Sacred geometry

These and other correspondences are sometimes interpreted in terms of sacred geometry and considered to be further proof of the natural significance of geometric forms.

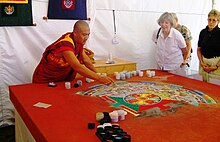

Indian and Himalayan spiritual communities often constructed temples and fortifications on design plans of mandala and yantra.

Many of the sacred geometry principles of the human body and of ancient architecture were compiled into the Vitruvian Man drawing by Leonardo da Vinci.

This is epitomized in feng shui, which are architectural principles outlining the design plans of buildings in order to optimize the harmony of man and nature through the movement of Chi, or “life-generating energy.” [8] In order to maximize the flow of Chi throughout a building, its design plan must utilize specific shapes.

[8] The Forbidden City is an example of a building that uses sacred geometry through the principles of feng shui in its design plan.

The Hall of Supreme Harmony, which was the Emperor’s throne room, is located at the midpoint or “epicenter” of the central axis.

These may constitute the entire decoration, may form a framework for floral or calligraphic embellishments, or may retreat into the background around other motifs.

Geometric patterns occur in a variety of forms in Islamic art and architecture including kilim carpets, Persian girih and Moroccan/Algerian zellige tilework, muqarnas decorative vaulting, jali pierced stone screens, ceramics, leather, stained glass, woodwork, and metalwork.

The Agamas are a collection of Sanskrit,[10] Tamil, and Grantha[11] scriptures chiefly constituting the methods of temple construction and creation of idols, worship means of deities, philosophical doctrines, meditative practices, attainment of sixfold desires, and four kinds of yoga.

[10] Elaborate rules are laid out in the Agamas for Shilpa (the art of sculpture) describing the quality requirements of such matters as the places where temples are to be built, the kinds of image to be installed, the materials from which they are to be made, their dimensions, proportions, air circulation, and lighting in the temple complex.

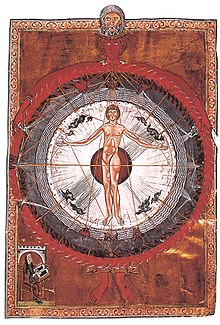

[15] In the High Middle Ages, leading Christian philosophers explained the layout of the universe in terms of a microcosm analogy.

In her book describing the divine visions she witnessed, Hildegard of Bingen explains that she saw an outstretched human figure located within a circular orb.

[16] When interpreted by theologians, the human figure was Christ and mankind showing the Earthly realm and the circumference of the circle was a representation of the universe.

[17] He further creates a cosmic order of circular forms that stretches from Jerusalem in the Earthly realm up to God in Heaven.

If the geometric diagram does not intersect major physical points in the image, the result is what Skinner calls "unanchored geometry".