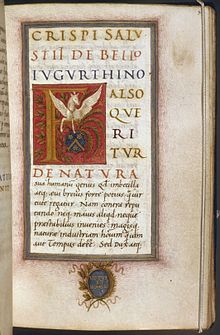

Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (/ˈsæləst/, SAL-əst; c. 86–35 BC),[1] was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family.

[23] Sallust's political affiliation is unclear in this early period,[24] but after he was expelled from the senate in 50 BC by Appius Claudius Pulcher (then serving as censor), he joined Caesar.

[26][25] During the civil war from 49 to 45 BC, Sallust was a Caesarian partisan, but his role was not significant; his name is not mentioned in the dictator's Commentarii de Bello Civili.

[28] In 49 BC, Sallust was moved to Illyricum and probably commanded at least one legion there after the failure of Publius Cornelius Dolabella and Gaius Antonius.

[19] In 46 BC, he served as a praetor[31] and accompanied Caesar in his African campaign, which ended in another defeat of the remaining Pompeians at Thapsus.

[25] Some historians, however, give it an earlier date of composition, perhaps as early at 50 BC as an unpublished pamphlet which was reworked and published after the civil wars.

[43] It may have been written as "a plea for common sense" during the proscriptions of the Second Triumvirate, with its depiction of Caesar opposing the death penalty contrasting with the then-current slaughter.

[44] It is Sallust's first published work, detailing the attempt by Lucius Sergius Catilina to overthrow the Roman Republic in 63 BC.

[citation needed] He presents a narrative condemning the conspirators without doubt, likely relying on Cicero's De consulatu suo (lit.

'On his [Cicero's] consulship') for details of the conspiracy;[45] his narrative focused, however, on Caesar and Cato the Younger, who are held up as "two examples of virtus ('excellence')" with long speeches describing a debate on the punishment of the conspirators in the last section.

[48] Sallust likely relied on a general annalistic history of the time, as well as the autobiographies of Marcus Aemilius Scaurus, Publius Rutilius Rufus, and Sulla.

[citation needed] Two letters (Duae epistolae de republica ordinanda), letters of political counsel and advice addressed to Caesar, and an attack upon Cicero (Invectiva or Declamatio in Ciceronem), frequently attributed to Sallust, are thought by modern scholars to have come from the pen of a rhetorician of the first century AD, along with a counter-invective attributed to Cicero.

At one time Marcus Porcius Latro was considered a candidate for the authorship of the pseudo-Sallustian corpus, but this view is no longer commonly held.

[51] In this, he felt a "pervasive pessimism" with decline that was "both dreadful and inevitable", a consequence of political and moral corruption itself caused by Rome's immense power:[47] he traced the civil war to the influx of wealth from conquest and the absence of serious foreign threats to hone and exercise Roman virtue at arms.

[52] For Sallust, the defining moments of the late republic were the destruction of Rome's old foe, Carthage, in 146 BC and the influx of wealth from the east after Sulla's First Mithridatic War.

[53] At the same time, however, he conveyed a "starry-eyed and romantic picture" of the republic before 146 BC, with this period described in terms of "implausibly untrammelled virtue" that romanticised the distant past.

[56] Ronald Syme suggests that Sallust's choice of style and even particular words was influenced by his antipathy to Cicero, his rival, but also one of the trendsetters in Latin literature in the first century BC.

[57] More recent scholars agree, describing Sallust's style as "anti-Ciceronian", eschewing the harmonious structure of Cicero's sentences for short and abrupt descriptions.

[59] Sallust avoids common words from public speeches of contemporary Roman political orators, such as honestas, humanitas, consensus.

[60] In several cases he uses rare forms of well-known words: for example, lubido instead of libido, maxumum instead of maximum, the conjunction quo in place of more common ut.

[64] In late antiquity, he was highly praised by Jerome as "very reliable"; his monographs also entered the corpus of standard education in Latin, with Virgil, Cicero, and Terence (covering history, the epic, oratory, and comedy, respectively).

Also importantly, much of Sallust's anti-corruption moralising is "blunted by his sanctimonious tone and by ancient accusations of corruption, which have made him out to be a remarkable hypocrite".

[70] Modern views on the period which Sallust documented reject moral failure as a cause of the republic's collapse and believe that "social conflicts are insufficient to account for the political implosion".

[71] The core narrative of moral decline prevalent in Sallust's works, is now criticised as crowding out his own examination of the structural and socio-economic factors that brought about the crisis of the republic while also manipulating historical facts to make them fit his moralistic thesis; he, however, is credited as "a clear-sighted and impartial interpreter of his own age".

He has great interest in moralising, and for this reason, he tends to paint an exaggerated picture of the senate's faults... he analyses events in terms of a simplistic opposition between the self-interest of Roman politicians and the "public good" that shows little understanding of how the Roman political system actually functioned...[73] The reality was more complicated than Sallust's simplistic moralising would suggest.

For example, Gaius Asinius Pollio criticized Sallust's addiction to archaic words and his unusual grammatical features.

[80] Though Quintilian has a generally favorable opinion of Sallust, he disparages several features of his style: For though a diffuse irrelevance is tedious, the omission of what is necessary is positively dangerous.

We must therefore avoid even the famous terseness of Sallust (though in his case of course it is a merit), and shun all abruptness of speech, since a style which presents no difficulty to a leisurely reader, flies past a hearer and will not stay to be looked at again.