Room and pillar mining

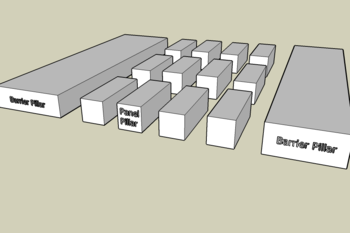

To do this, "rooms" of ore are dug out while "pillars" of untouched material are left to support the roof – overburden.

Calculating the size, shape, and position of pillars is a complicated procedure, and an area of active research.

The room and pillar system is used in mining coal, gypsum,[4] iron,[5] limestone,[6] and uranium[7] ores, particularly when found as manto or blanket deposits, stone and aggregates, talc, soda ash, and potash.

[10] Next, mine layout should be determined, as factors like ventilation, electrical power, and haulage of the ore must be considered[4][10] in cost analysis.

[10] It is desirable to keep the size and shape of rooms and pillars consistent, but some mines strayed from this formula due to lack of planning and deposit characteristics.

[10] Room and pillar mines are developed on a grid basis except where geological features such as faults require the regular pattern to be modified.

This creates a pile of ore that is loaded and hauled out of the mine—the final step of the mining process.

[10] More modern room and pillar mines use a more "continuous" method, that uses machinery to simultaneously grind off rock and move it to the surface.

Once a deposit has been exhausted using this method, the pillars that were left behind initially are removed, or "pulled", retreating back towards the mine's entrance.

[19] The Cargill salt mine 1,700 feet (520 m) below the surface, mostly under Lake Erie at Cleveland, Ohio is similar.

This is due to many factors, including the dangers to miners associated with subsidence, increasing use of other methods with more mechanization, and the decreasing cost of surface mining.

[9] This means that today, room and pillar mining is mostly used for high grade, but small, deep deposits.

In remote areas, collapses can be dangerous to wildlife,[21] but subsidence of abandoned mines can be hazardous to infrastructure above and nearby.