Salvadoran Civil War

"[citation needed] A threat to land change meant a challenge to a state where "marriages intertwined, making the wealthiest coffee processors and exporters (more so than the growers) also those with the highest ties in the military.With tensions mounting and the country on the verge of an insurrection, the civil-military Revolutionary Government Junta (JRG) deposed Romero in a coup on 15 October 1979.

[59] The JRG enacted a land reform program that restricted landholdings to a 100-hectare maximum, nationalised the banking, coffee and sugar industries, scheduled elections for February 1982, and disbanded the paramilitary private death squad Organización Democrática Nacionalista (ORDEN) on 6 November 1979.

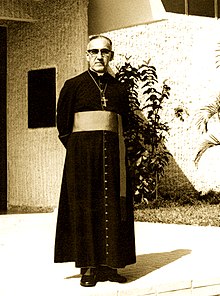

[75] In February 1980, Archbishop Óscar Romero published an open letter to US President Jimmy Carter in which he pleaded with him to suspend the United States' ongoing program of military aid to the Salvadoran regime.

[79] A week after the arrest of D'Aubuisson, the National Guard and the newly reorganized paramilitary ORDEN, with the cooperation of the Military of Honduras, carried out a large massacre at the Sumpul River on 14 May 1980, in which an estimated 600 civilians were killed, mostly women and children.

[83] White was dismissed from the foreign service by the Reagan administration after he had refused to participate in a coverup of the Salvadoran military's responsibility for the murders at the behest of Secretary of State Alexander Haig.

In its report covering 1981, Amnesty International identified "regular security and military units as responsible for widespread torture, mutilation and killings of noncombatant civilians from all sectors of Salvadoran society."

[109] A US congressional delegation that, on 17–18 January 1981, visited the refugee camps in El Salvador on a fact finding mission, submitted a report to Congress that found: "[T]he Salvadoran method of 'drying up the ocean' is to eliminate entire villages from the map, to isolate the guerrillas, and deny them any rural base off which they can feed.

An Americas Watch report described that the Socorro Jurídico figures "tended to be conservative because its standards of confirmation are strict"; killings of persons were registered individually and required proof of being "not combat related".

Roberto D'Aubuisson accused Jaime Abdul Gutiérrez Avendaño of imposing on the Assembly "his personal decision to put Álvaro Alfredo Magaña Borja in the presidency" in spite of a "categorical no" from the ARENA deputies.

The Apaneca Pact was signed on 3 August 1982, establishing a Government of National Unity, whose objectives were peace, democratization, human rights, economic recovery, security and a strengthened international position.

[122] The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights reported that, on 24 May 1982, a clandestine cemetery containing the corpses of 150 disappeared persons was discovered near Puerta del Diablo, Panchimalco, approximately twelve kilometers from San Salvador.

"[126] In March 1983, Marianella García Villas, president of the non-governmental Human Rights Commission of El Salvador, was captured by army troops on the Guazapa volcano, and later tortured to death.

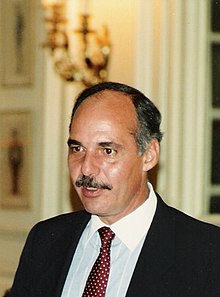

In 1984 elections, Christian Democrat José Napoleón Duarte won the presidency (with 54 percent of the votes) against Army Major Roberto d'Aubuisson of the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA).

[139] In its annual review of 1987, Amnesty International reported that "some of the most serious violations of human rights are found in Central America", particularly Guatemala and El Salvador, where "kidnappings and assassinations serve as systematic mechanisms of the government against opposition from the left".

Nearly two weeks earlier, US Vice President Dan Quayle on a visit to San Salvador told army leaders that human rights abuses committed by the military had to stop.

[152] In a 29 November 1989 press conference, Secretary of State James A. Baker III said he believed President Cristiani was in control of the army and defended the government's crackdown on opponents as "absolutely appropriate".

[154][155] In San Salvador on 1 October 1989, eight people were killed and 35 others were injured when a death squad bombed the headquarters of the leftist labor confederation, the National Trade Union Federation of Salvadoran Workers (UNTS).

[156] Earlier the same day, another bomb exploded outside the headquarters of a victims' advocacy group, the Committee of Mothers and Family Members of Political Prisoners, Disappeared and Assassinated of El Salvador, injuring four others.

Opposition politicians, members of church and grassroots organizations representing peasants, women and repatriated refugees suffered constant death threats, arrests, surveillance and break-ins all year.

[177][178] The statistics presented in the Truth Commission's report are consistent with both previous and retrospective assessments by the international community and human rights monitors, which documented that the majority of the violence and repression in El Salvador was attributable to government agencies, primarily the National Guard and the Salvadoran Army.

[179][180][181] A 1984 Amnesty International report stated that many of the 40,000 people killed in the preceding five years had been murdered by government forces, who openly dumped their mutilated corpses in an apparent effort to terrorize the population.

[186][187] Cynthia Arnson, a Latin American-affairs writer for Human Rights Watch, says: the objective of death-squad-terror seemed not only to eliminate opponents, but also, through torture and the gruesome disfigurement of bodies, to terrorize the population.

The same day, Reni Roldán resigned from the Commission of National Reconciliation, saying: "The murder of Anaya, the disappearance of university labor leader Salvador Ubau, and other events do not seem to be isolated incidents.

United Nations Secretary General Javier Pérez de Cuéllar, Americas Watch, Amnesty International, and other organizations protested against the assassination of the leader of the Human Rights Commission of El Salvador.

In 2008 the Spanish Association for Human Rights and a California organization called the Center for Justice and Accountability jointly filed a lawsuit in Spain against former President Cristiani and former defense minister Larios in the matter of the 1989 slaying of several Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her daughter.

[192] Long after the war, in a U.S. federal court, in the case of Ford vs. García the families of the murdered Maryknoll nuns sued the two Salvadoran generals believed responsible for the killings, but lost; the jury found Gen. Carlos Eugenio Vides Casanova, ex-National Guard Leader and Duarte's defense minister, and Gen. José Guillermo García—defense minister from 1979 to 1984, not responsible for the killings; the families appealed and lost, and, in 2003, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to hear their final appeal.

A second case, against the same generals, succeeded in the same Federal Court; the three plaintiffs in Romagoza vs. García won a judgment exceeding US$54 million compensation for having been tortured by the military during El Salvador's Civil War.

The Spanish Judge Velasco who issued indictments and arrest warrants for 20 former members of the Salvadoran military, charged with murder, Crimes Against Humanity and Terrorism requested that U.S. agencies declassify documents related to the killings of the Jesuits, their housekeeper and her daughter but were denied access.

Many of the documents, from the CIA and the Defense Department, are not available..."[194] The Cold War with the Soviet Union and other communist nations at least partially explains the backdrop against which the U.S. government aided various pro-government Salvadoran groups and opposed the FMLN.

[198] After a 2012 historians seminar at the University of El Salvador commemorating the 20th anniversary of the peace accords, Michael Allison concluded: "Most postwar discourse has been driven by elites who participated in the conflict either on the part of the guerrillas or the government.