Saint-Domingue

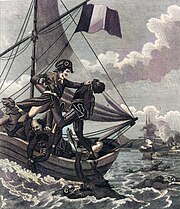

[3] The slave rebellion later allied with Republican French forces following the abolition of slavery in the colony in 1793, although this alienated the island's dominant slave-owning class.

Although the Spanish destroyed the buccaneers' settlements several times, on each occasion they returned, drawn by the abundance of natural resources: hardwood trees, wild hogs and cattle, and fresh water.

Nicknamed the "Pearl of the Antilles," Saint-Domingue became the richest and most prosperous French colony in the West Indies, cementing its status as an important port in the Americas for goods and products flowing to and from France and Europe.

On 22 July 1795, Spain ceded to France the remaining Spanish part of the island of Hispaniola, Santo Domingo (now the Dominican Republic), in the second Treaty of Basel, ending the War of the Pyrenees.

As in New Orleans, a system of plaçage developed, in which white men had a kind of common-law marriage with slave or free mistresses, and provided for them with a dowry, sometimes freedom, and often education or apprenticeships for their children.

The Gens de couleur libres class was made up of affranchis (ex-slaves), free-born blacks, and mixed-race people, and they controlled much wealth and land in the same way as petits blancs; they held full citizenship and civil equality with other French subjects.

Starting in the early 1760s, and gaining much impetus after 1769, Bourbon royalist authorities began attempts to cut Creoles of color out of Saint-Domingue's society, banning them from working in positions of public trust or as respected professionals.

Statutes forbade Gens de couleur from taking up certain professions, wearing European clothing, carrying swords or firearms in public, or attending social functions where whites were present.

This was the last region of the colony to be settled, owing to its distance from Atlantic shipping lanes and its formidable terrain, with the highest mountain range in the Caribbean.

Some slaves became skilled workmen, and they received privileges such as better food, the ability to go into town, and liberté des savanes (savannah liberty), a sort of freedom with certain rules.

Their time was chiefly spent in eating wangoo (boiled Indian cornflour), fish, land-crabs, and yams; sleeping; beating the African drum, composed of a barrel covered with a goat's skin; dancing, quarrelling, and love-making after their own peculiar amusement.

[22] Despite a rural police, due to Saint-Domingue's rough terrain and isolation away from French administration, the Code Noir's protections were sometimes ignored on remote sugar plantations.

Justin Girod-Chantrans, a famous contemporary French traveler and naturalist of the time noted one such sugar plantation: "The slaves numbered roughly one hundred men and women of different ages, all engaged in digging ditches in a cane field, most of them naked or dressed in rags.

Their arms and legs, worn out by excessive heat, by the weight of their picks and by the resistance of the clayey soil become so hardened that it broke their tools, the slaves nevertheless made tremendous efforts to overcome all obstacles.

[48] "They gather together in the woods and live there exempt from service to their masters without any other leader but one elected among them; others, under cover of the cane fields by day, wait at night to rob those who travel along the main roads, and go from plantation to plantation to steal farm animals to feed themselves, hiding in the living quarters of their friends who, ordinarily, participate in their thefts and who, aware of the goings on in the master's house, advise the fugitives so that they can take the necessary precautions to steal without getting caught.

[51][52] Saint-Domingue gradually increased its reliance on indentured servants (known as petits blanchets or engagés) and by 1789 about 6 percent of all white Creoles were employed as labor on plantations along with slaves.

The elite planters intended to take control of the island and create favorable trade regulations to further their own wealth and power and to restore social & political equality granted to the Creoles.

"The rebellion was extremely violent ... the rich plain of the North was reduced to ruins and ashes ..."[56] Within two months, the slave revolt in northern Saint-Domingue killed 2,000 Creoles and burned 280 sugar plantations owned by grand blancs.

"Many gens de couleur, the affranchis (ex-slaves) and Creole residents of the colony whose rights were restored by the French National Convention as part of the decree of 15 May 1792, asserted that they could form the military backbone of Republican Saint-Domingue; Sonthonax rejected this view as outdated in the wake of the August 1791 slave uprising.

[66] Louverture promulgated the Constitution of 1801 on 7 July, officially establishing his authority as governor general "for life" over the entire island of Hispaniola and confirming most of his existing policies.

Toussaint Louverture, however, understood that they formed a vital part of the economy in Saint-Dommingue as a middle class, and in the hopes of slowing the impending economic collapse, he invited them to return.

He gave property settlements and indemnities for war time losses, and promised equal treatment in his new Saint-Domingue; a good number of white Creole refugees did return.

A passage from the personal secretary of the later King of Northern Haiti (1811–1820), Henry I describes punishments some slaves received: Have they not hung up men with heads downward, drowned them in sacks, crucified them on planks, buried them alive, crushed them in mortars?

He decreed that all those suspected of conspiring in the acts of the expeditionary army should be put to death, including Creoles of color and freed slaves deemed traitors to Dessalines' regime.

Dessalines demanded that all blacks work either as soldiers to defend the nation or return to the plantations as labourers, so as to raise commodity crops such as sugar and coffee for export to sustain his new empire.

Dessalines was assassinated on 17 October 1806 by rebels led by Haitian generals Henri Christophe and Alexandre Pétion; his body was found dismembered and mutilated.

Between 1791 and 1810, more than 25,000 Creoles – planters, poorer whites ("petits blancs"), and free people of color ("gens de couleur libres"), as well as the slaves who accompanied them – fled primarily to the United States in 1793, Jamaica in 1798, and Cuba in 1803.

Newspaper articles from the period reveal that the French king knew the Haitian government was hardly capable of making these payments, as the total was more than 10 times Haiti's annual budget.

With the threat of violence looming, on July 11, 1825, Haitian president Jean-Pierre Boyer signed the document, which stated, "The present inhabitants of the French part of St. Domingue shall pay … in five equal installments … the sum of 150,000,000 francs, destined to indemnify the former colonists."

Researchers have found that the independence debt and the resulting drain on the Haitian treasury were directly responsible not only for the underfunding of education in 20th-century Haiti, but also lack of health care and the country's inability to develop public infrastructure.