Rotavirus

It infects and damages the cells that line the small intestine and causes gastroenteritis (which is often called "stomach flu" despite having no relation to influenza).

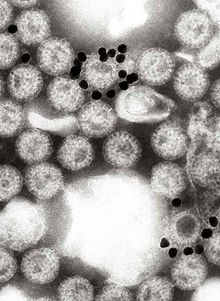

Although rotavirus was discovered in 1973 by Ruth Bishop and her colleagues by electron micrograph images[5] and accounts for approximately one third of hospitalisations for severe diarrhoea in infants and children,[6] its importance has historically been underestimated within the public health community, particularly in developing countries.

[8] Rotaviral enteritis is usually an easily managed disease of childhood, but among children under 5 years of age rotavirus caused an estimated 151,714 deaths from diarrhoea in 2019.

[11][12] Public health campaigns to combat rotavirus focus on providing oral rehydration therapy for infected children and vaccination to prevent the disease.

[25] Because the two genes that determine G-types and P-types can be passed on separately to progeny viruses, different combinations are found.

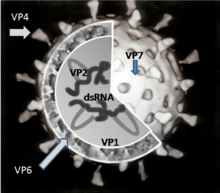

[29] The genome of rotaviruses consists of 11 unique double helix molecules of RNA (dsRNA) which are 18,555 nucleotides in total.

[40] The cap stabilises viral mRNA by protecting it from nucleic acid degrading enzymes called nucleases.

[50] NSP1 also blocks the interferon response, the part of the innate immune system that protects cells from viral infection.

[68] Rotaviral enteritis is a mild to severe disease characterised by nausea, vomiting, watery diarrhoea and low-grade fever.

[76] Rotaviruses replicate mainly in the gut,[77] and infect enterocytes of the villi of the small intestine, leading to structural and functional changes of the epithelium.

The toxic rotavirus protein NSP4 induces age- and calcium ion-dependent chloride secretion, disrupts SGLT1 (sodium/glucose cotransporter 2) transporter-mediated reabsorption of water, apparently reduces activity of brush-border membrane disaccharidases, and activates the calcium ion-dependent secretory reflexes of the enteric nervous system.

[56] The elevated concentrations of calcium ions in the cytosol (which are required for the assembly of the progeny viruses) is achieved by NSP4 acting as a viroporin.

This extracellular form, which is modified by protease enzymes in the gut, is an enterotoxin which acts on uninfected cells via integrin receptors, which in turn cause and increase in intracellular calcium ion concentrations, secretory diarrhoea and autophagy.

[82] The vomiting, which is a characteristic of rotaviral enteritis, is caused by the virus infecting the enterochromaffin cells on the lining of the digestive tract.

[85] A recurrence of mild diarrhoea often follows the reintroduction of milk into the child's diet, due to bacterial fermentation of the disaccharide lactose in the gut.

[88] Maternal trans-placental IgG might play a role in the protection neonates from rotavirus infections, but on the other hand might reduce vaccine efficacy.

[95][96] Specific diagnosis of infection with rotavirus is made by finding the virus in the child's stool by enzyme immunoassay.

[98] Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) can detect and identify all species and serotypes of human rotaviruses.

[100] Depending on the severity of diarrhoea, treatment consists of oral rehydration therapy, during which the child is given extra water to drink that contains specific amounts of salt and sugar.

[101] In 2004, the World Health Organisation (WHO) and UNICEF recommended the use of low-osmolarity oral rehydration solution and zinc supplementation as a two-pronged treatment of acute diarrhoea.

[102] Some infections are serious enough to warrant hospitalisation where fluids are given by intravenous therapy or nasogastric intubation, and the child's electrolytes and blood sugar are monitored.

Because improved sanitation does not decrease the prevalence of rotaviral disease, and the rate of hospitalisations remains high despite the use of oral rehydrating medicines, the primary public health intervention is vaccination.

[115][116] In developing countries in Africa and Asia, where the majority of rotavirus deaths occur, a large number of safety and efficacy trials as well as recent post-introduction impact and effectiveness studies of Rotarix and RotaTeq have found that vaccines dramatically reduced severe disease among infants.

[124] To make rotavirus vaccines available, accessible, and affordable in all countries—particularly low- and middle-income countries in Africa and Asia where the majority of rotavirus deaths occur, PATH (formerly Program for Appropriate Technology in Health), the WHO, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and GAVI have partnered with research institutions and governments to generate and disseminate evidence, lower prices, and accelerate introduction.

[134] Outbreaks of rotavirus A diarrhoea are common among hospitalised infants, young children attending day care centres, and elderly people in nursing homes.

This unusually large and severe outbreak was associated with mutations in the rotavirus A genome, possibly helping the virus escape the prevalent immunity in the population.

[141][142] To date, epidemics caused by rotavirus B have been confined to mainland China, and surveys indicate a lack of immunity to this species in the United States.

[143] Rotavirus C has been associated with rare and sporadic cases of diarrhoea in children, and small outbreaks have occurred in families.

[8] As a pathogen of livestock, notably in young calves and piglets, rotaviruses cause economic loss to farmers because of costs of treatment associated with high morbidity and mortality rates.

[154] These viruses, all causing acute gastroenteritis, were recognised as a collective pathogen affecting humans and other animals worldwide.

- Attachment of the virus to the host cells, which is mediated by VP4 and VP7

- Penetration of the cell by the virus and uncoating of the viral capsid

- Plus strand ssRNA synthesis (this acts as the mRNA) synthesis, which is mediated by VP1, VP3 and VP2

- Formation of the viroplasm, viral RNA packaging and minus strand RNA synthesis and formation of the double-layered virus particles

- Virus particle maturation and release of progeny virions