Runaway greenhouse effect

A runaway version of the greenhouse effect can be defined by a limit on a planet's outgoing longwave radiation which is asymptotically reached due to higher surface temperatures evaporating water into the atmosphere, increasing its optical depth.

[4] However, the authors cautioned that "our understanding of the dynamics, thermodynamics, radiative transfer and cloud physics of hot and steamy atmospheres is weak", and that we "cannot therefore completely rule out the possibility that human actions might cause a transition, if not to full runaway, then at least to a much warmer climate state than the present one".

[6] Venus-like conditions on Earth require a large long-term forcing that is unlikely to occur until the sun brightens by some tens of percents, which will take a few billion years.

[7] Earth is expected to experience a runaway greenhouse effect "in about 2 billion years as solar luminosity increases".

[4] While the term was coined by Caltech scientist Andrew Ingersoll in a paper that described a model of the atmosphere of Venus,[9] the initial idea of a limit on terrestrial outgoing infrared radiation was published by George Simpson in 1927.

[10] The physics relevant to the, later-termed, runaway greenhouse effect was explored by Makoto Komabayashi at Nagoya University.

[11] Assuming a water vapor-saturated stratosphere, Komabayashi and Ingersoll independently calculated the limit on outgoing infrared radiation that defines the runaway greenhouse state.

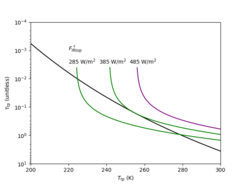

[12] The runaway greenhouse effect is often formulated in terms of how the surface temperature of a planet changes with differing amounts of received starlight.

However, because the Stefan–Boltzmann response mandates that this hotter planet emits more energy, eventually a new radiation balance can be reached and the temperature will be maintained at its new, higher value.

[4] The runaway greenhouse effect can be seen as a limit on a planet's outgoing longwave radiation that, when surpassed, results in a state where water cannot exist in its liquid form (hence, the oceans have all "boiled away").

[9][11] A grey stratosphere (or atmosphere) is an approach to modeling radiative transfer that does not take into account the frequency-dependence of absorption by a gas.

[3][13] Because the model used to derive the Simpson–Nakajima limit (a grey stratosphere in radiative equilibrium and a convecting troposphere) can determine the water concentration as a function of altitude, the model can also be used to determine the surface temperature (or conversely, amount of stellar flux) that results in a high water mixing ratio in the stratosphere.

[13] The concept of a habitable zone has been used by planetary scientists and astrobiologists to define an orbital region around a star in which a planet (or moon) can sustain liquid water.

More accurate calculations have been done using three-dimensional climate models[20] that take into account effects such as planetary rotation and local water mixing ratios as well as cloud feedbacks.

[23][24] Venus is sufficiently strongly heated by the Sun that water vapor can rise much higher in the atmosphere and be split into hydrogen and oxygen by ultraviolet light.

[29][30] Climate scientist John Houghton wrote in 2005 that "[there] is no possibility of [Venus's] runaway greenhouse conditions occurring on the Earth".

[31] However, climatologist James Hansen stated in Storms of My Grandchildren (2009) that burning coal and mining oil sands will result in runaway greenhouse on Earth.

[32] A re-evaluation in 2013 of the effect of water vapor in the climate models showed that James Hansen's outcome would require ten times the amount of CO2 we could release from burning all the oil, coal, and natural gas in Earth's crust.

[36] Most scientists believe that a runaway greenhouse effect is inevitable in the long term, as the Sun gradually becomes more luminous as it ages, and will spell the end of all life on Earth.

[37] This is due to the colder upper layer of the troposphere acting as a cold trap currently preventing Earth from permanently losing its water to space at present, even with manmade global warming (this is also the reason why climate change is only going to make extreme weather events worse in the near term, as a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture, as even with global warming, the cold trap ensures that the current atmosphere will still be too cold to allow water vapor to be rapidly lost to space).

However, the rate is gradually accelerating, as the sun gets warmer, to perhaps as fast as one millimeter every 1000 years, by ultimately making the atmosphere so hot that the cold trap is pushed even higher up until it eventually fails to prevent the water from being lost to space.

[37] Ward and Brownlee predict that there will be two variations of the future warming feedback: the "moist greenhouse" in which water vapor dominates the troposphere and starts to accumulate in the stratosphere and the "runaway greenhouse" in which water vapor becomes a dominant component of the atmosphere such that the Earth starts to undergo rapid warming, which could send its surface temperature to over 900 °C (1,650 °F), causing its entire surface to melt and killing all life, perhaps about three billion years from now.

In both cases, the moist and runaway greenhouse states the loss of oceans will turn the Earth into a primarily-desert world.

The only water left on the planet would be in a few evaporating ponds scattered near the poles as well as huge salt flats around what was once the ocean floor, much like the Atacama Desert in Chile or Badwater Basin in Death Valley.

Through this effect, a runaway feedback process may have removed much carbon dioxide and water vapor from the atmosphere and cooled the planet.

This means that as a planet's temperature decreases and more of its water freezes, its ability to absorb light is reduced, which in turn makes it even colder, creating a positive feedback loop.

[40] This effect, combined with the decrease in heat-retaining clouds and vapor, becomes runaway once snow and ice coverage reach a certain threshold (within 30 degrees of the equator), plunging the planet into a stable snowball state.