Safavid occupation of Basra

The Safavid attempts to retake Basra in 1624, 1625, and 1628–1629 proved unsuccessful, through a combination of Imperial Portuguese interference, pressing concerns on other fronts and, finally, Shah Abbas the Great's (r. 1588–1629) death.

In 1697, members of the Musha'sha' loyal to Farajollah Khan, the Safavid-appointed governor of Safavid Arabestan, defeated Shaykh Mane and his men, ousting them from the city.

The Safavid government realized that Shaykh Mane and his men were keen to retake Basra and wanted to attack nearby Hoveyzeh, the capital of Arabestan Province.

Basra was of particular geopolitical importance in the 16th and 17th centuries, being on the border between the rival (Sunni) Ottoman and (Shi'i) Safavid empires, on the frontier of the Arabian Desert, and having a pivotal role in the growth of the Indian Ocean trade.

Although the two empires claimed jurisdiction over the city at various times, their authority was nominal for the most part, with de facto control being in the hands of local governors who ruled under Safavid or Ottoman suzerainty.

[1][2] During this period, large parts of present-day Iraq were made unsafe by the depredations of the semi-nomadic and "fiercely independent" Arabs in the south and Kurds in the north, who attacked passing caravans.

[3] From 1436 to 1508 de facto control was in the hands of the Musha'sha', a tribal confederation of radical Shi'ites found mainly on the edges of the marshes at the border of the Safavid province of Arabestan (present-day Khuzestan).

[3] Twelve years later, during the Ottoman–Safavid War of 1532–1555, the ruler of Basra, Rashid ibn Mughamis, acknowledged the Ottoman sultan Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) as his suzerain, who in turn confirmed him as governor of the city.

As the modern historian Rudi Matthee explains, The area was difficult to defend, cut off as it was from the central Persian plateau by the Zagros mountain range.

The flat semi-desert land was inhospitable terrain for Qizilbash warriors used to the high plains and mountains of the Persian heartland and eastern Anatolia.

Their preference for guerilla tactics, the ambush and the quick dash followed by retreat into the mountains, as opposed to open confrontation on the battlefield did not serve them well in Iraq with its alluvial flatlands and swamps.

The Safavid attempts in 1624, 1625, and 1628–1629 during the War of 1623–1639 proved unsuccessful, through a combination of Portuguese interference, pressing concerns on other fronts and, finally, Abbas' death.

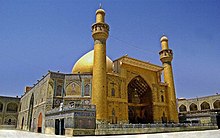

[2] Unlike most of his predecessors, Soltan Hoseyn actively encouraged pilgrims to visit the Shi'ite holy shrines in Iraq, which they did in unprecedented numbers.

[9] The Safavid-appointed vali ("viceroy", "governor") of neighbouring Arabestan province, Farajollah Khan, was also concerned about the links between the Musha'sha' and Shaykh Mane.

[2][9] Farajollah Khan and his loyal Musha'sha' emerged victorious and captured Basra in name of the Safavid Shah, prompting Shaykh Mane to flee.

[2][9] When the Safavids realized that Shaykh Mane and his tribesmen were keen to retake Basra,[b] and even wanted to attack Hoveyzeh, the provincial capital of Arabestan Province, Shah Soltan Hoseyn issued a farman (a decree), ordering an army from the Safavid province of Lorestan led by Ali Mardan Khan, chief of the Fayli tribe and the governor of Kohgiluyeh, to move on Basra.

[2] The activities of the Kurdish rebel Suleiman Baba, who had captured the town of Ardalan and the fortress of Urmia near the Ottoman border in the same year, reinforced their concerns.

[10] In late 1697, Shaykh Mane, having made peace with his former enemy Farajollah Khan,[c] and assisted by Musha'sha' defectors, defeated a large Safavid force near the fortress of Khurma (Khorma) and captured their general.

[10] According to resident Carmelites (members of a Roman Catholic mendicant order) in Basra the city prospered under the beneficent rule of these two Safavid governors, while according to the Scottish sea captain Alexander Hamilton the Iranians encouraged trade and were kind to foreign merchants, unlike the Turks.