Captaincy General of Santo Domingo

[1] Due to its strategic location, the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo served as headquarters for Spanish conquistadors on their way to the mainland and was important in the establishment of other European colonies in the Western Hemisphere.

Spain finally ceded the western third of Hispaniola to France in the 1697 Peace of Ryswick, thus establishing the basis for the future nations of the Dominican Republic and Haiti.

On his first voyage the navigator Christopher Columbus, arrived in 1492 under the Spanish Crown as he landed on a large island in the region of the western Atlantic Ocean that later came to be known as the Caribbean.

[citation needed] In 1496, his brother Bartholomew Columbus established the settlement of Santo Domingo de Guzmán on the southern coast, which became the new capital.

When Christopher Columbus returned to America in 1498 on his third voyage, he began a pact with the rebels, which was signed in August 1499, where he agreed to allow the use of the indigenous people as personal service, and gave back pay for the last two years.

In June 1502,[11] Santo Domingo was destroyed by a major hurricane, and the new Governor Nicolás de Ovando had it rebuilt on a different site on the other side of the Ozama River.

The Spanish monarchs, Ferdinand I and Isabella granted permission to the colonists of the Caribbean to import African slaves, and in 1510 the first sizable shipment consisting of 250 Black Ladinos arrived in Hispaniola from Spain.

[16] The need for a labor force to meet the growing demands of sugar cane cultivation led to an exponential increase in the importation of slaves over the following two decades.

The sugar mill owners soon formed a new colonial elite, and initially convinced the Spanish king to allow them to elect the members of the Real Audiencia from their ranks.

[3]: 143–144, 147 The first major slave revolt in the Americas occurred in Santo Domingo on 26 December 1522, when enslaved Muslims of the Wolof nation led an uprising in the sugar plantation of admiral Don Diego Colón, son of Christopher Columbus.

Many of these insurgents managed to escape to the mountains where they formed independent maroon communities in the south of the island, but the Admiral also had a lot of captured rebels hanged.

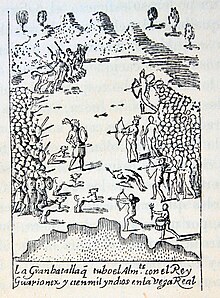

[17] Another rebel also fought back, the native Taino Enriquillo led a group who fled to the mountains and attacked the Spanish repeatedly for fourteen years.

In 1541, Spain authorized the construction of Santo Domingo's fortified wall, and decided to restrict sea travel to enormous, well-armed convoys.

In another move, which would destroy Hispaniola's sugar industry, Havana, more strategically located in relation to the Gulf Stream, was selected as the designated stopping point for the merchant flotas, which had a royal monopoly on commerce with the Americas.

Except for the city of Santo Domingo, which managed to maintain some legal exports, Dominican ports were forced to rely on contraband trade, which, along with livestock, became the sole source of livelihood for the island dwellers.

[18] Drake's invasion signaled the decline of Spanish dominion over the Caribbean region, which was accentuated in the early 17th century by policies that resulted in the depopulation of most of the island outside of the capital.

The pirates were attacked in 1629 by Spanish forces commanded by Don Fadrique de Toledo, who fortified the island, and expelled the French and English.

Intermittent clashes between French and Spanish colonists followed, even after the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick recognized the de facto occupations of France and Spain around the globe.

In 1777, the Treaty of Aranjuez established a definitive border between what Spain called Santo Domingo and what the French named Saint-Domingue, thus ending 150 years of local conflicts and imperial ambitions to extend control over the island.

By the middle of the century, the population was bolstered by emigration from the Canary Islands, resettling the northern part of the colony and planting tobacco in the Cibao Valley, and importation of slaves was renewed.

[29] Dominicans constituted one of the many diverse units which fought under Bernardo de Gálvez during the Spanish recapture of Florida from Britain during the American Revolutionary War.

[30][31] Dominican privateers had already been active in the Guerra del Asiento decades prior, and they sharply reduced the amount of enemy trade operating in West Indian waters.

As a result of these developments, Spanish privateers frequently sailed back into Santo Domingo with their holds filled with captured plunder which were sold in Hispaniola's ports, with profits accruing to individual sea raiders.

[36][37] With the outbreak of the Haitian Revolution, the rich urban families linked to the colonial bureaucracy left the island, while most of the rural cattle ranchers remained, even though they lost their principal market.

This period called the Era de Francia, lasted until 1809 until being recaptured by the Dominican general Juan Sánchez Ramírez in the reconquest of Santo Domingo.

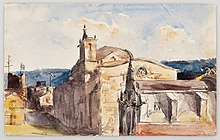

In 1527 the diocese of Concepción de la Vega was abolished, leaving the entire island of Hispaniola under the jurisdiction of the bishop of Santo Domingo.

It was elevated to Metropolitan Archdiocese on February 12, 1546, through the bull Super universas orbis ecclesiae of Pope Paul III, being its first archbishop Alonso de Fuenmayor.

In order to counteract the depopulation and impoverishment of the colony, the Spanish Monarchy allowed the importation of African slaves to hew sugar cane.

[41] Limpieza de sangre (Spanish: [limˈpjeθa ðe ˈsaŋɡɾe], meaning literally "cleanliness of blood") was very important in Mediæval Spain,[42] and this system was replicated on the New World.

In the neighborhood of La Concepción, north of Santo Domingo, the adelantado of Santiago heard rumors of a 15,000-man army of Tainos planning to stage a rebellion.