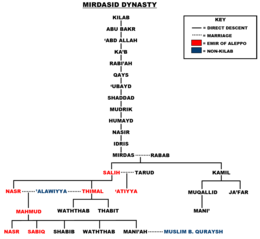

Salih ibn Mirdas

During this tribal rebellion, Salih annexed the central Syrian towns of Homs, Baalbek and Sidon, before conquering Fatimid-held Aleppo in 1025, bringing "to success the plan which guided his [Banu Kilab] forebears for a century", according to historian Thierry Bianquis.

Militarily, he relied on the Banu Kilab, while entrusting fiscal administration to his local Christian vizier, policing to the aḥdāth (urban militia) under Salim ibn Mustafad, and judicial matters to a Shia Muslim qāḍī (head judge).

His alliance with the Banu Tayy ultimately drew him into conflict with the Fatimid general, Anushtakin al-Dizbari, whose forces killed Salih in the Battle of al-Uqhuwana near Lake Tiberias.

[8] Through their military strength and consistent ambition to govern and keep order in the territories they inhabited, the Kilab persisted as a powerful force in northern Syria throughout the following centuries.

[9] In 932–933, another wave of Kilabi tribesmen moved to the environs of Aleppo as soldiers of an invading Qarmatian army; according to the historian Suhayl Zakkar, the new arrivals "paved the way to the rise and establishment of the Mirdasid dynasty".

[10] By then, the Kilab had established itself as the dominant tribal force in northern Syria and played a significant role in all of the uprisings and internecine fighting involving the Hamdanid rulers of Aleppo, between 945 and 1002.

[18] Upon hearing of Muqallid's death and his failed siege, Mansur returned the prisoners to the citadel's dungeons, where many among them, including some chieftains, were executed or died from torture or poor conditions.

[22] Meanwhile, the agreement between Salih and Mansur collapsed as the latter abandoned most of his promises, including giving his daughter's hand in marriage and according the Kilab their share of Aleppo's revenues.

[23] Basil may have also acquiesced to Salih's activities to avoid provoking Bedouin raids against his territory, which bordered the emirates of both the Kilab and their Numayri kinsmen.

[23][note 2] The withdrawal of Byzantine troops weakened Mansur's position further and strengthened Salih, who dispatched one of his sons to Constantinople to pay allegiance to Basil.

[27] Fath responded favorably, but Aleppo's inhabitants protested the rumored deal, demanding the establishment of Fatimid rule; they enjoyed al-Hakim's tax exemptions and opposed Bedouin governance.

[29] He established his own administration and tribal court, which as early as 1019, was visited by the Arab poet Ibn Abi Hasina, who became a prominent panegyrist of the Mirdasid dynasty.

[15] The contemporary historian Yahya al-Antaki relates that the alliance was a renewal of a previous pact made by the same parties in c. 1021, since which they rebelled against and ultimately reconciled with the new Fatimid caliph, az-Zahir (r. 1021–1036), who took power in the aftermath of al-Hakim's disappearance in 1021.

[36] A Bedouin alliance of this magnitude and nature had not occurred since the 7th century and was made without consideration to the traditional Qaysi–Yamani rivalry between the tribes; the Tayy and Kalb were Yamani, while the Kilab were Qaysi.

[34] Moreover, its formation surprised Syria's population at the time, who were unaccustomed to the spectacle of Bedouin chiefs seeking kingship in the cities rather than nomadic life in the desert fringe.

[36] In 1023, Salih and his Kilabi forces headed south and helped the Tayy evict Anushtakin's Fatimid troops from the interior regions of Palestine.

[37] The Tayy and Kalb's revolts in Palestine and Jund Dimashq (Damascus Province), respectively, "supplied the impetus", according to Zakkar, for Salih to move on Aleppo, particularly as the Fatimids' grip on that city had been weakened.

[30] While he fought alongside his allies in the south, his kātib (secretary), Sulayman ibn Tawq, captured Ma'arrat Misrin in Aleppo's southern countryside from its Fatimid governor.

[37] In October 1024, Salih's forces, led by Ibn Tawq, advanced against Aleppo and fought in sporadic engagements with the Fatimid troops of governors Thu'ban and Mawsuf.

[40] The Fatimid garrison's appeal for a truce on 6 June was ignored, prompting their desperate calls for Byzantine assistance; the troops went so far as to hang Christian crosses on the citadel walls and loudly praise Basil II while cursing Caliph az-Zahir.

[39] On his way back to Aleppo, Salih captured a string of towns and fortresses, namely Baalbek west of Damascus, Homs and Rafaniyya in central Syria, Sidon on the Mediterranean coast and Hisn Ibn Akkar in the hinterland of Tripoli.

[39][42] These strategically valuable towns gave Salih's emirate an outlet to the sea and control over part of the trade route between Aleppo and Damascus.

[42] To that end, he maintained the fiscal administration, appointed a vizier to administer civilian and military affairs, and a Shia qāḍī to oversee judicial matters.

[49] Aleppine Christians would largely monopolize the post of vizier under later Mirdasid rulers,[50] and members of the community managed significant parts of the emirate's economy.

His only known institutional innovation was the post of shaykh al-dawla (chieftain of the state) or raʾīs al-balad (municipal chief), who came from a prominent leading family and served as Salih's trusted confidant and permanent representative with the people of Aleppo.

[53] Salih appointed Ibn Mustafad to the post and utilized the latter's aḥdāth, which consisted of armed young men from the city's lower and middle classes, as a police force.

[56] According to historian Thierry Bianquis, Salih had "brought to success the plan which guided his [Kilabi] forebears for a century", and that he ruled with "concern for order and respectability".

[42] Moreover, the Fatimids would not permanently tolerate independent rule in Palestine: as Egypt's gateway to Southwest Asia, this posed a threat to the Caliphate's survival.

[66] In November 1028, Anushtakin returned to Palestine with a large Fatimid army and more horsemen from the Kalb and Banu Fazara to drive out the Tayy and evict the Mirdasids from central Syria.

[67]The Fatimids proceeded to conquer Sidon, Baalbek, Homs, Rafaniyya and Hisn Ibn Akkar from Salih's deputy governors, who all fled.