French invasion of Russia

At the Council at Fili Kutuzov made the critical decision not to defend the city but to orchestrate a general withdrawal, prioritizing the preservation of the Russian army.

[28] Due to favorable weather conditions, Napoleon delayed his retreat and, hoping to secure supplies, began a different route westward than the one the army had devastated on the way there.

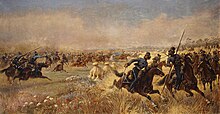

Shortages of food and winter attire for the soldiers and provision for the horses, combined with guerilla warfare from Russian peasants and Cossacks, resulted in significant losses.

While exact figures remain elusive due to the absence of meticulous records,[31] estimations varied and often included exaggerated counts, overlooking auxiliary troops.

Napoleon, rising to power in 1799 and assuming autocratic rule over France, orchestrated numerous military campaigns that led to the establishment of the first French empire.

[47] In an attempt to secure greater cooperation from Russia, Napoleon initially pursued an alliance by proposing marriage to Anna Pavlovna, the youngest sister of Alexander.

This second Polish war will be as glorious for the French arms as the first has been, but the peace we shall conclude shall carry with it its own guarantee, and will terminate the fatal influence which Russia for fifty years past has exercised in Europe.

Extensive magazines were strategically set up in towns and cities across Poland and East Prussia,[57] while the Vistula river valley was developed into a vital supply base in 1811–1812.

[68] Breslau, Plock and Wyszogród were turned into grain depots, milling vast quantities of flour for delivery to Thorn, where 60,000 biscuits were produced every day.

[70] The standard heavy wagons, well-suited for the dense and partially paved road networks of Germany and France, proved too cumbersome for the sparse and primitive Russian dirt tracks, further damaged by the unstable weather.

[64]The heavy losses to disease, hunger and desertion in the early months of the campaign were in large part due to the inability to transport provisions quickly enough to the troops.

[73] Other accounts describe eating the flesh of horses still walking, too cold to react in pain; drinking blood and preparing black pudding was popular.

[65] A Lieutenant Mertens—a Württemberger serving with Ney's III Corps—reported in his diary that oppressive heat followed by cold nights and rain left them with dead horses and camping in swamp-like conditions with dysentery and fever raging through the ranks with hundreds in a field hospital that had to be set up for the purpose.

[65] Rapid forced marches quickly caused desertion, suicide and starvation, and exposed the troops to filthy water and disease, while the logistics trains lost horses by the thousands, further exacerbating the problems.

[136] Jakob Walter describes his foraging experience during Russia's scorched earth tactics:Finally we arrived at Polotsk, a large city on the other side of the Western Dvina River.

The next day Tsar Alexander signed a document that Kutuzov was promoted General Field Marshal, the highest military rank of the Imperial Russian Army.

Russian sources suggest Kutuzov wrote a number of orders and letters to Rostopchin, the Moscow military governor, about saving the city or the army.

31 August] 1812, the main forces of Kutuzov departed from the village, now Golitsyno and camped near Odintsovo, 20 km to the west, followed by Mortier and Joachim Murat's vanguard.

[165] On 19 September Murat lost sight of Kutuzov who changed direction and turned west to Podolsk and Tarutino where he would be more protected by the surrounding hills and the Nara river.

[169]Kutuzov's food supplies and reinforcements were mostly coming up through Kaluga from the fertile and populous southern provinces, his new deployment gave him every opportunity to feed his men and horses and rebuild their strength.

Lacking clear direction or adequate supplies, the army began its retreat from the region, facing the prospect of even worse disasters ahead.

The Battle of Maloyaroslavets, a testament to Kutuzov's strategic acumen, forced the French Army to retrace its steps along the Old Smolensk road, reversing their previous eastward advance.

[184]Russian forces also seized control of the French supply depots at Polotsk, Vitebsk and Minsk, dealing a severe blow to Napoleon's already faltering campaign.

[185] Despite this reinforcement, as all French corps advanced towards Borisov, they encountered another critical obstacle: the strategic bridge needed to cross the Berezina River had been destroyed by the Russian army.

Minard's map shows that the opposite is true as the French losses were highest in the summer and autumn, due to inadequate preparation of logistics resulting in insufficient supplies, while many troops were also killed by disease.

The French deficiencies in equipment caused by the assumption that their campaign would be concluded before the cold weather set in were a large factor in the number of casualties they suffered.

On 24 June 1812, around 400,000–500,000 men of the Grande Armée, the largest army assembled up to that point in European history, crossed the border into Russia and headed towards Moscow.

[22] Minard's famous infographic (see below) depicts the march ingeniously by showing the size of the advancing army, overlaid on a rough map, as well as the retreating soldiers together with temperatures recorded (as much as 30 below zero on the Réaumur scale (−38 °C, −36 °F)) on their return.

[205] Sweden, Russia's only ally, did not send supporting troops, but the alliance made it possible to withdraw the 45,000-man Russian corps Steinheil from Finland and use it in the later battles (20,000 men were sent to Riga and Polotsk).

The poor roads and harsh environment took a deadly toll on both horses and men, while politically Russia's oppressed serfs remained, for the most part, loyal to the aristocracy.