Samkhya

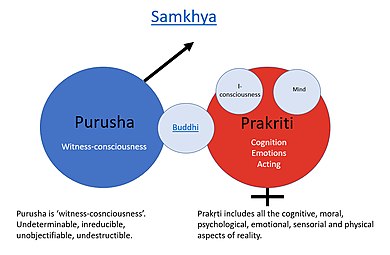

[1][2][3] It views reality as composed of two independent principles, Puruṣa ('consciousness' or spirit) and Prakṛti (nature or matter, including the human mind and emotions).

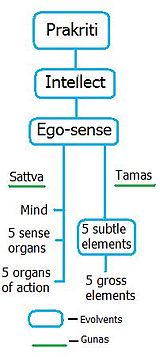

When Prakṛti comes into contact with Purusha this balance is disturbed, and Prakriti becomes manifest, evolving twenty-three tattvas,[10] namely intellect (buddhi, mahat), I-principle (ahamkara), mind (manas); the five sensory capacities known as ears, skin, eyes, tongue and nose; the five action capacities known as hands (hasta), feet (pada), speech (vak), anus (guda), and genitals (upastha); and the five "subtle elements" or "modes of sensory content" (tanmatras), from which the five "gross elements" or "forms of perceptual objects" (earth, water, fire, air and space) emerge,[8][11] in turn giving rise to the manifestation of sensory experience and cognition.

[19][20] While Samkhya-like speculations can be found in the Rig Veda and some of the older Upanishads, some western scholars have proposed that Samkhya may have non-Vedic origins,[21][note 1] developing in ascetic milieus.

Proto-Samkhya ideas developed c. 8th/7th BC and onwards, as evidenced in the middle Upanishads, the Buddhacharita, the Bhagavad Gita, and the Mokshadharma-section of the Mahabharata.

[22] It was related to the early ascetic traditions and meditation, spiritual practices, and religious cosmology,[23] and methods of reasoning that result in liberating knowledge (vidya, jnana, viveka) that end the cycle of duḥkha (suffering) and rebirth[24] allowing for "a great variety of philosophical formulations".

[32] In the context of ancient Indian philosophies, Samkhya refers to the philosophical school in Hinduism based on systematic enumeration and rational examination.

[34] Although the term had been used in the general sense of metaphysical knowledge before,[35] in technical usage it refers to the Samkhya school of thought that evolved into a cohesive philosophical system in early centuries CE.

[34] Samkhya makes a distinction between two "irreducible, innate and independent realities",[37] Purusha, the witness-consciousness, and Prakṛti, "matter", the activities of mind and perception.

It is often mistranslated as 'matter' or 'nature' – in non-Sāṃkhyan usage it does mean 'essential nature' – but that distracts from the heavy Sāṃkhyan stress on prakṛti's cognitive, mental, psychological and sensorial activities.

When this equilibrium of the guṇas is disturbed then unmanifest Prakṛti, along with the omnipresent witness-consciousness, Purusha, gives rise to the manifest world of experience.

[12][13] Prakriti becomes manifest as twenty-three tattvas:[10] intellect (buddhi, mahat), ego (ahamkara) mind (manas); the five sensory capacities; the five action capacities; and the five "subtle elements" or "modes of sensory content" (tanmatras: form (rūpa), sound (shabda), smell (gandha), taste (rasa), touch (sparsha)), from which the five "gross elements" or "forms of perceptual objects" emerge (earth (prithivi), water (jala), fire (Agni), air (Vāyu), ether (Ākāsha)).

[47] Ahamkara, the ego or the phenomenal self, appropriates all mental experiences to itself and thus, personalizes the objective activities of mind and intellect by assuming possession of them.

[52]: 58 Puruṣa, the eternal pure consciousness, due to ignorance, identifies itself with products of Prakṛti such as intellect (buddhi) and ego (ahamkara).

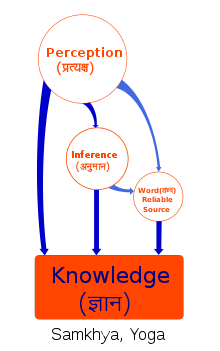

[15] Samkhya considered Pratyakṣa or Dṛṣṭam (direct sense perception), Anumāna (inference), and Śabda or Āptavacana (verbal testimony of the sages or shāstras) to be the only valid means of knowledge or pramana.

[16] Unlike some other schools, Samkhya did not consider the following three pramanas to be epistemically proper: Upamāṇa (comparison and analogy), Arthāpatti (postulation, deriving from circumstances) or Anupalabdi (non-perception, negative/cognitive proof).

As early as 1898, Richard Karl von Garbe, a German professor of philosophy and Indologist, wrote in 1898, The origin of the Sankhya system appears in the proper light only when we understand that in those regions of India which were little influenced by Brahmanism [political connotation given by the Christian missionary] the first attempt had been made to solve the riddles of the world and of our existence merely by means of reason.

"[93] Warder writes, '[Samkhya] has indeed been suggested to be non-Brahmanical and even anti-Vedic in origin, but there is no tangible evidence for that except that it is very different than most Vedic speculation – but that is (itself) quite inconclusive.

[103] The Riddle hymns of the Rigveda, famous for their numerous enumerations, structural language symmetry within the verses and the chapter, enigmatic word play with anagrams that symbolically portray parallelism in rituals and the cosmos, nature and the inner life of man.

[104][109][110] The two birds in this hymn have been interpreted to mean various forms of dualism: "the sun and the moon", the "two seekers of different kinds of knowledge", and "the body and the atman".

Where those fine Birds hymn ceaselessly their portion of life eternal, and the sacred synods, There is the Universe's mighty Keeper, who, wise, hath entered into me the simple.

The tree on which the fine Birds eat the sweetness, where they all rest and procreate their offspring, Upon its top they say the fig is sweetest, he who does not know the Father will not reach it.

[122] A prominent similarity between Buddhism and Samkhya is the greater emphasis on suffering (dukkha) as the foundation for their respective soteriological theories, than other Indian philosophies.

[125] Samkhya and Yoga are mentioned together for first time in chapter 6.13 of the Shvetashvatra Upanishad,[126] as samkhya-yoga-adhigamya (literally, "to be understood by proper reasoning and spiritual discipline").

For example, the fourth to sixth verses of the text states it epistemic premises,[143] Perception, inference and right affirmation are admitted to be threefold proof; for they (are by all acknowledged, and) comprise every mode of demonstration.

[149] In his introduction, the commentator Vijnana Bhiksu stated that only a sixteenth part of the original Samkhya Sastra remained, and that the rest had been lost to time.

[155] The oldest commentary on the Samkhakarika, the Yuktidīpikā, asserts the existence of God, stating: "We do not completely reject the particular power of the Lord, since he assumes a majestic body and so forth.

[154] A majority of modern academic scholars are of view that the concept of Ishvara was incorporated into the nirishvara (atheistic) Samkhya viewpoint only after it became associated with the Yoga, the Pasupata and the Bhagavata schools of philosophy.

While Jakob Wilhelm Hauer and Georg Feuerstein believe that Yoga was a tradition common to many Indian schools and its association with Samkhya was artificially foisted upon it by commentators such as Vyasa.

[169] Dasgupta speculates that the Tantric image of a wild Kali standing on a slumbering Shiva was inspired from the Samkhyan conception of prakṛti as a dynamic agent and Purusha as a passive witness.

While Tantra sought to unite the male and female ontological realities, Samkhya held a withdrawal of consciousness from matter as the ultimate goal.