Saint-Charles shaft

In the second half of the nineteenth century, this shaft made it possible to mine large coal seams, contributing to the company's golden age.

After closure, the pit buildings were converted into housing; the slag heaps were re-used between the wars, as they were still rich in coal.

At the end of the twentieth century, these same slag heaps, which had become a dumping ground for a nearby factory, burst into flames, frightening the local population.

In 1843, Charles Demandre and Joseph Bezanson bought the Ronchamp concession and continued sinking shaft no.

7 shaft was commissioned, borehole X was drilled on the Champagney plain, uncovering significant coal seams.

[4] In 1848, a steam engine consisting of a single vertical cylinder with a diameter of 49 centimeters and a stroke of 1.356 meters was installed.

It therefore decided to sink an inclined plane at the same time as the Saint-Joseph shaft, to reach the area to be mined more quickly.

[11] A cleat machine has already been installed at the bottom of Compagnie des Mines d'Anzin's Davy pit in La Sentinelle, in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais coalfield, and the collieries have decided to use the same system at Ronchamp.

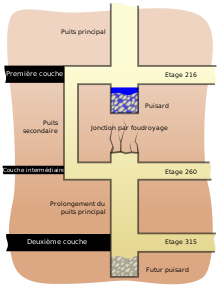

[12] In 1850, more than 200 meters below the surface, a steam engine and two boilers were installed in a large room close to the coal beds.

The underground machines and boilers were supplied by Sthelier of Thann, as were the engine and all the cleat equipment for the vertical shaft.

Conversely, engineer Francois Mathet, who joined the company in 1855, was highly critical of the system and its adoption, finding it dangerous for miners' lives due to the drought that could disrupt ventilation and even cause firedamp.

[13] On October 19, the underground boilers were lit, but immediately the fire, fanned by the 250-meter-high chimney, sucked all the air out of the mine.

It too suffered numerous breakdowns, requiring frequent shutdowns to readjust various parts over several months and in the years that followed.

Finally, on March 29, 1857, the Board of Directors decided to return to the cable extraction system, and the vertical cleat machine was dismantled in 48 days, starting the following May 17.

The management lodged a complaint for coalition offenses, but the Haute-Saône prefecture ruled in favor of the miners, and the engineer was sentenced to prison for flagrant breaches of safety.

On January 18 the following year, a dog and a lighted lamp descended to the bottom of the shaft to test for the presence of a firedamp.

[6] After the 1886 disaster, a large part of the galleries and the construction site were destroyed, in addition, forty years of intensive mining had greatly depleted the deposit, leaving the shaft virtually abandoned.

But three years later, strong demand for coal prompted the company to rehabilitate the entire site and resume mining.

[17] In 1891, the pit was fitted out to accommodate around a hundred workers, but two years later, work was again halted, and only water was brought up from the shaft.

[18] The following year, mining was resumed to remove the remains of coal panels,[notes 2] estimated to weigh 10,000 tonnes.

The store was run by the company, and miners' purchases were deducted directly from their wages via their order and payroll books.

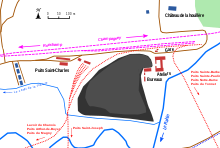

[20]To accommodate the large workforce employed at the Saint-Charles shaft, a mining housing estate was built in 1872, a few dozen meters from the pithead.

It consisted of four houses built of roughcast sandstone rubble, each with a single storey and long-sloped mechanical tile roofs.

[24] The “terril du puits Saint-Charles” is a fairly extensive flat slag heap where waste rock has been piling up for half a century.

A neighboring plant (MagLum) had previously buried waste such as zinc, cyanide, nickel, sulfur, polyurethane foam, hydrogen sulfide, phenols and hydrocarbon derivatives there.

Thick black smoke billowed over the communes of Ronchamp and Champagney, causing concern and mobilizing the population.

Gas analyses and health monitoring of children were carried out (27 of them complained of various symptoms: vomiting, nausea, headaches, throat and eye irritations).

Analyses revealed heavy metal content (including aluminum) 750 times higher than the norm, as well as traces of trichloroethylene and nitrate vapors.