Rosalind Franklin

[9] Moving to Paris in 1947 as a chercheur (postdoctoral researcher) under Jacques Mering at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'État, she became an accomplished X-ray crystallographer.

[20] Her aunt, Helen Caroline Franklin, known in the family as Mamie, was married to Norman de Mattos Bentwich, who was the Attorney General in the British Mandate of Palestine.

[19] Her family was actively involved with the Working Men's College, where her father taught the subjects of electricity, magnetism, and the history of the Great War in the evenings, later becoming the vice principal.

By concluding that substances were expelled in order of molecular size as temperature increased, she helped classify coals and accurately predict their performance for fuel purposes and for production of wartime devices such as gas masks.

At a conference in the autumn of 1946, Weill introduced Franklin to Marcel Mathieu, a director of the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), the network of institutes that comprises the major part of the scientific research laboratories supported by the French government.

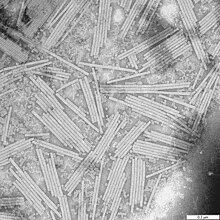

Drawing upon her physical chemistry background, a critical innovation Franklin applied was making the camera chamber that could be controlled for its humidity using different saturated salt solutions.

[75] Franklin was fully committed to experimental data and was sternly against theoretical or model buildings, as she said, "We are not going to speculate, we are going to wait, we are going to let the spots on this photograph tell us what the [DNA] structure is.

[81] In November 1951 James Watson and Francis Crick of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge University had started to build a molecular model of the B-DNA using data similar to that available to both teams at King's.

Photographs of her Birkbeck work table show that Franklin routinely used small molecular models, although certainly not ones on the grand scale successfully used at Cambridge for DNA.

The arrival in Cambridge of Linus Pauling's flawed paper in January 1953 prompted the head of the Cavendish Laboratory, Lawrence Bragg, to encourage Watson and Crick to resume their own model building.

[85][89] Watson and Crick finished building their model on 7 March 1953, a day before they received a letter from Wilkins stating that Franklin was finally leaving and they could put "all hands to the pump".

Further scrutiny of her notebook revealed that Franklin had already thought of the helical structure for B-DNA in February 1953 but was not sure of the number of strands, as she wrote: "Evidence for 2-chain (or 1-chain helix).

[75] Towards the end of February Franklin began to work out the indications of double strands, as she noted: "Structure B does not fit single helical theory, even for low layer-lines."

[94][95] As Franklin considered the double helix, she also realised that the structure would not depend on the detailed order of the bases, and noted that "an infinite variety of nucleotide sequences would be possible to explain the biological specificity of DNA".

[97] Crick and Watson published their model in Nature on 25 April 1953, in an article describing the double-helical structure of DNA with only a footnote acknowledging "having been stimulated by a general knowledge of Franklin and Wilkins' 'unpublished' contribution.

As a result of a deal struck by the two laboratory directors, articles by Wilkins and Franklin, which included their X-ray diffraction data, were modified and then published second and third in the same issue of Nature, seemingly only in support of the Crick and Watson theoretical paper which proposed a model for the B-DNA.

[105] Despite the parting words of Bernal to stop her interest in nucleic acids, Franklin helped Gosling to finish his thesis, although she was no longer his official supervisor.

[107][108] John Finch, a physics student from King's College London, subsequently joined Franklin's group, followed by Kenneth Holmes, a Cambridge graduate, in July 1955.

In 1956, Caspar and Franklin published individual but complementary papers in the 10 March issue of Nature, in which they showed that the RNA in TMV is wound along the inner surface of the hollow virus.

She obtained Bernal's consent in July 1957, though serious concerns were raised after Franklin disclosed her intentions to research live, instead of killed, polio virus at Birkbeck.

William Ginoza of the University of California, Los Angeles, later recalled that Franklin was the opposite of Watson's description of her, and as Maddox comments, Americans enjoyed her "sunny side".

In her later years, Evi Ellis, who had shared her bedroom when a child refugee and who was then married to Ernst Wohlgemuth[29] and had moved to Notting Hill from Chicago, tried matchmaking her with Ralph Miliband but failed.

"[185] Glynn accuses Sayre of erroneously making her sister a feminist heroine,[186] and sees Watson's The Double Helix as the root of what she calls the "Rosalind Industry".

[204] Indeed, after the publication of Watson's The Double Helix exposed Perutz's act, he received so many letters questioning his judgment that he felt the need to both answer them all[205] and to post a general statement in Science excusing himself on the basis of being "inexperienced and casual in administrative matters".

A preliminary version of much of the important material contained in the 1952 December MRC report had been presented by Franklin in a talk she had given in November 1951, which Watson had attended but not understood.

Franklin and Gosling's publication of the DNA X-ray image, in the same issue of Nature, served as the principal evidence:Thus our general ideas are not inconsistent with the model proposed by Watson and Crick in the preceding communication.

[240][241] Aaron Klug, Franklin's colleague and principal beneficiary in her will, was the sole winner of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1982, "for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biologically important nucleic acid-protein complexes".

[310] Narrated by Barbara Flynn, the program features interviews with Wilkins, Gosling, Klug, Maddox,[311] including Franklin's friends Vittorio Luzzati, Caspar, Anne Piper, and Sue Richley.

[315] A play entitled Rosalind: A Question of Life was written by Deborah Gearing to mark the work of Franklin, and was first performed on 1 November 2005 at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre,[316] and published by Oberon Books in 2006.

[320] False Assumptions by Lawrence Aronovitch is a play about the life of Marie Curie in which Franklin is portrayed as frustrated and angry at the lack of recognition for her scientific contributions.