Rydberg atom

Thus, Rydberg atoms are extremely large, with loosely bound valence electrons, easily perturbed or ionized by collisions or external fields.

The existence of the Rydberg series was first demonstrated in 1885 when Johann Balmer discovered a simple empirical formula for the wavelengths of light associated with transitions in atomic hydrogen.

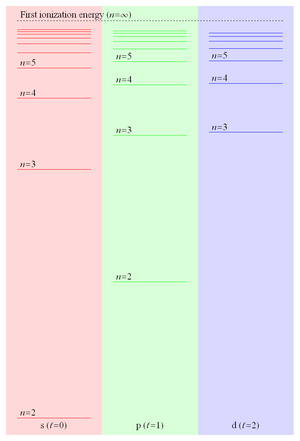

This formula indicated the existence of an infinite series of ever more closely spaced discrete energy levels converging on a finite limit.

[6] This series was qualitatively explained in 1913 by Niels Bohr with his semiclassical model of the hydrogen atom in which quantized values of angular momentum lead to the observed discrete energy levels.

The arrival of tunable dye lasers in the 1970s allowed a much greater level of control over populations of excited atoms.

In optical excitation, the incident photon is absorbed by the target atom, resulting in a precise final state energy.

The problem of producing single state, mono-energetic populations of Rydberg atoms thus becomes the somewhat simpler problem of precisely controlling the frequency of the laser output, This form of direct optical excitation is generally limited to experiments with the alkali metals, because the ground state binding energy in other species is generally too high to be accessible with most laser systems.

The narrow spacing between adjacent n-levels in the Rydberg series means that states can approach degeneracy even for relatively modest field strengths.

The presence of additional terms in the potential energy can lead to coupling resulting in avoided crossings as shown for lithium in figure 6.

[18] The large sizes and low binding energies of Rydberg atoms lead to a high magnetic susceptibility,

Rydberg atoms’ large sizes and susceptibility to perturbation and ionisation by electric and magnetic fields, are an important factor determining the properties of plasmas.

[23] Rydberg atoms occur in space due to the dynamic equilibrium between photoionization by hot stars and recombination with electrons, which at these very low densities usually proceeds via the electron re-joining the atom in a very high n state, and then gradually dropping through the energy levels to the ground state, giving rise to a sequence of recombination spectral lines spread across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Improved theoretical analysis showed that this effect had been overestimated, although collisional broadening does eventually limit detectability of the lines at very high n.[25] The record wavelength for hydrogen is λ = 73 cm for H253α, implying atomic diameters of a few microns, and for carbon, λ = 18 metres, from C732α,[26] from atoms with a diameter of 57 micron.

Because all astrophysical Rydberg atoms are hydrogenic, the frequencies of transitions for H, He, and C are given by the same formula, except for the slightly different reduced mass of the valence electron for each element.

[30] Since RRLs are numerous and weak, common practice is to average the velocity spectra of several neighbouring lines, to improve sensitivity.

Coherent control of these interactions combined with their relatively long lifetime makes them a suitable candidate to realize a quantum computer.

[33][34] Strongly interacting Rydberg atoms also feature quantum critical behavior, which makes them interesting to study on their own.

[49][50] High electric dipole moments between Rydberg atomic states are used for radio frequency and terahertz sensing and imaging,[51][52] including non-demolition measurements of individual microwave photons.

[56][57] In October 2018, the United States Army Research Laboratory publicly discussed efforts to develop a super wideband radio receiver using Rydberg atoms.

[58] In March 2020, the laboratory announced that its scientists analysed the Rydberg sensor's sensitivity to oscillating electric fields over an enormous range of frequencies—from 0 to 1012 Hertz (the spectrum to 0.3mm wavelength).

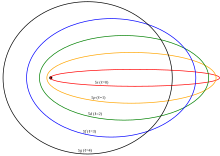

The resulting trajectory becomes progressively more distorted over time, eventually going through the full range of angular momentum from L = LMAX, to a straight line L = 0, to the initial orbit in the opposite sense