Salvadoran literature

Religious authorities zealously controlled the lives of recent converts to Christianity, insisting that literary expression be in the service of faith and under their careful scrutiny.

This literature tended to imitate the metropolitan canons, though occasionally nourished an original and memorable voice like that of Mexican poet Juana Inés de la Cruz.

In the latter group are pious works, hagiographies portraying the lives of saints, and theological treatises, written by clergy born in the county, but generally published in Europe.

He wrote treatises including Misteriosa sombra de las primeras luces del divino Osiris and Jesús recién nacido.

Father Bartolomé Cañas, also a Jesuit, sought asylum in Italy after being expelled from his order in the Spanish territories; in Bologna he wrote a major apologetic dissertation.

This encouraged the emergence of a literature more political than aesthetic, manifested principally in oratory and argumentative prose, both polemic and doctrinal, in which authors demonstrated their ingenuity and use of classical rhetoric.

One major figure of this era was Father Manuel Aguilar (1750–1819), whose famous homily proclaimed the right of insurrection of oppressed peoples, provoking scandal and censorship.

Literature was used only occasionally, such as anonymous verses offering satirical comment on contemporary politics, or other poetry celebrating the good name and deeds of important figures.

This peculiar attitude toward the aesthetic contributed to the increased social standing of poets and made literature an important element in the legitimization of the state.

La Juventud denounced the teaching of Fernando Velarde, a Spaniard who lived in the country during the 1870s, influencing young writers with his dreamy and grandiloquent poetry.

Among these authors were Juan José Cañas (1826–1918) (lyricist of the national anthem),[3] Rafael Cabrera, Dolores Arias, Antonio Guevara Valdés, and Isaac Ruiz Araujo.

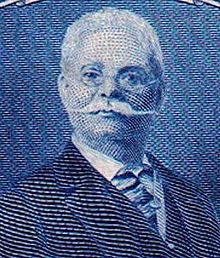

The model of liberal cultural modernization appeared to be consolidated under the short-lived government of Manuel Enrique Araujo, who enjoyed support among intellectuals and seemed committed to a policy encouraging science and the arts.

Araujo tried to give a stronger institutional base to the model of scientific literary societies with the founding of the Ateneo de El Salvador (association for the study of national history and writing), but this impulse was cut short by his assassination in 1913.

The Salvadoran literary scene, which had previously embodied a cosmopolitan aesthetic spirit, was poorly equipped to deal with the country's new political reality.

As a result, different manners of portraying local customs and everyday life arose, whether satirical or analytic, and writers began to turn their attention to matters previously neglected in literary expression.

One major writer in the costumbrismo tradition was General José María Peralta Lagos (1873-1944), Minister of War under Manuel Enrique Araujo and, under the nom de plume T.P.

Ambrosi's originality lay in his thematic shift toward traditions native to El Salvador and his synthesis of literary language and vernacular dialect.

President Pío Romero Bosque had begun a process to return to institutional legality, calling the first free elections in Salvadorean history.

Modernists in the mold of Rubén Darío frequently condemned the prosaic nature of the times, yet were dazzled by the opulence and refinement of turn-of-the-century Europe.

This search for alternatives led many to embrace Eastern mysticism, Amerindian cultures, and primitivism that saw the antithesis of disenchanted modernity in traditional ways of life.

These ideas were particularly attractive to a group of writers including Alberto Guerra Trigeros, Salarrué (1899-1975), Claudia Lars (1899-1974), Serafín Quiteño, Raúl Contreras, Miguel Ángel Espino, Quino Caso, Juan Felipe Toruño.

Though lyricism of a classical mold was more popular among his contemporaries (who also were distancing themselves from modernism), Guerra Trigueros's became more visible in the following generations (for example, in the writing of Pedro Geoffroy Rivas, Oswaldo Escobar Velado, and Roque Dalton).

Though the members of this generation of writers did not always have direct links with the military dictatorship installed in 1931, their conception of national culture as a negation of an enlightened ideal helped legitimate the new order.

The idealization of the traditional peasant and his solitary link with nature permitted the association of authoritarianism with populism, which was essential to the emerging discourse of the military dictatorship.

1922), Joaquín Hernández Callejas (1915–2000), Julio Fausto Fernández, Oswaldo Escobar Velado, Luis Gallegos Valdés, Antonio Gamero, Ricardo Trigueros de León, and Pedro Quiteno (1898–1962).

Pedro Geoffroy Rivas produced lyrical literature marked by avant-gardism and played an important role in the rescue of indigenous traditions and popular language.

Overtime, people began to write on deeper and more sensitive subjects as the government developed and adjusted to advanced freedom compared to ancient history.

This group of writers practiced mainly poetry, which was marked by their participation in the popular organization of the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN) during the civil war in El Salvador.

Although the war had taken its toll on the dead and exiles, the legacy of Xibalbá and previous generations have created a great responsibility for other young people and groups of writers who will emerge in the next two decades.

Notable members include Amilcar Colocho, Manuel Barrera, Otoniel Guevara, Luis Alvarenga, Silvia Elena Regalado, Antonio Casquín, Dagoberto Segovia, Jorge Vargas Méndez, Álvaro Darío Lara, Eva Ortíz, Arquímides Cruz, Ernesto Deras.