Rosetta Stone

It was probably moved in late antiquity or during the Mamluk period, and was eventually used as building material in the construction of Fort Julien near the town of Rashid (Rosetta) in the Nile Delta.

It was the first Ancient Egyptian bilingual text recovered in modern times, and it aroused widespread public interest with its potential to decipher this previously untranslated hieroglyphic script.

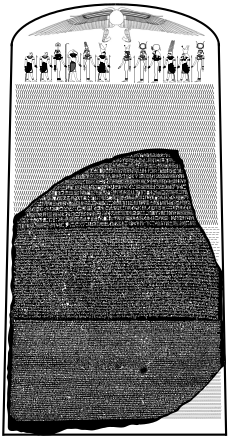

[1] At some period after its arrival in London, the inscriptions were coloured in white chalk to make them more legible, and the remaining surface was covered with a layer of carnauba wax designed to protect it from visitors' fingers.

[3] These additions were removed when the stone was cleaned in 1999, revealing the original dark grey tint of the rock, the sparkle of its crystalline structure, and a pink vein running across the top left corner.

[8][9] The front surface is polished and the inscriptions lightly incised on it; the sides of the stone are smoothed, but the back is only roughly worked, presumably because it would have not been visible when the stele was erected.

The conspirators effectively ruled Egypt as Ptolemy V's guardians[20][21] until a revolt broke out two years later under general Tlepolemus, when Agathoclea and her family were lynched by a mob in Alexandria.

Philip had seized several islands and cities in Caria and Thrace, while the Battle of Panium (198 BC) had resulted in the transfer of Coele-Syria, including Judaea, from the Ptolemies to the Seleucids.

In the preceding Pharaonic period it would have been unheard of for anyone but the divine rulers themselves to make national decisions: by contrast, this way of honouring a king was a feature of Greek cities.

[28] Given that the decree was issued at Memphis, the ancient capital of Egypt, rather than Alexandria, the centre of government of the ruling Ptolemies, it is evident that the young king was anxious to gain their active support.

On 15 July 1799, French soldiers under the command of Colonel d'Hautpoul were strengthening the defences of Fort Julien, a couple of miles north-east of the Egyptian port city of Rosetta (modern-day Rashid).

One of these experts was Jean-Joseph Marcel, a printer and gifted linguist, who is credited as the first to recognise that the middle text was written in the Egyptian demotic script, rarely used for stone inscriptions and seldom seen by scholars at that time, rather than Syriac as had originally been thought.

[42][43] After the surrender, a dispute arose over the fate of the French archaeological and scientific discoveries in Egypt, including the artefacts, biological specimens, notes, plans, and drawings collected by the members of the commission.

Scholars Edward Daniel Clarke and William Richard Hamilton, newly arrived from England, agreed to examine the collections in Alexandria and said they had found many artefacts that the French had not revealed.

[48] New inscriptions painted in white on the left and right edges of the slab stated that it was "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" and "Presented by King George III".

[55] Other than during wartime, the Rosetta Stone has left the British Museum only once: for one month in October 1972, to be displayed alongside Champollion's Lettre at the Louvre in Paris on the 150th anniversary of the letter's publication.

Monumental use of hieroglyphs ceased as temple priesthoods died out and Egypt was converted to Christianity; the last known inscription is dated to 24 August 394, found at Philae and known as the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom.

[63] The discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 provided critical missing information, gradually revealed by a succession of scholars, that eventually allowed Jean-François Champollion to solve the puzzle that Kircher had called the riddle of the Sphinx.

[G] It was reprinted by the Society of Antiquaries in a special issue of its journal Archaeologia in 1811, alongside Weston's previously unpublished English translation, Colonel Turner's narrative, and other documents.

At the time of the stone's discovery, Swedish diplomat and scholar Johan David Åkerblad was working on a little-known script of which some examples had recently been found in Egypt, which came to be known as Demotic.

Champollion saw copies of the brief hieroglyphic and Greek inscriptions of the Philae obelisk in 1822, on which William John Bankes had tentatively noted the names "Ptolemaios" and "Kleopatra" in both languages.

[7] Philippe Derchain and Heinz Josef Thissen have argued that all three versions were composed simultaneously, while Stephen Quirke sees in the decree "an intricate coalescence of three vital textual traditions".

[76] Richard Parkinson points out that the hieroglyphic version strays from archaic formalism and occasionally lapses into language closer to that of the demotic register that the priests more commonly used in everyday life.

[82] He repeated the proposal two years later in Paris, listing the stone as one of several key items belonging to Egypt's cultural heritage, a list which also included: the iconic bust of Nefertiti in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin; a statue of the Great Pyramid architect Hemiunu in the Roemer-und-Pelizaeus-Museum in Hildesheim, Germany; the Dendera Temple Zodiac in the Louvre in Paris; and the bust of Ankhhaf in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

For example, the bilingual Greek-Brahmi coins of the Greco-Bactrian king Agathocles have been described as "little Rosetta stones", allowing Christian Lassen's initial progress towards deciphering the Brahmi script, thus unlocking ancient Indian epigraphy.

[92] The term Rosetta stone has been also used idiomatically to denote the first crucial key in the process of decryption of encoded information, especially when a small but representative sample is recognised as the clue to understanding a larger whole.

[93] Another use of the phrase is found in H. G. Wells's 1933 novel The Shape of Things to Come, where the protagonist finds a manuscript written in shorthand that provides a key to understanding additional scattered material that is sketched out in both longhand and on typewriter.

For example, Nobel laureate Theodor W. Hänsch in a 1979 Scientific American article on spectroscopy wrote that "the spectrum of the hydrogen atoms has proven to be the Rosetta Stone of modern physics: once this pattern of lines had been deciphered much else could also be understood".

[96] The technique of Doppler echocardiography has been called a Rosetta Stone for clinicians trying to understand the complex process by which the left ventricle of the human heart can be filled during various forms of diastolic dysfunction.

[97] The European Space Agency's Rosetta spacecraft, launched to study the comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko in the hope that determining its composition will advance understanding of the origins of the Solar System.

Additionally, "Rosetta", developed and maintained by Canonical (the Ubuntu Linux company) as part of the Launchpad project, is an online language translation tool to help with localisation of software.