Russian language in Ukraine

[citation needed] The first new waves of Russian settlers onto what is now Ukrainian territory came in the late-16th century to the empty lands of Slobozhanshchyna[7] (in the region of Kharkiv) that Russia had gained from the Tatars,[8] or from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania[citation needed] - although Ukrainian peasants from the Polish-Lithuanian west escaping harsh exploitative conditions outnumbered them.

[9] More Russian speakers appeared in the northern, central and eastern territories of modern Ukraine during the late-17th century, following the Cossack Rebellion (1648–1657) which Bohdan Khmelnytsky led against Poland.

[citation needed] Following the Pereyaslav Rada of 1654 the northern and eastern parts of present-day Ukraine came under the hegemony of the Russian Tsardom.

This brought the first significant, but still small, wave of Russian settlers into central Ukraine (primarily several thousand soldiers stationed in garrisons,[11][need quotation to verify] out of a population of approximately 1.2 million[12] non-Russians).

Beginning in the late 18th century, large numbers of Russians (as well as of Armenians, Bulgarians, Greeks and of other Christians and Jews) settled in newly acquired lands in what is now southern Ukraine, a region then known as Novorossiya ("New Russia").

These lands – previously known as the Wild Fields – had been sparsely populated prior to the 18th century due to the threat of Crimean-Tatar raids, but once Saint Petersburg had eliminated the Tatar state as a threat, Russian nobles were granted large tracts of fertile land for working by newly arrived peasants, most of them ethnic Ukrainians but many of them Russians.

[citation needed] At the beginning of the 20th century the Russians formed the largest ethnic group in almost all large cities within Ukraine's modern borders, including Kyiv (54.2%), Kharkiv (63.1%), Odesa (49.09%), Mykolaiv (66.33%), Mariupol (63.22%), Luhansk, (68.16%), Kherson (47.21%), Melitopol (42.8%), Ekaterinoslav, (41.78%), Kropyvnytskyi (34.64%), Simferopol (45.64%), Yalta (66.17%), Kerch (57.8%), Sevastopol (63.46%).

[16] In 1881 the decree was amended by Alexander III to allow the publishing of lyrics and dictionaries, and the performances of some plays in the Ukrainian language with local officials' approval.

In February 2017, the Ukrainian government banned the commercial importation of books from Russia, which had accounted for up to 60% of all titles sold in Ukraine.

[25] The law does state that persons belonging to the indigenous peoples of Ukraine are guaranteed the right to study at public pre-school institutes and primary schools in "the language of instruction of the respective indigenous people, along with the state language of instruction" in separate classes or groups.[25][relevant?]

The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe (PACE) has expressed concern with this measure and with the lack of "real consultation" with the representatives of national minorities.

[26] In July 2018, The Mykolaiv Okrug Administrative Court liquidated the status of Russian as a regional language, on the suit (bringing to the norms of the national legislation due to the recognition of the law "On the principles of the state language policy" by the Constitutional Court of Ukraine as unconstitutional) of the First Deputy Prosecutor of the Mykolaiv Oblast.

[27] In October and December 2018, parliaments of the city of Kherson and of Kharkiv Oblast also abolished the status of the Russian language as a regional one.

According to official data from the 2001 Ukrainian census, the Russian language was native for 29.6% of Ukraine's population (about 14.3 million people).

[35] 8% stated they had experienced difficulty in the execution (understanding) of official documents; mostly middle-aged and elderly people in South Ukraine and the Donbas.

His clipping service spread an announcement of his promise to make Russian language proficiency obligatory for officials who interact with Russian-speaking citizens.

In February 2017 the Ukrainian government completely banned the commercial importation of books from Russia, which had accounted for up to 60% of all titles sold.

[65] A survey conducted in February 2015 by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology found that support for Russian as a state language had dropped to 19% (37% in the south, 31% in Donbas and other eastern oblasts).

On the other hand, before the war, almost a quarter of Ukrainians were in favour of granting Russian the status of the state language, while today only 7% support it.

[70][71] According to a poll carried out by the Social Research Center at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in late 2009 ideological issues were ranked third (15%) as reasons to organize mass protest actions (in particular, the issues of joining NATO, the status of the Russian language, the activities of left- and right-wing political groups, etc.

Nikolai Gogol is probably the most famous example of shared Russo-Ukrainian heritage: Ukrainian by descent, he wrote in Russian, and significantly contributed to culture of both nations.

A number of notable Russian writers and poets hailed from Odesa, including Ilya Ilf and Yevgeny Petrov, Anna Akhmatova, Isaak Babel.

Other Russophone Ukrainian writers of sci-fi and fantasy include Vladimir Vasilyev, Vladislav Rusanov, Alexander Mazin and Fyodor Berezin.

[84][85] Since 19 August 2014 Ukraine has blocked 14 Russian television channels "to protect its media space from aggression from Russia, which has been deliberately inciting hatred and discord among Ukrainian citizens".

On May 15, 2017, Ukrainian president Poroshenko issued a decree that demanded all Ukrainian internet providers to block access to all most popular Russian social media and websites, including VK, Odnoklassniki, Mail.ru, Yandex citing matters of national security in the context of the war in Donbas and explaining it as a response to "massive Russian cyberattacks across the world".

[93][94] On the following day the demand for applications that allowed to access blocked websites skyrocketed in Ukrainian segments of App Store and Google Play.

[95] The ban was condemned by Human Rights Watch that called it "a cynical, politically expedient attack on the right to information affecting millions of Ukrainians, and their personal and professional lives",[96] while head of Council of Europe[97][better source needed] expressed a "strong concern" about the ban.

The Law on Education formerly granted Ukrainian families (parents and their children) a right to choose their native language for schools and studies.

[1] Advanced technical and engineering courses at the university level in Ukraine were taught in Russian, which was changed according to the 2017 law "On Education".

According to a survey of the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology in December of 2022, 58 percent of Ukrainians considered the Russian language "unimportant".

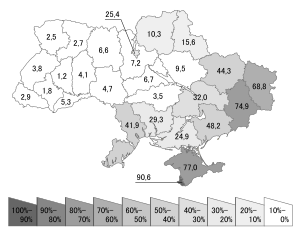

(according to 2001 census )