SS Edmund Fitzgerald

[8] Carrying a full cargo of taconite ore pellets with Captain Ernest M. McSorley in command, she embarked on her ill-fated voyage from Superior, Wisconsin, near Duluth, on the afternoon of November 9, 1975.

The sinking led to changes in Great Lakes shipping regulations and practices that included mandatory survival suits, depth finders, positioning systems, increased freeboard, and more frequent inspection of vessels.

[9] In 1957, they contracted Great Lakes Engineering Works (GLEW), of River Rouge, Michigan, to design and construct the ship "within a foot of the maximum length allowed for passage through the soon-to-be completed Saint Lawrence Seaway.

Although Captain Peter Pulcer was in command of Edmund Fitzgerald on trips when cargo records were set, "he is best remembered ... for piping music day or night over the ship's intercom system" while passing through the St. Clair and Detroit Rivers.

The crew of Wilfred Sykes followed the radio conversations between Edmund Fitzgerald and Arthur M. Anderson during the first part of their trip and overheard their captains deciding to take the regular Lake Carriers' Association downbound route.

[65] Canadian Coast Guard aircraft joined the three-day search and the Ontario Provincial Police established and maintained a beach patrol all along the eastern shore of Lake Superior.

[67] On her final voyage, Edmund Fitzgerald's crew of 29 consisted of the captain; the first, second, and third mates; five engineers; three oilers; a cook; a wiper; two maintenance men; three watchmen; three deckhands; three wheelsmen; two porters; a cadet; and a steward.

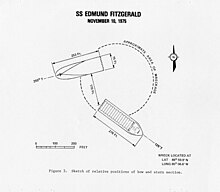

[71] A U.S. Navy Lockheed P-3 Orion aircraft, piloted by Lt. George Conner and equipped to detect magnetic anomalies usually associated with submarines, found the wreck on November 14, 1975 in Canadian waters close to the international boundary at a depth of 530 feet (160 m).

The towed survey system and the Mini Rover ROV were designed, built and operated by Chris Nicholson of Deep Sea Systems International, Inc.[76] Participants included the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the National Geographic Society, the United States Army Corps of Engineers, the Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society (GLSHS), and the United States Fish and Wildlife Service, the latter providing RV Grayling as the support vessel for the ROV.

[85] Shannon determined that based on GPS coordinates from the 1994 Deepquest expedition, "at least one-third of the two acres of immediate wreckage containing the two major portions of the vessel is in U.S. waters because of an error in the position of the U.S.–Canada boundary line shown on official lake charts.

[91] Canadian engineer Phil Nuytten's atmospheric diving suit, known as the Newtsuit, was used to retrieve the bell from the ship, replace it with a replica, and put a beer can in Edmund Fitzgerald's pilothouse.

[109] Captain Cooper of Arthur M. Anderson reported that his ship was "hit by two 30 to 35 foot seas about 6:30 p.m., one burying the aft cabins and damaging a lifeboat by pushing it right down onto the saddle.

[110] This hypothesis postulates that the "three sisters" compounded the twin problems of Edmund Fitzgerald's known list and her lower speed in heavy seas that already allowed water to remain on her deck for longer than usual.

"[123] Maritime authors Bishop and Stonehouse wrote that the shoaling hypothesis was later challenged on the basis of the higher quality of detail in Shannon's 1994 photography that "explicitly show[s] the devastation of the Edmund Fitzgerald".

"[135] George H. "Red" Burgner, Edmund Fitzgerald's steward for ten seasons and winter ship-keeper for seven years, testified in a deposition that a "loose keel" contributed to the vessel's loss.

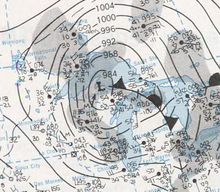

Captain Paquette of Wilfred Sykes had been following and charting the low-pressure system over Oklahoma since November 8 and concluded that a major storm would track across eastern Lake Superior.

[148] After running computer models in 2005 using actual meteorological data from November 10, 1975, Hultquist of the NWS said of Edmund Fitzgerald's position in the storm, "It ended in precisely the wrong place at the absolute worst time.

[148] Mark Thompson, a merchant seaman and author of numerous books on Great Lakes shipping, stated that if her cargo holds had had watertight subdivisions, "the Edmund Fitzgerald could have made it into Whitefish Bay.

The collision tore a hole in the ship's bow large enough to drive a truck through, but the Maumee was able to travel halfway around the world to a repair yard, without difficulty, because she was fitted with watertight bulkheads.

[163] The Marine Board noted that because Edmund Fitzgerald lacked a draft-reading system, the crew had no way to determine whether the vessel had lost freeboard (the level of a ship's deck above the water).

[136] NTSB investigators noted that Edmund Fitzgerald's prior groundings could have caused undetected damage that led to major structural failure during the storm, since Great Lakes vessels were normally drydocked for inspection only once every five years.

[136] After August B. Herbel Jr., president of the American Society for Testing and Materials, examined photographs of the welds on Edmund Fitzgerald, he stated, "the hull was just being held together with patching plates."

Other questions were raised as to why the USCG did not discover and take corrective action in its pre-November 1975 inspection of Edmund Fitzgerald, given that her hatch coamings, gaskets, and clamps were poorly maintained.

He said, "in my opinion, all the subsequent events arose because (McSorley) kept pushing that ship and didn't have enough training in weather forecasting to use common sense and pick a route out of the worst of the wind and seas.

The Marine Board feels that this attitude reflects itself at times in deferral of maintenance and repairs, in failure to prepare properly for heavy weather, and in the conviction that since refuges are near, safety is possible by "running for it."

[181] Robert Hemming, a reporter and newspaper editor, reasoned in his book about Edmund Fitzgerald that the USCG's conclusions "were benign in placing blame on [n]either the company or the captain ... [and] saved the Oglebay Norton from very expensive lawsuits by the families of the lost crew.

[172] Of the official recommendations, the following actions and USCG regulations were put in place: Karl Bohnak, an Upper Peninsula meteorologist, covered the sinking and storm in a book on local weather history.

On August 8, 2007, along a remote shore of Lake Superior on the Keweenaw Peninsula, a Michigan family discovered a lone life-saving ring that appeared to have come from Edmund Fitzgerald.

Also, in light of new evidence about what happened, Lightfoot modified one line for live performances, the original stanza being: When suppertime came the old cook came on deck, Saying "Fellas, it's too rough to feed ya."

[213][a] In November 2000, Shelley Russell opened a production of her play, Holdin' Our Own: The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, at the Forest Roberts Theatre on the campus of Northern Michigan University.