Russel Wright

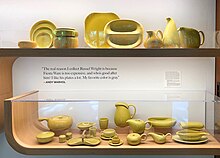

His best-selling ceramic dinnerware was credited with encouraging the general public to enjoy creative modern design at table with his many other ranges of furniture, accessories, and textiles.

[citation needed] Working outward from there, he designed tableware to larger furniture, architecture to landscaping, all fostering an easy, informal lifestyle.

The couple also wrote the best-selling Guide to Easier Living in 1950, which described how to reduce housework and increase leisure time through efficient design and household management.

One of the patterns of "Flair", called "Ming Lace" has the actual leaves of the Chinese jade orchid tree tinted and embedded inside the translucent plastic.

As with his ceramic dinnerware, Wright began designing his Melmac only in solid colors, but by the end of the 1950s created several patterns ornamented with decoration, usually depicting plant forms.

[citation needed] Wright left Princeton for the New York City theater world and quickly became a set designer for Norman Bel Geddes.

This early association with the theater led to further work with George Cukor, Lee Simonson, Robert Edmond Jones, and Rouben Mamoulian.

Upon returning to New York City, he started his own design firm making theatrical props and small decorative cast metal objects.

[12] After his wife's death, Russel Wright retired to his 75-acre (300,000 m2) estate, Manitoga in Garrison, New York, building an eco-sensitive Modernist home and studio called Dragon Rock surrounded by extensive woodland gardens.

The "Russel Wright Papers" from 1931–1965 are held in an archive at Syracuse University Library Special Collections Research Center, containing 60 feet (18 m) of architectural drawings, photographs, manuscripts, models and ephemera.