Yoga

[7][8] Yoga-like practices are mentioned in the Rigveda[9] and a number of early Upanishads,[10][11][12][d] but systematic yoga concepts emerge during the fifth and sixth centuries BCE in ancient India's ascetic and Śramaṇa movements, including Jainism and Buddhism.

[64] James Mallinson disagrees with the inclusion of supernatural accomplishments, and suggests that such fringe practices are far removed from the mainstream Yoga's goal as meditation-driven means to liberation in Indian religions.

"[68] In the second meaning yoga is "that specific system of thought (sāstra) that has for its focus the analysis, understanding and cultivation of those altered states of awareness that lead one to the experience of spiritual liberation.

Between 200 BCE and 500 CE, traditions of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain philosophy were taking shape; teachings were collected as sutras, and a philosophical system of Patanjaliyogasastra began to emerge.

[78] According to Zimmer, yoga is part of a non-Vedic system which includes the Samkhya school of Hindu philosophy, Jainism and Buddhism:[78] "[Jainism] does not derive from Brahman-Aryan sources, but reflects the cosmology and anthropology of a much older pre-Aryan upper class of northeastern India [Bihar] – being rooted in the same subsoil of archaic metaphysical speculation as Yoga, Sankhya, and Buddhism, the other non-Vedic Indian systems.

"[79][note 1] More recently, Richard Gombrich[82] and Geoffrey Samuel[83] also argue that the śramaṇa movement originated in the non-Vedic eastern Ganges basin,[83] specifically Greater Magadha.

[90][89] According to Edward Fitzpatrick Crangle, Hindu researchers have favoured a linear theory which attempts "to interpret the origin and early development of Indian contemplative practices as a sequential growth from an Aryan genesis";[91][note 3] traditional Hinduism regards the Vedas as the source of all spiritual knowledge.

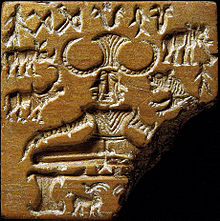

[95] The twentieth-century scholars Karel Werner, Thomas McEvilley, and Mircea Eliade believed that the central figure of the Pashupati seal is seated in the Mulabandhasana posture,[97] and the roots of yoga are in the Indus Valley civilisation.

[96] This is rejected by more recent scholarship; for example, Geoffrey Samuel, Andrea R. Jain, and Wendy Doniger describe the identification as speculative; the meaning of the figure will remain unknown until Harappan script is deciphered, and the roots of yoga cannot be linked to the IVC.

[96][98][note 5] The Vedas, the only texts preserved from the early Vedic period and codified between c. 1200 and 900 BCE, contain references to yogic practices primarily related to ascetics outside, or on the fringes of Brahmanism.

[9] Werner wrote that there were ... individuals who were active outside the trend of Vedic mythological creativity and the Brahminic religious orthodoxy and therefore little evidence of their existence, practices and achievements has survived.

[116][note 8] According to Geoffrey Samuel, the "best evidence to date" suggests that yogic practices "developed in the same ascetic circles as the early śramaṇa movements (Buddhists, Jainas and Ajivikas), probably in around the sixth and fifth centuries BCE."

According to White, The earliest extant systematic account of yoga and a bridge from the earlier Vedic uses of the term is found in the Hindu Katha Upanisad (Ku), a scripture dating from about the third century BCE ... [I]t describes the hierarchy of mind-body constituents—the senses, mind, intellect, etc.—that comprise the foundational categories of Sāmkhya philosophy, whose metaphysical system grounds the yoga of the Yogasutras, Bhagavad Gita, and other texts and schools (Ku3.10–11; 6.7–8).

[139]The hymns in book two of the Shvetashvatara Upanishad (another late-first-millennium BCE text) describe a procedure in which the body is upright, the breath is restrained and the mind is meditatively focused, preferably in a cave or a place that is simple and quiet.

[143][144] According to Charles Rockwell Lanman, these principles are significant in the history of yoga's spiritual side and may reflect the roots of "undisturbed calmness" and "mindfulness through balance" in the later works of Patanjali and Buddhaghosa.

The sutra asserts that yoga leads to an absence of sukha (happiness) and dukkha (suffering), describing meditative steps in the journey towards spiritual liberation.

[166] As the name suggests, the metaphysical basis of the text is samkhya; the school is mentioned in Kauṭilya's Arthashastra as one of the three categories of anviksikis (philosophies), with yoga and Cārvāka.

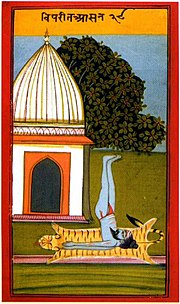

[197] It discusses eight yoga asanas (Swastika, Gomukha, Padma, Vira, Simha, Bhadra, Mukta and Mayura),[198] a number of breathing exercises for body cleansing,[199] and meditation.

At the height of the Gupta period (fourth to fifth centuries CE), a northern Mahayana movement known as Yogācāra began to be systematized with the writings of Buddhist scholars Asanga and Vasubandhu.

George Samuel wrote that tantra is a contested term, but may be considered a school whose practices appeared in nearly-complete form in Buddhist and Hindu texts by about the 10th century CE.

[245] The postural yoga of the Western world is a physical activity consisting of asanas, often connected by smooth transitions, sometimes accompanied by breathing exercises and usually ending with a period of relaxation or meditation.

[268] The effect of yoga as exercise on physical and mental health has been a subject of study, with evidence that regular practice is beneficial for low back pain and stress.

Jain spirituality is based on a strict code of nonviolence, or ahimsa (which includes vegetarianism), almsgiving (dāna), faith in the three jewels, austerities (tapas) such as fasting, and yoga.

[note 21] In early Buddhism, yoga practices included: These meditations were seen as supported by the other elements of the Noble Eightfold Path, such as ethics, right exertion, sense restraint and right view.

It focuses on the study of the Upanishads and the Brahma Sutras (one of its early texts), about gaining spiritual knowledge of Brahman: the unchanging, absolute reality.

[317] Previously, the Roman Catholic Church, and some other Christian organizations have expressed concerns and disapproval with respect to some eastern and New Age practices that include yoga and meditation.

[321] The Vatican warned that concentration on the physical aspects of meditation "can degenerate into a cult of the body" and that equating bodily states with mysticism "could also lead to psychic disturbance and, at times, to moral deviations."

[324][325] Although Al-Biruni's translation preserved many core themes of Patañjali's yoga philosophy, some sutras and commentaries were restated for consistency with monotheistic Islamic theology.

[337] Similar fatwas banning yoga for its link to Hinduism were imposed by Grand Mufti Ali Gomaa in Egypt in 2004, and by Islamic clerics in Singapore earlier.

[340] In May 2009, Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs head Ali Bardakoğlu discounted personal-development techniques such as reiki and yoga as commercial ventures which could lead to extremism.