Royal Alcázar of Madrid

[2]: 7 The building was the central nucleus of the Islamic citadel of Mayrit, a walled district approximately 4 ha (9.9 acres) in size, incorporating not only the castle, but also a mosque and the home of the governor (or emir).

Its steep location near the Altos de Rebeque and overlooking the path of the River Manzanares below was of great strategic importance, being a key factor in the defence of Toledo from frequent Christian incursions into the lands of al-Andalus.

This structure probably followed the progression of similar military constructions in the area—an observation point developed into a small fort—although there is currently a lack of evidence as the place was later quarried for building material by Christians.

After the conquest of Madrid in 1083 by Alfonso VI of León and Castile, the King needed a bigger fortress in order to accommodate his royal court.

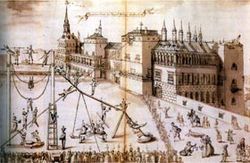

This is evident from seventeenth century engravings and paintings, where medieval-styled semi-circular turrets can be seen on the western side by the Manzanares, in contrast to the architecture of the southern façade.

The Trastámara dynasty turned the Alcázar into its temporary residence, and by the end of the fifteenth century it was one of the main fortresses in the Crown of Castile, as well as the seat of the royal court.

"[citation needed] From this perspective, one can understand the efforts of Charles V to provide the city with a royal residence - the priority of a modern state - or at least, to what it was used to before his arrival in Castile.

The new construction bore the name of the original fortress, the Royal Alcázar of Madrid, despite having lost its military function centuries earlier.

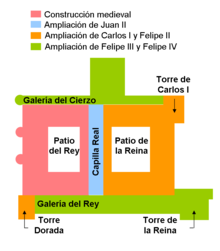

The project was dominated by unmistakable Renaissance features, visible in the main staircase and both the King's and Queen's Courtyards; adorned with archways and supported by columns, allowing light into the building.

Philip II, as prince of Asturias, had shown great interest in the works brought about by his father, the Emperor Charles V, and as king, continued them.

The monarch ordered the refurbishment of his chambers as well as other rooms, and put special effort into their decoration, using tailors, glaziers, carpenters, painters, sculptors and other artisans and artists.

The Golden Tower (la Torre Dorada), whose construction was the most important in this time, was supervised by the architect Juan Bautista de Toledo.

The work, entrusted to the architect Francisco de Mora, involved blending the southern façade with the architectural characteristics of the Golden Tower, as well as redesigning the Queen's rooms.

However, the work to the façade was eventually completed by Juan Gómez de Mora, the preceding architect's nephew, who introduced important innovations to his uncle's design, following the usual Baroque style of the time.

The austere Royal Alcázar was in complete opposition with the French taste he was more familiar with in Versailles, hence his refurbishments' focus on the interior of the palace.

Queen Maria Luisa of Savoy was in charge of the work, assisted by her lady in waiting, Marie Anne de La Trémoille, princess of Ursins.

Some paintings were fixed to the walls, so a large number of those kept in the building (including La Expulsión de los moriscos by Velázquez) were lost.

Fortunately, part of the art collection had previously been moved to the Buen Retiro Palace to protect them during the building work to the Royal Alcázar, which saved them from destruction.

The remaining façades were built from red brick and granite (from Toledo), which gave the building the characteristic colouring of Madrid's traditional architecture.

These materials were abundant in the influential area of the city as clay is plentiful on the banks of the Manzanares and granite in the nearby Sierra de Guadarrama.

The main entrance was on the southern façade, which proved especially problematic in the redesign of the building, due to being dominated by two large square spaces, built in medieval times.

The Royal Alcázar held a huge art collection; it is estimated that at the time of the fire, there were close to 2,000 paintings (both originals and reproductions), of which some 500 were lost.

The approximately 1,000 paintings which were rescued were kept in several buildings after the event, amongst them the San Gil Convent, the Royal Armoury and the homes of the Archbishop of Toledo and the Marquis of Bedmar.

A large part of the art collection had already been moved to the Buen Retiro Palace during the building work carried out on the Alcázar, which saved them from the fire.

Also lost in the fire was another Rubens painting, El rapto de las Sabinas, and the twenty pieces of art that adorned the walls of the Octagonal Room (Pieza Ochavada).

As well as these works, an invaluable collection of work by artists such as (according to the inventories) Tintoretto, Paolo Veronese, Jusepe de Ribera, Hieronymus Bosch, Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Alonso Sánchez Coello, Anthony van Dyck, El Greco, Annibale Carracci, Leonardo da Vinci, Guido Reni, Raphael, Jacopo Bassano, Correggio, and many others.

To the north and west of the Alcázar lay the Picadero plaza and the Gardens (or Orchard) of the Prioress, which connected the palace with the Royal Monastery of the Incarnation.

The work, beginning in 1568 under the reign of Philip II, was initially designed to be an independent construction, but the building became an annex to the Alcázar so as to enable direct communication between them.

The basements, floors and other walls of the building were discovered in the twentieth century during the 1996 redesign of the Plaza de Oriente by the mayor José María Álvarez del Manzano.

The Gardens (or Orchard) of the Prioress were the result of a redesign of the grounds to the north and west of the Royal Alcázar, at the start of the seventeenth century.