SHA-1

[15][9][4] In February 2017, CWI Amsterdam and Google announced they had performed a collision attack against SHA-1, publishing two dissimilar PDF files which produced the same SHA-1 hash.

It was withdrawn by the NSA shortly after publication and was superseded by the revised version, published in 1995 in FIPS PUB 180-1 and commonly designated SHA-1.

SHA-1 forms part of several widely used security applications and protocols, including TLS and SSL, PGP, SSH, S/MIME, and IPsec.

Thus the strength of a hash function is usually compared to a symmetric cipher of half the message digest length.

[28] Due to the block and iterative structure of the algorithms and the absence of additional final steps, all SHA functions (except SHA-3)[29] are vulnerable to length-extension and partial-message collision attacks.

At CRYPTO 98, two French researchers, Florent Chabaud and Antoine Joux, presented an attack on SHA-0: collisions can be found with complexity 261, fewer than the 280 for an ideal hash function of the same size.

Finding the collision had complexity 251 and took about 80,000 processor-hours on a supercomputer with 256 Itanium 2 processors (equivalent to 13 days of full-time use of the computer).

On 17 August 2004, at the Rump Session of CRYPTO 2004, preliminary results were announced by Wang, Feng, Lai, and Yu, about an attack on MD5, SHA-0 and other hash functions.

[37] In early 2005, Vincent Rijmen and Elisabeth Oswald published an attack on a reduced version of SHA-1 – 53 out of 80 rounds – which finds collisions with a computational effort of fewer than 280 operations.

In an interview, Yin states that, "Roughly, we exploit the following two weaknesses: One is that the file preprocessing step is not complicated enough; another is that certain math operations in the first 20 rounds have unexpected security problems.

[41] Christophe De Cannière and Christian Rechberger further improved the attack on SHA-1 in "Finding SHA-1 Characteristics: General Results and Applications,"[42] receiving the Best Paper Award at ASIACRYPT 2006.

[44] In order to find an actual collision in the full 80 rounds of the hash function, however, tremendous amounts of computer time are required.

To that end, a collision search for SHA-1 using the volunteer computing platform BOINC began August 8, 2007, organized by the Graz University of Technology.

[46][47] In 2008, an attack methodology by Stéphane Manuel reported hash collisions with an estimated theoretical complexity of 251 to 257 operations.

[49] Cameron McDonald, Philip Hawkes and Josef Pieprzyk presented a hash collision attack with claimed complexity 252 at the Rump Session of Eurocrypt 2009.

[50] However, the accompanying paper, "Differential Path for SHA-1 with complexity O(252)" has been withdrawn due to the authors' discovery that their estimate was incorrect.

[51] One attack against SHA-1 was Marc Stevens[52] with an estimated cost of $2.77M (2012) to break a single hash value by renting CPU power from cloud servers.

On 8 October 2015, Marc Stevens, Pierre Karpman, and Thomas Peyrin published a freestart collision attack on SHA-1's compression function that requires only 257 SHA-1 evaluations.

This does not directly translate into a collision on the full SHA-1 hash function (where an attacker is not able to freely choose the initial internal state), but undermines the security claims for SHA-1.

[10] The method was based on their earlier work, as well as the auxiliary paths (or boomerangs) speed-up technique from Joux and Peyrin, and using high performance/cost efficient GPU cards from Nvidia.

[10] On 23 February 2017, the CWI (Centrum Wiskunde & Informatica) and Google announced the SHAttered attack, in which they generated two different PDF files with the same SHA-1 hash in roughly 263.1 SHA-1 evaluations.

[2] On 24 April 2019 a paper by Gaëtan Leurent and Thomas Peyrin presented at Eurocrypt 2019 described an enhancement to the previously best chosen-prefix attack in Merkle–Damgård–like digest functions based on Davies–Meyer block ciphers.

The chosen constant values used in the algorithm were assumed to be nothing up my sleeve numbers: Instead of the formulation from the original FIPS PUB 180-1 shown, the following equivalent expressions may be used to compute f in the main loop above: It was also shown[57] that for the rounds 32–79 the computation of: can be replaced with: This transformation keeps all operands 64-bit aligned and, by removing the dependency of w[i] on w[i-3], allows efficient SIMD implementation with a vector length of 4 like x86 SSE instructions.

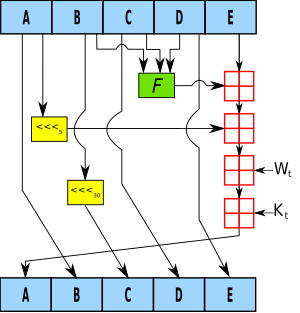

- A, B, C, D and E are 32-bit words of the state;

- F is a nonlinear function that varies;

- denotes a left bit rotation by n places;

- n varies for each operation;

- W t is the expanded message word of round t ;

- K t is the round constant of round t ;

-

denotes addition modulo 2

32

.

denotes addition modulo 2

32

.