 2005 Iraqi parliamentary election, in an "off the books" campaign conducted by retired CIA officers and non-government personnel, and with funds "not necessarily" appropriated by Congress.

[54] In a January 2005 article for The New Yorker titled "The Coming Wars", Hersh wrote that the next U.S. target in the Middle East was Iran, and alleged that covert U.S. reconnaissance missions, including a commando task force, had infiltrated the country to gather intelligence on nuclear, chemical, and missile sites since mid-2004.

[54] In a June 2008 article titled "Preparing the Battlefield", Hersh alleged that Congress had secretly appropriated $400 million for a major escalation of covert operations against Iran in late 2007, following a request from President Bush.

[54] In an April 2012 article, Hersh alleged that the U.S. trained members of the Iranian dissident group Mujahideen-e-Khalq (MEK), listed as a "foreign terrorist organization" by the State Department, at a site in Nevada from 2005 to 2007, and had provided intelligence for its assassinations of nuclear scientists.

[70] Blogger Eliot Higgins and chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta disputed some of the claims in the articles with open-source intelligence, writing that the "improvised" rockets had been used by the Syrian Army as early as November 2012, and that the front lines on the day of the attack were just 2 kilometers (1.2 mi) from the impact sites, within Postol's estimated range.

They also criticized the claim of al-Nusra responsibility, citing the high difficulty and expense of producing sarin, and the presence of hexamine in the Ghouta samples, an additive which Syria later declared part of its chemical weapons program.

[73] Higgins again criticized Hersh's claims, writing for Bellingcat that they were inconsistent with Syrian and Russian descriptions of the target and satellite images of the impact sites, as well as findings of sarin and hexamine in samples retrieved by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

[84] Max Fisher of Vox accused Hersh's story of "internal contradictions" and "troubling inconsistencies" in a long article, questioning among other claims that the U.S. and Pakistan had struck a secret deal, as U.S. military aid had fallen and relations had deteriorated in following years.

"[107] In a July 2004 speech to the American Civil Liberties Union, at the height of the Abu Ghraib scandal, Hersh alleged that there existed video tapes of young boys being sexually assaulted at the prison, in which their "shrieking" could be heard.

[107] In his book Chain of Command, however, he clarified that a lawyer in the case had told him about a prisoner witness statement which described the alleged rape of a boy by a foreign contract employee who worked as an interpreter, as a woman was taking pictures.

Although cautioned by Hersh that the information may not be true, Butowsky forwarded the taped call to the Rich family, who were encouraged to hire a private investigator quoted in a later-retracted Fox News article on the alleged FBI report.

[118] Hersh's articles on the Watergate scandal, like those of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, made extensive use of unnamed sources, including deep inside the White House, Justice Department, and Congress.

"[1] Henry Kissinger, in response to Hersh's 1983 book The Price of Power, accused him of including "inference piled on assumption, third-hand hearsay accepted as fact, the self-serving accounts of disgruntled adversaries elevated to gospel, the 'impressions' of people several times removed from the scene.

[124] Hersh's 1997 book The Dark Side of Camelot used very few unnamed sources, but its document hoax controversy and dubious claims drew the criticism of many in the media, with Kennedy biographer Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. calling him "the most gullible investigative reporter perhaps in American history".