s-process

In the s-process, a seed nucleus undergoes neutron capture to form an isotope with one higher atomic mass.

A range of elements and isotopes can be produced by the s-process, because of the intervention of alpha decay steps along the reaction chain.

The relative abundances of elements and isotopes produced depends on the source of the neutrons and how their flux changes over time.

Each branch of the s-process reaction chain eventually terminates at a cycle involving lead, bismuth, and polonium.

The s-process contrasts with the r-process, in which successive neutron captures are rapid: they happen more quickly than the beta decay can occur.

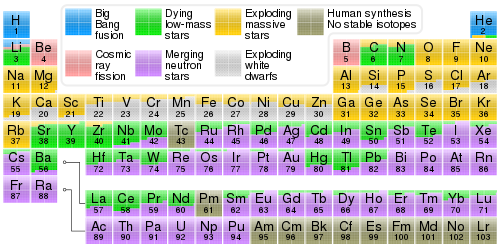

The r-process dominates in environments with higher fluxes of free neutrons; it produces heavier elements and more neutron-rich isotopes than the s-process.

[1] Among other things, these data showed abundance peaks for strontium, barium, and lead, which, according to quantum mechanics and the nuclear shell model, are particularly stable nuclei, much like the noble gases are chemically inert.

In a particularly illustrative case, the element technetium, whose longest half-life is 4.2 million years, had been discovered in s-, M-, and N-type stars in 1952[3][4] by Paul W.

It also showed that no one single value for neutron flux could account for the observed s-process abundances, but that a wide range is required.

Important series of measurements of neutron-capture cross sections were reported from Oak Ridge National Lab in 1965[14] and by Karlsruhe Nuclear Physics Center in 1982[15] and subsequently, these placed the s-process on the firm quantitative basis that it enjoys today.

The extent to which the s-process moves up the elements in the chart of isotopes to higher mass numbers is essentially determined by the degree to which the star in question is able to produce neutrons.

Bismuth is actually slightly radioactive, but with a half-life so long—a billion times the present age of the universe—that it is effectively stable over the lifetime of any existing star.