1969 Santa Barbara oil spill

The public outrage engendered by the spill, which received prominent media coverage in the United States, resulted in numerous pieces of environmental legislation within the next several years, legislation that forms the legal and regulatory framework for the modern environmental movement in the U.S.[3][4][5][6][7] Because of the abundance of oil in the thick sedimentary rock layers beneath the Santa Barbara Channel, the region has been an attractive resource for the petroleum industry for more than a hundred years.

[10] Oil development in the Channel and adjacent coastline was controversial even from the earliest days, as by the late 19th century the city was beginning to establish itself as a health resort and tourist destination with dramatic natural scenery, unspoiled beaches, and a perfect climate.

In the late 1890s, when the Summerland field began to expand much closer to the city of Santa Barbara, a crowd of midnight vigilantes headed by local newspaper publisher Reginald Fernald tore down one of the more unsightly rigs erected on Miramar Beach itself (in 2010 the location of a luxury hotel).

While local protests were vocal, they failed to shut down the oil development, as there was a city ordinance at the time specifically allowing drilling on the Mesa.

Seismic testing under the Channel began shortly after the Second World War, in an attempt to locate the suspected petroleum reservoirs deep underneath the ocean floor.

The testing was noisy and disruptive; explosions rattled windows, cracked plaster, and filled the beaches with dead fish; local citizens as well as the Santa Barbara News-Press vocally opposed the practice, which continued nonetheless, but after a delay and under tighter controls.

Yet the testing had revealed what the oil company geologists had suspected, and the population feared: the probable presence of sizeable exploitable petroleum reservoirs in relatively shallow water, approximately 200 feet (60 m) deep, within reach of developing ocean-drilling technology.

[13]: 90–92 A series of legal and legislative actions, however, delayed actual oil platform construction and drilling until the mid-1960s, as the Federal and State governments fought for ownership of submerged lands.

This was possible because a 1965 Supreme Court decision finally settled the competing claims on the submerged lands outside of 3 miles (5 km) limit, giving them to the federal government.

After the workers pulled the drill bit out, with some difficulty, an enormous spout of oil, gas, and drilling mud burst into the air into the rig, splattering the men with filth; several of them attempted to screw a blowout-preventer onto the pipe, but against a pressure of over 1,000 pounds per square inch (7 MPa), this proved to be impossible; all workers except for those engaged in the plugging attempt were evacuated, due to the danger of explosion from the abundant natural gas blown from the hole; finally, the workers tried the method of last resort, dropping the remaining drill pipe – almost 0.5 miles (800 m) long – into the hole, and then crushing the top of the well pipe from the sides with a pair of "blind rams", enormous steel blocks slamming together with force sufficient to stop anything from escaping from the well.

[17] The first announcement of the potential disaster was made by Don Craggs, Union Oil's regional superintendent to Lieutenant George Brown of the U.S. Coast Guard, about two and a half hours after the blowout.

An anonymous worker on the drill rig telephoned the Santa Barbara News-Press regarding the blowout, and the newspaper immediately obtained confirmation from Union Oil's headquarters in Los Angeles.

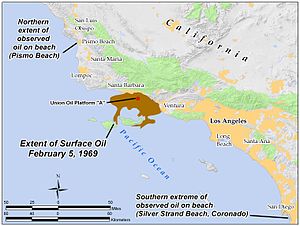

[22] Combined with the prevailing north-northwesterly winds typical of the area between storm systems, this pushed the expanding oil slick away from the shore, and it seemed for several days that the beaches of Santa Barbara would be spared.

[13]: 54–5 On the morning of February 5, residents of the entire populated zone on the coast awoke to the stink of crude oil, and the sight of blackened beaches, sprinkled with dead and dying birds.

[13]: 57–8 The sound of the waves breaking was eerily muted by the thick layer of oil, which accumulated on shore in some places to a depth of 6 inches (150 mm).

The same morning, a U.S. Senate subcommittee interviewed local officials as well as Fred Hartley, president of Union Oil, on the disaster in the making.

Three major television networks were there along with over 50 reporters, the largest media turnout for any Senate subcommittee meeting since the Committee on Foreign Relations discussed the Vietnam War.

[13]: 66 During the meeting, local officials made their case that the Federal government had a conflict of interest, in that they were making money from the same drilling they were mandated to oversee and regulate.

Local officials, not invited to the meeting, were furious that "complete reevaluation and reassessment" could have occurred in such a short time, and in a meeting that excluded them; the fierce exchange was covered on national television, along with grim footage of the thousands of dying birds on the tarred beaches of Santa Barbara, and the spontaneous efforts of hundreds of civilian volunteers to pile straw on the oil, scrub rocks with detergent, and struggle to save a few of the less-oiled birds.

[13]: 76 Still the spill continued to spew from fissures in the ocean floor, undiminished, and by noon on February 7 a $1.3 billion class action lawsuit had been filed against Union Oil and their partners on Platform A.

They made their final attempt that afternoon and evening, pumping 13,000 barrels (2,100 m3) of the heaviest available drilling mud into the well at pressures of thousands of pounds per square inch.

Arriving at the Point Mugu Naval Air Station, he then took a helicopter tour of the Santa Barbara Channel, Platform A, and the polluted, partially cleaned beaches.

Authors of a Marine Fisheries Review study were unwilling to make a firm link with the oil spill, since other variables such as water temperature and a subsequent El Niño year could not be ruled out as causes of the divergence.

In a "no strings attached"[13]: 140 study funded by the Western Oil and Gas Association, through the Allan Hancock Foundation at the University of Southern California, the authors suggested several hypotheses for the lack of environmental damage to biologic resources in the Channel aside from pelagic birds and intertidal organisms.

Fourth, Santa Barbara Channel crude oil is heavy, having API gravity between 10 and 13, and is both minimally soluble in water, and sinks relatively easily.

[4] Through the 1960s, industrial pollution and its consequences had come more and more to the public attention, commencing with Rachel Carson's 1962 book Silent Spring and including such events as the passage of the Water Quality Act, the campaign to ban DDT, the creation of the National Wilderness Preservation System, the 1967 Torrey Canyon tanker accident which devastated coastal areas in both England and France, and the burning of the Cuyahoga River in downtown Cleveland, Ohio.

Officials from the Federal Water Pollution Control Administration, created only in 1965, came to Santa Barbara to oversee not only the cleanup but the effort to plug the well.

[3][42] NEPA in particular completely changed the regulatory situation, in that it required that all projects by any federal government agency be scrutinized for their potential adverse environmental impacts prior to approval, including a period for public comment.

A proposal to slant drill into the state-controlled zone from an existing platform outside of it, on the Tranquillon Ridge, was rejected in 2009 by the State Lands Commission by a 2–1 vote.

The same people who organized this event, led by Marc McGinnes, had been working closely with Congressman Pete McCloskey (R-CA) for the creation of the National Environmental Policy Act.