Rufus Wilmot Griswold

[8] Griswold moved to Albany, New York, and lived with a 22-year-old flute-playing journalist named George C. Foster, a writer best known for his work New-York by Gas-Light.

[16] His departure on November 27, 1840[17] was by all accounts abrupt, leaving his job with Horace Greeley's New York Tribune, and his library of several thousand volumes.

[18][20] He wrote a long poem in blank verse dedicated to Caroline, titled "Five Days", which was printed in the New York Tribune on November 16, 1842.

[22] Griswold's collection featured poems from over 80 authors,[23] including 17 by Lydia Sigourney, three by Edgar Allan Poe, and 45 by Charles Fenno Hoffman.

[27] Prose Writers of America, published in 1847, was prepared specifically to compete with a similar anthology by Cornelius Mathews and Evert Augustus Duyckinck.

[34] The book is meant to cover events during the presidency of George Washington, though it mixes historical fact with apocryphal legend until one is indistinguishable from the other.

[35] During this period, Griswold occasionally offered his services at the pulpit delivering sermons[36] and he may have received an honorary doctorate from Shurtleff College, a Baptist institution in Illinois, leading to his nickname the "Reverend Dr.

[41] Still, the couple moved together to Charleston, South Carolina, Charlotte's home town, and lived under the same roof, albeit sleeping in separate rooms.

[45] The selections he chose for The Female Poets of America were not necessarily the greatest examples of poetry but instead were chosen because they emphasized traditional morality and values.

[48] In July 1848, he visited poet Sarah Helen Whitman in Providence, Rhode Island, but he had been suffering with vertigo and exhaustion, rarely leaving his apartment at New York University, and was unable to write without taking opium.

[51] Griswold continued editing and contributing literary criticism for various publications, both full-time and freelance, including 22 months from July 1, 1850, to April 1, 1852, with The International Magazine.

[53] In the November 10, 1855, issue of The Criterion, Griswold anonymously reviewed the first edition of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass, declaring: "It is impossible to image how any man's fancy could have conceived such a mass of stupid filth".

Referring to Whitman's poetry, Griswold said he left "this gathering of muck to the laws which ... must have the power to suppress such gross obscenity.

Griswold was the first person in the 19th century to publicly point to and stress the theme of erotic desire and acts between men in Whitman's poetry.

[16] As critic Lewis Gaylord Clark said, it was expected Griswold's book would "become incorporated into the permanent undying literature of our age and nation".

A British editor reviewed the collection and concluded, "with two or three exceptions, there is not a poet of mark in the whole Union" and referred to the anthology as "the most conspicuous act of martyrdom yet committed in the service of the transatlantic muses".

Forgotten, save only by those whom he has injured and insulted, he will sink into oblivion, without leaving a landmark to tell that he once existed; or if he is spoken of hereafter, he will be quoted as the unfaithful servant who abused his trust.

"[32] Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. noted that Griswold researched literature like "a kind of naturalist whose subjects are authors, whose memory is a perfect fauna of all flying and creeping things that feed on ink.

"[28] Evert Augustus Duyckinck commented that "the thought [of a national literature] seems to have entered and taken possession of (Griswold's) mind with the force of monomania".

[85] By the 1850s, Griswold's literary nationalism had subsided somewhat, and he began following the more popular contemporary trend of reading literature from England, France, and Germany.

[84] Publicly, Griswold supported the establishment of international copyright, but he often duplicated entire works during his time as an editor, particularly with The Brother Jonathan.

A contemporary editor said of him: "He takes advantage of a state of things which he declares to be 'immoral, unjust and wicked,' and even while haranguing the loudest, is purloining the fastest.

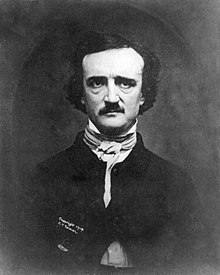

[14] In a letter dated March 29, 1841, Poe sent Griswold several poems for The Poets and Poetry of America anthology, writing that he would be proud to see "one or two of them in the book".

[88] Griswold had expected more praise, and Poe privately told others he was not particularly impressed by the book,[89] even calling it "a most outrageous humbug" in a letter to a friend.

[96] Osgood responded by dedicating a collection of her poetry to Griswold "as a souvenir of admiration for his genius, of regard for his generous character, and of gratitude for his valuable literary counsels".

He claimed that Poe often wandered the streets, either in "madness or melancholy", mumbling and cursing to himself, was easily irritated, was envious of others, and that he "regarded society as composed of villains".

[50] In any case, Griswold, along with James Russell Lowell and Nathaniel Parker Willis, edited a posthumous collection of Poe's works published in three volumes starting in January 1850.

Many elements were fabricated by Griswold using forged letters as evidence and it was denounced by those who knew Poe, including Sarah Helen Whitman, Charles Frederick Briggs, and George Rex Graham.

"[108] Thomas Holley Chivers wrote a book called New Life of Edgar Allan Poe which directly responded to Griswold's accusations.

[109] He said that Griswold "is not only incompetent to Edit any of [Poe's] works, but totally unconscious of the duties which he and every man who sets himself up as a Literary Executor, owe the dead".