Russian military deception

The doctrine has also been put into practice in peacetime, with denial and deception operations in events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Prague Spring, and the annexation of Crimea.

[7] Early in Russia's history, in the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380, Prince Dmitry Donskoy defeated the armies of the Mongol Golden Horde using a surprise attack from a regiment hidden in forest.

The 1924 Soviet directive for higher commands stated that operational deception had to be "based upon the principles of activity, naturalness, diversity, and continuity and includes secrecy, imitation, demonstrative actions, and disinformation.

It largely repeats the 1944 Encyclopedia's concept, but adds that[12] Strategic maskirovka is carried out at national and theater levels to mislead the enemy as to political and military capabilities, intentions and timing of actions.

[21] The meaning evolved in Soviet practice and doctrine to include strategic, political, and diplomatic objectives, in other words operating at all levels.

[3] According to the analyst James Hansen, deception "is treated as an operational art to be polished by professors of military science and officers who specialize in this area.

"[22] In 2015, Julian Lindley-French described strategic maskirovka as "a new level of ambition"[23] established by Moscow to unbalance the West both politically and militarily.

[31] An article in The Moscow Times explained: "But маскировка has a broader military meaning: strategic, operational, physical and tactical deception.

It is the whole shebang—from guys in ski masks or uniforms with no insignia, to undercover activities, to hidden weapons transfers, to—well, starting a civil war but pretending that you've done nothing of the sort.

Finally, Smith identified principles—plausibility, continuity through peace and war, variety, and persistent aggressive activity; and contributing factors, namely technological capability and political strategy.

The deceptions included apparent requests for material for bunkers, the broadcasting of the noise of pile-drivers and wide distribution of a pamphlet What the Soviet Soldier Must Know in Defence.

The Russians claimed that surprise had been achieved; this is confirmed by the fact that German intelligence failed to notice Zhukov's concentration of 20th and 31st Armies on Rzhev.

[36] Military deception based on secrecy was critical in hiding Soviet preparations for the decisive Operation Uranus encirclement in the Battle of Stalingrad.

[37][29][38] In the historian Paul Adair's view, the successful November 1942 Soviet counter-attack at Stalingrad was the first instance of Stavka's newly discovered confidence in large-scale deception.

[41] To the south of Stalingrad, for the southern arm of the pincer movement, 160,000 men with 550 guns, 430 tanks and 14,000 trucks were ferried across the much larger River Volga, which was beginning to freeze over with dangerous ice floes, entirely at night.

[42] Despite the correct appreciation by German air reconnaissance of a major build-up of forces on the River Don,[43] the commander of the 6th Army, Friedrich Paulus took no action.

[45] Deception was put into practice on a large scale in the 1943 Battle of Kursk, especially on the Red Army's Steppe Front commanded by Ivan Konev.

The Soviet forces were moved into position at night and carefully concealed, as were the extensively prepared defences-in-depth, with multiple lines of defence, minefields, and as many as 200 anti-tank guns per mile.

[51] Glantz records that the German general Friedrich von Mellenthin wrote[52] The horrible counter-attacks, in which huge masses of manpower and equipment took part, were an unpleasant surprise for us ...

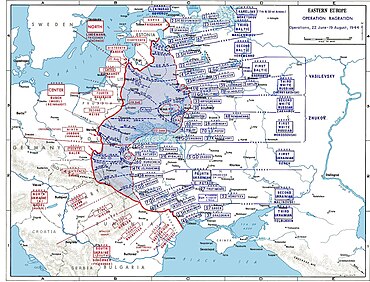

[55] Stavka succeeded in concealing the size and position of very large movements of supplies, as well as of forces including seven armies, eleven aviation corps and over 200,000 troop replacements.

[61] Hitler's own reckless optimism and determination to hold on to captured territory at all costs encouraged him to believe the picture suggested by the Russians.

[63] Anadyr was planned from the start with elaborate denial and deception, ranging from the soldiers' ski boots and fleece-lined parkas to the name of the operation, a river and town in the chilly far east.

[22] In Hansen's view, the fact that the Killian Report[65] did not even mention adversarial denial and deception was an indication that American intelligence had not begun to study foreign D&D; it did not do so for another 20 years.

Hansen considered it likely that with a properly-prepared "deception-aware analytic corps", America could have seen through Khrushchev's plan long before Maj. Heyser's revealing U-2 mission.

[66] When the Kremlin had failed to reverse the Czechoslovak leader Alexander Dubček's liberal reforms with threats, it decided to use force, masked by deception.

The measures taken included transferring fuel and ammunition out of Czechoslovakia on a supposed logistics exercise; and confining most of their soldiers to barracks across the northern Warsaw Pact area.

The Czechoslovak authorities thus did not suspect anything when two Aeroflot airliners made unscheduled landings at night, full of "fit young men".

[66] Reinforcements were then brought in by road, in complete radio silence, leaving NATO electronic warfare units "confused and frustrated".

As the BBC writer, Lucy Ash put it: "Five weeks later, once the annexation had been rubber-stamped by the Parliament in Moscow, Putin admitted Russian troops had been deployed in Crimea after all.

[72] Russia sent "humanitarian" convoys to Donbas; the first, of military trucks painted white, attracted much media attention, and was described as "a wonderful example of maskirovka" by a US Air Force General.