Russian entry into World War I

[1][2] The Ottoman Empire subsequently joined the Central Powers by conducting the Black Sea Raid and engaged in warfare against Russia along their shared border at the Caucasus.

[3] Historians studying the causes of World War I have often highlighted the roles of Germany and Austria-Hungary, while downplaying Russia's contribution to the outbreak of this global conflict.

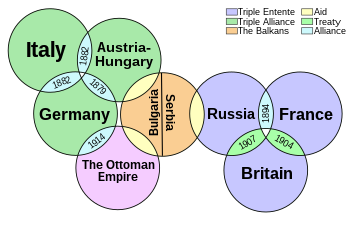

The prevailing scholarly view has focused on Russia's defense of Orthodox Serbia, its pan-Slavic aspirations, its treaty commitments with France, and its efforts to maintain its status as a major world power.

However, historian Sean McMeekin emphasizes Russia's ambitions to expand its empire southward and to capture Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as a gateway to the Mediterranean Sea.

[4] Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austria-Hungarian throne, was assassinated by Bosnian Serbs on June 28, 1914, in response to Austria-Hungary's annexation of the predominantly Slavic province.

Although Austria-Hungary could not conclusively prove that the Serbian state had sponsored the assassination, it issued an ultimatum to Serbia during the July Crisis one month later, expecting it to be rejected and thus leading to war.

While Russia had no formal treaty obligation to Serbia, it emphasized its interest in controlling the Balkans, viewing it as a long-term strategic goal to gain a military advantage over Germany and Austria-Hungary.

However, Russia had secured French support and feared that a failure to defend Serbia would damage its credibility, constituting a significant political setback in its Balkan ambitions.

[7] The proximity raised the risk of conflict between the two powers, compounded by Russia's longstanding goal of gaining control of the Bosporus Straits, which would provide access to the Mediterranean Sea dominated by Britain.

In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed the former Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, leading to the Russian-backed formation of the Balkan League aimed at preventing further Austrian expansion.

Tsar Nicholas II made all final decisions but often received conflicting advice from his advisors, leading to flawed decision-making throughout his reign.

British historian David Stevenson, for instance, highlights the "disastrous consequences of deficient civil-military liaison," where civilians and generals lacked communication.

The Foreign Minister had to warn Nicholas that "unless he yielded to the popular demand and took up arms in support of Serbia, he would risk facing revolution and losing his throne.

Its socialists were more estranged from the existing order than those elsewhere in Europe, and a strike wave among the industrial workforce reached a crescendo with the general stoppage in St. Petersburg in July 1914.

[11]French ambassador Maurice Paléologue quickly gained influence by repeatedly pledging that France would go to war alongside Russia, aligning with President Raymond Poincaré's position.

While the General Staff possessed expertise, it was often overshadowed by the elite Imperial Guards, a favored stronghold of the aristocracy that prioritized ceremonial parades over strategic military planning.

Historians debate whether Paléologue exceeded his instructions, but there is consensus that he failed to provide Paris with precise information, neglecting to warn that Russian mobilization could precipitate a world war.

[14][15][16] On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, triggering a period of indecision for Tsar Nicholas II regarding Russia's course of action.

In a series of letters exchanged with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany (the so-called "Willy–Nicky correspondence"), both cousins expressed their desire for peace and attempted to persuade the other to relent.

In response to the discovery of Russian partial mobilization, which had been ordered on July 25, Germany announced a state of pre-mobilization, citing the imminent threat of war.

With the Baltic Sea blocked by German U-boats and surface ships, and the Dardanelles obstructed by the guns of Germany's ally, the Ottoman Empire, Russia initially could only receive assistance through Arkhangelsk, which was frozen solid in winter, or Vladivostok, over 6,400 kilometers (4,000 mi) from the front line.

In September 1914, to alleviate pressure on France, the Russians were compelled to halt a successful offensive against Austria-Hungary in Galicia and instead attack German-held Silesia.

[32] Gradually, a war of attrition took hold on the expansive Eastern Front, with the Russians confronting the combined forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary, leading to staggering losses.

The scholarly consensus minimizes the mention of Russia, with only brief references to its defense of Serbia, its Pan-Slavic activities, its treaty commitments with France, and its efforts to maintain its status as a major power.