S-50 (Manhattan Project)

The liquid thermal diffusion process was not one of the enrichment technologies initially selected for use in the Manhattan Project, and was developed independently by Philip H. Abelson and other scientists at the United States Naval Research Laboratory.

Pilot plants were built at the Anacostia Naval Air Station and the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and a production facility at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The S-50 plant ceased production in September 1945, but it was reopened in May 1946, and used by the United States Army Air Forces Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project.

[1] Fears that a German atomic bomb project would develop nuclear weapons, especially among scientists who were refugees from Nazi Germany and other fascist countries, were expressed in the Einstein-Szilard letter.

[4] Niels Bohr and John Archibald Wheeler applied the liquid drop model of the atomic nucleus to explain the mechanism of nuclear fission.

[7] At the University of Birmingham in Britain, the Australian physicist Mark Oliphant assigned two refugee physicists—Frisch and Rudolf Peierls—the task of investigating the feasibility of an atomic bomb, ironically because their status as enemy aliens precluded their working on secret projects like radar.

[18] He was among the first American scientists to verify nuclear fission,[19] reporting his results in an article submitted to the Physical Review in February 1939,[20] and collaborated with Edwin McMillan on the discovery of neptunium.

In July 1940, Ross Gunn from the United States Naval Research Laboratory (NRL) showed him a 1939 paper on the subject by Harold Urey, and Abelson became intrigued by the possibility of using the liquid thermal diffusion process.

The NRL agreed to make $2,500 available to the Carnegie Institution to allow Abelson to continue his work, and in October 1940, Briggs arranged for it to be moved to the Bureau of Standards, where there were better facilities.

In early 1942, the NDRC awarded Harshaw a contract to build a pilot plant to produce 10 pounds (4.5 kg) of uranium hexafluoride per day.

[23] Groves visited the pilot plant again on 10 December 1942, this time with Warren K. Lewis, a professor of chemical engineering from MIT, and three DuPont employees.

[31] It considered Lewis' report, and passed on its recommendation to Vannevar Bush, the director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD), of which the S-1 Executive Committee was a part.

[33] James B. Conant, the chairman of the NDRC and the S-1 Executive Committee, was concerned that the navy was running its own nuclear project, but Bush felt that it did no harm.

Liquid thermal diffusion was a viable means of producing enriched uranium, and all he needed was details about nuclear reactor design, which he knew was being pursued by the Metallurgical Laboratory in Chicago.

Bush was unwilling to provide the requested data, but arranged with Rear Admiral William R. Purnell, a fellow member of the Military Policy Committee that ran the Manhattan Project, for Abelson's efforts to receive additional support.

[32] The following week, Briggs, Urey, and Eger V. Murphree from the S-1 Executive Committee, along with Karl Cohen and W. I. Thompson from Standard Oil, visited the pilot plant at Anacostia.

They calculated that a liquid thermal diffusion plant capable of producing 1 kg per day of uranium enriched to 90% uranium-235 would require 21,800 36-foot (11 m) columns, each with a separation factor of 30.7%.

This included 1,700 short tons (1,500 t) of scarce copper for the outer tubes and nickel for the inner, which would be required to resist corrosion by the steam and uranium hexafluoride respectively.

[34][35] Between February and July 1943 the Anacostia pilot plant produced 236 pounds (107 kg) of slightly enriched uranium hexafluoride, which was shipped to the Metallurgical Laboratory.

[38] The Philadelphia pilot plant occupied 13,000 square feet (1,200 m2) of space on a site one block west of Broad Street, near the Delaware River.

[35] Groves therefore asked Murphree on 12 June for a costing of a production plant capable of producing 50 kg of uranium enriched to between 0.9 and 3.0 percent uranium-235 per day.

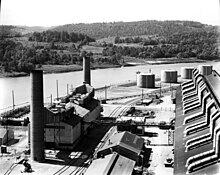

[35] Sites at Watts Bar Dam, Muscle Shoals and Detroit were considered, but it was decided to build it at the Clinton Engineer Works, where water could be obtained from the Clinch River and steam from the K-25 powerhouse.

[15] An S-50 Division was created at the Manhattan District headquarters in June under Lieutenant Colonel Mark C. Fox, with Major Thomas J. Evans, Jr., as his assistant with special authority for plant construction.

Groves selected the H. K. Ferguson Company of Cleveland, Ohio, as the prime construction contractor on its record of finishing jobs on time,[50] notably the Gulf Ordnance Plant in Mississippi,[51] on a cost plus fixed fee contract.

In August 1944, Groves, Conant and Fox asked ten enlisted men of the Special Engineer Detachment (SED) at Oak Ridge for volunteers, warning that the job would be dangerous.

[54] On 2 September 1944, SED Private Arnold Kramish, and two civilians, Peter N. Bragg, Jr., an NRL chemical engineer, and Douglas P. Meigs, a Fercleve employee, were working in a transfer room when a 600-pound (270 kg) cylinder of uranium hexafluoride exploded, rupturing nearby steam pipes.

[60] Colonel Stafford L. Warren, the chief of the Manhattan District's Medical Section, removed the internal organs of the dead and sent them back to Oak Ridge for analysis.

"[45] Soon after the war ended in August 1945, Lieutenant Colonel Arthur V. Peterson,[64] the Manhattan District officer with overall responsibility for the production of fissile material,[65] recommended that the S-50 plant be placed on stand-by.

[42] Starting May 1946, the S-50 plant buildings were utilised, not as a production facility, but by the United States Army Air Forces' Nuclear Energy for the Propulsion of Aircraft (NEPA) project.

[66] NEPA operated until May 1951, when it was superseded by the joint Atomic Energy Commission-United States Air Force Aircraft Nuclear Propulsion project.