Ruminant

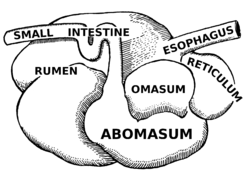

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microbial actions.

The process of rechewing the cud to further break down plant matter and stimulate digestion is called rumination.

[4] Ruminating mammals include cattle, all domesticated and wild bovines, goats, sheep, giraffes, deer, gazelles, and antelopes.

[7] The suborder Ruminantia includes six different families: Tragulidae, Giraffidae, Antilocapridae, Cervidae, Moschidae, and Bovidae.

[8] Ruminantia is a crown group of ruminants within the order Artiodactyla, cladistically defined by Spaulding et al. as "the least inclusive clade that includes Bos taurus (cow) and Tragulus napu (mouse deer)".

[9] Ruminantia's placement within Artiodactyla can be represented in the following cladogram:[10][11][12][13][14] Tylopoda (camels) Suina (pigs) Tragulidae (mouse deer) Pecora (horn bearers) Hippopotamidae (hippopotamuses) Cetacea (whales) Within Ruminantia, the Tragulidae (mouse deer) are considered the most basal family,[15] with the remaining ruminants classified as belonging to the infraorder Pecora.

However, a 2003 phylogenetic study by Alexandre Hassanin (of National Museum of Natural History, France) and colleagues, based on mitochondrial and nuclear analyses, revealed that Moschidae and Bovidae form a clade sister to Cervidae.

[16] The following cladogram is based on a large-scale genome ruminant genome sequence study from 2019:[17] Tragulidae Antilocapridae Giraffidae Cervidae Bovidae Moschidae Hofmann and Stewart divided ruminants into three major categories based on their feed type and feeding habits: concentrate selectors, intermediate types, and grass/roughage eaters, with the assumption that feeding habits in ruminants cause morphological differences in their digestive systems, including salivary glands, rumen size, and rumen papillae.

[5] Monogastric herbivores, such as rhinoceroses, horses, guinea pigs, and rabbits, are not ruminants, as they have a simple single-chambered stomach.

In smaller hindgut fermenters of the order Lagomorpha (rabbits, hares, and pikas), and Caviomorph rodents (Guinea pigs, capybaras, etc.

Saliva is very important because it provides liquid for the microbial population, recirculates nitrogen and minerals, and acts as a buffer for the rumen pH.

Though the rumen and reticulum have different names, they have very similar tissue layers and textures, making it difficult to visually separate them.

[27] Species inhabit a wide range of climates (from tropic to arctic) and habitats (from open plains to forests).

This is compensated for by continuous tooth growth throughout the ruminant's life, as opposed to humans or other nonruminants, whose teeth stop growing after a particular age.

Rumination reduces particle size, which enhances microbial function and allows the digesta to pass more easily through the digestive tract.

Thus, ruminants completely depend on the microbial flora, present in the rumen or hindgut, to digest cellulose.

The hydrolysis of cellulose results in sugars, which are further fermented to acetate, lactate, propionate, butyrate, carbon dioxide, and methane.

As bacteria conduct fermentation in the rumen, they consume about 10% of the carbon, 60% of the phosphorus, and 80% of the nitrogen that the ruminant ingests.

After digesta passes through the rumen, the omasum absorbs excess fluid so that digestive enzymes and acid in the abomasum are not diluted.

Found in the leaf, bud, seed, root, and stem tissues, tannins are widely distributed in many different species of plants.

[36] Tannins can be toxic to ruminants, in that they precipitate proteins, making them unavailable for digestion, and they inhibit the absorption of nutrients by reducing the populations of proteolytic rumen bacteria.

[36] Some ruminants (goats, deer, elk, moose) are able to consume food high in tannins (leaves, twigs, bark) due to the presence in their saliva of tannin-binding proteins.

[42][43] As a by-product of consuming cellulose, cattle belch out methane, there-by returning that carbon sequestered by plants back into the atmosphere.

[48][49] The current U.S. domestic beef and dairy cattle population is around 90 million head, approximately 50% higher than the peak wild population of American bison of 60 million head in the 1700s,[50] which primarily roamed the part of North America that now makes up the United States.