Rose O'Neill

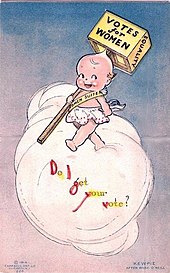

She rose to fame for her creation of the popular comic strip characters, Kewpies, in 1909, and was also the first published female cartoonist in the United States.

Her Kewpie cartoons, which made their debut in a 1909 issue of Ladies' Home Journal, were later manufactured as bisque dolls in 1912 by J. D. Kestner, a German toy company, followed by composition material and celluloid versions.

[3] In 2022 at San Diego Comic-Con, Rose O'Neill was inducted into the Eisner Awards Hall of Fame as a Comic Pioneer.

[8] To market her skills to a broader audience, O'Neill moved to New York in 1893; she stopped in Chicago en route to visit the World Columbian Exposition.

[1][10] While O'Neill was living in New York, her father made a homestead claim on a small tract of land in the Ozarks wilderness of southern Missouri.

[19] A review published by Book News in 1905 considered O'Neill's illustrations to "possess a rare breadth of sympathy with and understanding of humanity".

[19] As educational opportunities were made available in the 19th century, women artists became part of professional enterprises, and some founded their own art associations.

Many women artists, including O'Neill, could be characterized as examples of the educated, modern, and independent "New Woman," a form of gender identity that emerged at the time.

[20][21] According to Prieto, artists "played crucial roles in representing the New Woman, both by drawing images of the icon and exemplifying this emerging type through their own lives".

Other successful illustrators were Jennie Augusta Brownscombe, Jessie Willcox Smith, Elizabeth Shippen Green, and Violet Oakley.

[22] It was amid the New Woman and burgeoning suffragist movements that, in 1908, O'Neill began to concentrate on producing original artwork, and it was during this period that she created the whimsical Kewpie characters for which she became known.

[20] Further publications of the Kewpie comics in Woman's Home Companion and Good Housekeeping helped the cartoon grow in popularity rapidly.

[2][30] The success of the Kewpies amassed her a fortune of $1.4 million,[23] with which she purchased properties including Bonniebrook, an apartment in Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village, Castle Carabas in Connecticut, and Villa Narcissus (bought from Charles Caryl Coleman) on the Isle of Capri, Italy.

[26] While there, she was elected to the Société Coloniale des Artistes Français in 1921, and had exhibitions of her sculptures at the Galerie Devambez in Paris and the Wildenstein Galleries in New York in 1921 and 1922, respectively.

By the 1940s, she had lost the majority of her money and properties, partly through extravagant spending, as well as the cost of fully supporting her family, her entourage of "artistic" hangers-on, and her first husband.

After thirty years of popularity, the Kewpie character phenomenon had faded, and photography was replacing illustration as a commercial vehicle.