Salsa music

[32][33][34] The instrumentation in salsa bands is mostly based on the son montuno ensemble developed by Arsenio Rodríguez, who added a horn section, as well as tumbadoras (congas) to the traditional Son cubano ensemble; which typically contained bongos, bass, tres, one trumpet, smaller hand-held percussion instruments (like claves, güiro, or maracas) usually played by the singers, and sometimes a piano.

Nonetheless, some bands instead follow the Charanga format, which consists of a string section (of violins, viola, and cello), tumbadoras (congas), timbales, bass, flute, claves and güiro.

[39] During the 1950s, New York became a hotspot of Mambo with musicians like the aforementioned Pérez Prado, Luciano "Chano" Pozo, Mongo Santamaría, Machito and Tito Puente.

Musicians who would become great innovators of mambo, like Mario Bauzá and Chano Pozo, began their careers in New York working in close conjunction with some of the biggest names in jazz, like Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, and Dizzy Gillespie, among others.

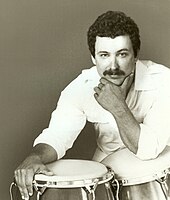

By the early 1960s, there were several charanga bands in New York led by musicians (like Johnny Pacheco, Charlie Palmieri, Mongo Santamaría and Ray Barretto) who would later become salsa stars.

During that period his success was limited (NYC was more interested in Mambo), but his guajeos (who influenced the musicians he shared the stage with, such as Chano Pozo, Machito, and Mario Bauzá), together with the piano tumbaos of Lilí Martínez, the trumpet of Félix Chappottín and the rhythmic lead vocals of Roberto Faz would become very relevant in the region a decade later.

They introduced many of the artists that would later be identified with the salsa movement, including Willie Colón, Celia Cruz, Larry Harlow, Ray Barretto, Héctor Lavoe and Ismael Miranda.

Pacheco put together a team that included percussionist Louie Ramírez, bassist Bobby Valentín and arranger Larry Harlow to form the Fania All-Stars in 1968.

Meanwhile, the Puerto Rican band La Sonora Ponceña recorded two albums named after songs of Arsenio Rodriguez (Hachero pa' un palo and Fuego en el 23).

"[45] During the same period, Cuban super group Irakere fused bebop and funk with batá drums and other Afro-Cuban folkloric elements; Orquesta Ritmo Oriental created a new highly syncopated, rumba-influenced son in the charanga ensemble; and Elio Revé developed changüí.

Motivated primarily by economic factors, Fania's push for countries throughout Latin America to embrace salsa did result in an expanded market.

[48] By the early 1970s, the music's center moved to Manhattan and the Cheetah, where promoter Ralph Mercado introduced many future Puerto Rican salsa stars to an ever-growing and diverse crowd of Latino audiences.

Dawson helped to broaden New York's salsa audience and introduced new artists such as the bilingual Ángel Canales who were not given play on the Hispanic AM stations of that time.

[55] An exception of this is probably found in the work of Eddie Palmieri and Manny Oquendo, who were considered more adventurous than the highly produced Fania records artists.

[citation needed] During the 1980s, several Latin American countries, such as Colombia, Venezuela, Peru, Mexico and Panama, began producing their own salsa music.

[60] Timba was created by musicians of Irakere who later formed NG La Banda under the direction of Jose Luis "El Tosco" Cortez.

While the Puerto Rican bands Batacumbele (featuring a young Giovanni Hidalgo) and Zaperoko fully embraced songo music under the mentorship of Changuito.

Salsa romántica can be traced back to Noches Calientes, a 1984 album by singer José Alberto "El Canario" with producer Louie Ramírez.

Sergio George produced several albums that mixed salsa with contemporary pop styles with Puerto Rican artists like Tito Nieves, La India, and Marc Anthony.

Brenda K. Starr, Son By Four, Víctor Manuelle, and the Cuban-American singer Gloria Estefan enjoyed crossover success within the Anglo-American pop market with their Latin-influenced hits, usually sung in English.

Shortly thereafter during a radio interview in San Juan (Puerto Rico), he exclaimed that his commercial success proved that you did not need to know about clave to make it in Latin music.

As influential as Manolín was from a strictly musical point of view, his charisma, popularity and unprecedented earning power had an even more seismic impact, causing a level of excitement among musicians that had not been seen since the 1950s.

Some of the other important timba bands include Azúcar Negra, Manolín "El Médico de la salsa", Havana d'Primera, Klimax, Paulito FG, Salsa Mayor, Tiempo Libre, Pachito Alonso y sus Kini Kini, Bamboleo, Los Dan Den, Alain Pérez, Issac Delgado, Tirso Duarte, Klimax, Manolito y su Trabuco, Paulo FG, and Pupy y Los que Son Son.

[68][69] A few years later the Cuban reggaeton band Gente de Zona and Marc Anthony produced the timba-reggaeton international mega-hit La Gozadera reaching over a billion views in YouTube.

John Storm Roberts states: "It was the Cuban connection, but increasingly also New York salsa, that provided the major and enduring influences—the ones that went deeper than earlier imitation or passing fashion.

[75] The Senegalese band Orchestra Baobab plays in a basic salsa style with congas and timbales, but with the addition of Wolof and Mandinka instruments and lyrics.

Salsa lyrics range from simple dance numbers, and sentimental romantic songs, to risque and politically radical subject matter.

[80] Politically and socially activist composers have long been an important part of salsa, and some of their works, like Eddie Palmieri's "La libertad - lógico", became Latin, and especially Puerto Rican anthems.

The Panamanian singer Ruben Blades in particular is well known for his socially-conscious and incisive salsa lyrics about everything from imperialism to disarmament and environmentalism, which have resonated with audiences throughout Latin America.

[81] Many salsa songs contain a nationalist theme, centered around a sense of pride in black Latino identity, and may be in Spanish, English or a mixture of the two called Spanglish.