Atomic orbital

They are derived from description by early spectroscopists of certain series of alkali metal spectroscopic lines as sharp, principal, diffuse, and fundamental.

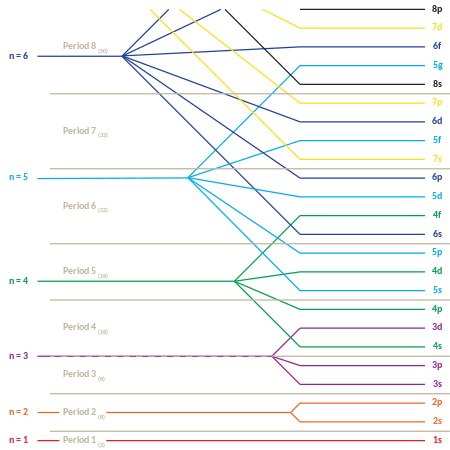

The repeating periodicity of blocks of 2, 6, 10, and 14 elements within sections of periodic table arises naturally from total number of electrons that occupy a complete set of s, p, d, and f orbitals, respectively, though for higher values of quantum number n, particularly when the atom bears a positive charge, energies of certain sub-shells become very similar and so, order in which they are said to be populated by electrons (e.g., Cr = [Ar]4s13d5 and Cr2+ = [Ar]3d4) can be rationalized only somewhat arbitrarily.

An analogy might be that of a large and often oddly shaped "atmosphere" (the electron), distributed around a relatively tiny planet (the nucleus).

functions as real combinations of spherical harmonics Yℓm(θ, φ) (where ℓ and m are quantum numbers).

There are typically three mathematical forms for the radial functions R(r) which can be chosen as a starting point for the calculation of the properties of atoms and molecules with many electrons: Although hydrogen-like orbitals are still used as pedagogical tools, the advent of computers has made STOs preferable for atoms and diatomic molecules since combinations of STOs can replace the nodes in hydrogen-like orbitals.

In 1909, Ernest Rutherford discovered that the bulk of the atomic mass was tightly condensed into a nucleus, which was also found to be positively charged.

In 1913, Rutherford's post-doctoral student, Niels Bohr, proposed a new model of the atom, wherein electrons orbited the nucleus with classical periods, but were permitted to have only discrete values of angular momentum, quantized in units ħ.

The significance of the Bohr model was that it related the lines in emission and absorption spectra to the energy differences between the orbits that electrons could take around an atom.

In chemistry, Erwin Schrödinger, Linus Pauling, Mulliken and others noted that the consequence of Heisenberg's relation was that the electron, as a wave packet, could not be considered to have an exact location in its orbital.

In the Schrödinger equation for this system of one negative and one positive particle, the atomic orbitals are the eigenstates of the Hamiltonian operator for the energy.

They can be obtained analytically, meaning that the resulting orbitals are products of a polynomial series, and exponential and trigonometric functions.

The rules restricting the values of the quantum numbers, and their energies (see below), explain the electron configuration of the atoms and the periodic table.

These quantum numbers occur only in certain combinations of values, and their physical interpretation changes depending on whether real or complex versions of the atomic orbitals are employed.

The azimuthal quantum number ℓ describes the orbital angular momentum of each electron and is a non-negative integer.

It determines the magnitude of the current circulating around that axis and the orbital contribution to the magnetic moment of an electron via the Ampèrian loop model.

The higher nuclear charge Z of heavier elements causes their orbitals to contract by comparison to lighter ones, so that the size of the atom remains very roughly constant, even as the number of electrons increases.

Recently, there has been an effort to experimentally image the 1s and 2p orbitals in a SrTiO3 crystal using scanning transmission electron microscopy with energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy.

[32] Because the imaging was conducted using an electron beam, Coulombic beam-orbital interaction that is often termed as the impact parameter effect is included in the outcome (see the figure at right).

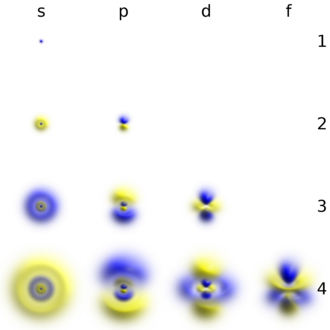

See comparison in the following picture: The shapes of atomic orbitals can be qualitatively understood by considering the analogous case of standing waves on a circular drum.

If this displacement is taken as being analogous to the probability of finding an electron at a given distance from the nucleus, then it will be seen that the many modes of the vibrating disk form patterns that trace the various shapes of atomic orbitals.

The basic reason for this correspondence lies in the fact that the distribution of kinetic energy and momentum in a matter-wave is predictive of where the particle associated with the wave will be.

This antinode means the electron is most likely to be at the physical position of the nucleus (which it passes straight through without scattering or striking it), since it is moving (on average) most rapidly at that point, giving it maximal momentum.

Below, a number of drum membrane vibration modes and the respective wave functions of the hydrogen atom are shown.

The increase in energy for subshells of increasing angular momentum in larger atoms is due to electron–electron interaction effects, and it is specifically related to the ability of low angular momentum electrons to penetrate more effectively toward the nucleus, where they are subject to less screening from the charge of intervening electrons.

The result is a compressed periodic table, with each entry representing two successive elements: Although this is the general order of orbital filling according to the Madelung rule, there are exceptions, and the actual electronic energies of each element are also dependent upon additional details of the atoms (see Electron configuration § Atoms: Aufbau principle and Madelung rule).

Examples of significant physical outcomes of this effect include the lowered melting temperature of mercury (which results from 6s electrons not being available for metal bonding) and the golden color of gold and caesium.

The critical Z value, which makes the atom unstable with regard to high-field breakdown of the vacuum and production of electron-positron pairs, does not occur until Z is about 173.

These conditions are not seen except transiently in collisions of very heavy nuclei such as lead or uranium in accelerators, where such electron-positron production from these effects has been claimed to be observed.

[39] In late period 8 elements, a hybrid of 8p3/2 and 9p1/2 is expected to exist,[40] where "3/2" and "1/2" refer to the total angular momentum quantum number.

This "pp" hybrid may be responsible for the p-block of the period due to properties similar to p subshells in ordinary valence shells.