Sacrifice

In individual non-Christian ethnic religions, terms translated as "sacrifice" include the Indic yajna, the Greek thusia, the Germanic blōtan, the Semitic qorban/qurban, Slavic żertwa, etc.

But the word sacrifice also occurs in metaphorical use to describe doing good for others or taking a short-term loss in return for a greater power gain, such as in a game of chess.

It also served a social or economic function in those cultures where the edible portions of the animal were distributed among those attending the sacrifice for consumption.

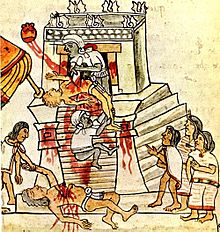

Animal sacrifice has turned up in almost all cultures, from the Hebrews to the Greeks and Romans (particularly the purifying ceremony Lustratio), Egyptians (for example in the cult of Apis) and from the Aztecs to the Yoruba.

[10] Some of these sacrifices were to help the sun rise, some to help the rains come, and some to dedicate the expansions of the great Templo Mayor, located in the heart of Tenochtitlán (the capital of the Aztec Empire).

In Scandinavia, the old Scandinavian religion contained human sacrifice, as both the Norse sagas and German historians relate.

In the Aeneid by Virgil, the character Sinon claims (falsely) that he was going to be a human sacrifice to Poseidon to calm the seas.

Human sacrifice is no longer officially condoned in any country,[11] and any cases which may take place are regarded as murder.

Sacrificing to ancestors was an important duty of nobles, and an emperor could hold hunts, start wars, and convene royal family members in order to get the resources to hold sacrifices, [12] serving to unify states in a common goal and demonstrate the strength of the emperor's rule.

Archaeologist Kwang-chih Chang states in his book Art, Myth and Ritual: the Path to Political Authority in Ancient China (1983) that the sacrificial system strengthened the authority of ancient China's ruling class and promoted production, e.g. through casting ritual bronzes.

Confucius supported the restoration of the Zhou sacrificial system, which excluded human sacrifice, with the goal of maintaining social order and enlightening people.

Members of Chinese folk religions often use pork, chicken, duck, fish, squid, or shrimp in sacrificial offerings.

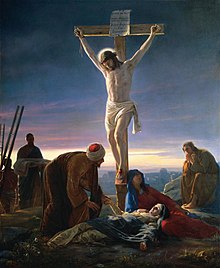

The complete identification of the Mass with the sacrifice of the cross is found in Christ's words at the last supper over the bread and wine: "This is my body, which is given up for you," and "This is my blood of the new covenant, which is shed...unto the forgiveness of sins."

The bread and wine, offered by Melchizedek in sacrifice in the old covenant (Genesis 14:18; Psalm 110:4), are transformed through the Mass into the body and blood of Christ (see transubstantiation; note: the Orthodox Church and Methodist Church do not hold as dogma, as do Catholics, the doctrine of transubstantiation, preferring rather to not make an assertion regarding the "how" of the sacraments),[17][18] and the offering becomes one with that of Christ on the cross.

Through the Mass, the effects of the one sacrifice of the cross can be understood as working toward the redemption of those present, for their specific intentions and prayers, and to assisting the souls in purgatory.

In this way, the celebration of Holy Communion causes the partakers to repeatedly envision the sacrificial death of the Lord, which enables them to proclaim it with conviction (1 Corinthians 11: 26).

But at the same time, in the mystery of the Church as his Body, Christ has in a sense opened his own redemptive suffering to all human suffering" (Salvifici Doloris 19; 24).Some Christians reject the idea of the Eucharist as a sacrifice, inclining to see it as merely a holy meal (even if they believe in a form of the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine, as Reformed Christians do).

The Roman Catholic response is that the sacrifice of the Mass in the New Covenant is that one sacrifice for sins on the cross which transcends time offered in an unbloody manner, as discussed above, and that Christ is the real priest at every Mass working through mere human beings to whom he has granted the grace of a share in his priesthood.

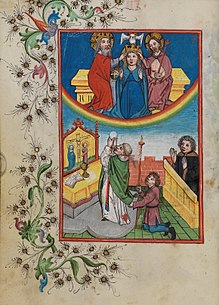

The Orthodox also see the Eucharistic Liturgy as a bloodless sacrifice, during which the bread and wine we offer to God become the Body and Blood of Jesus Christ through the descent and operation of the Holy Spirit, Who effects the change."

This view is witnessed to by the prayers of the Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom, when the priest says: "Accept, O God, our supplications, make us to be worthy to offer unto thee supplications and prayers and bloodless sacrifices for all thy people," and "Remembering this saving commandment and all those things which came to pass for us: the cross, the grave, the resurrection on the third day, the ascension into heaven, the sitting down at the right hand, the second and glorious coming again, Thine own of Thine own we offer unto Thee on behalf of all and for all," and "… Thou didst become man and didst take the name of our High Priest, and deliver unto us the priestly rite of this liturgical and bloodless sacrifice…" The modern practice of Hindu animal sacrifice is mostly associated with Shaktism, and in currents of folk Hinduism strongly rooted in local popular or tribal traditions.

On the occasion of Eid ul Adha (Festival of Sacrifice), affluent Muslims all over the world perform the Sunnah of Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) by sacrificing a cow or sheep.

But, in precise non-secular nomenclature, the word was later confined to the sacrifice of associate animal slaughtered for the sake of Allah.

[24] A similar symbology, which is a reflection of Abraham and Ismael's dilemma, is the stoning of the Jamaraat which takes place during the pilgrimage.

[26] Maimonides, a medieval Jewish rationalist, argued that God always held sacrifice inferior to prayer and philosophical meditation.

In the Guide for the Perplexed, he writes: In contrast, many others such as Nachmanides (in his Torah commentary on Leviticus 1:9) disagreed, contending that sacrifices are an ideal in Judaism, completely central.

The teachings of the Torah and Tanakh reveal the Israelites's familiarity with human sacrifices, as exemplified by the near-sacrifice of Isaac by his father Abraham (Genesis 22:1–24) and some believe, the actual sacrifice of Jephthah's daughter (Judges 11:31–40), while many believe that Jephthah's daughter was committed for life in service equivalent to a nunnery of the day, as indicated by her lament over her "weep for my virginity" and never having known a man (v37).

The king of Moab gives his firstborn son and heir as a whole burnt offering, albeit to the pagan god Chemosh.