Santo Tomas Internment Camp

Japan attacked the Philippines on December 8, 1941, the same day as its raid on Pearl Harbor (on the Asian side of the International Date Line).

On the same day, the Japanese invaded several locations in northern Luzon and advanced rapidly southward toward Manila, capital and largest city of the Philippines.

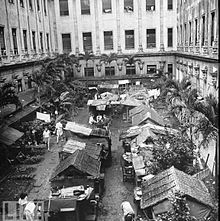

[4] Thousands of people, mostly Americans and British, staked out living and sleeping quarters for themselves and their families in the buildings of the university.

The Japanese mostly let the foreigners fend for themselves except for appointing room monitors and ordering a 7:30 p.m. roll call every night.

The Japanese put a stop to that by ordering the fence to be shielded by bamboo mats but they permitted parcels to enter the compound after being searched.

In the early days of STIC, as it was called by internees, the Japanese did not provide food so it was purchased with loans from the Red Cross and donations from individuals.

"[9] The cooperation of the internees permitted the Japanese to control the camp with a minimum of resources and personnel, amounting at times to only 17 administrators and 8 guards.

[10] The number of internees in February 1942 amounted to 3,200 Americans, 900 British (including Canadian, Australian, and other Commonwealth people), 40 Poles, 30 Dutch, and individuals from Spain, Mexico, Nicaragua, Cuba, Russia, Belgium, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, China, and Burma.

The internees were diverse: business executives, mining engineers, bankers, plantation owners, seamen, shoemakers, waiters, beachcombers, prostitutes, retired soldiers from the Spanish–American War, 40 years earlier, missionaries, and others.

Their tasks included building more toilets and showers, laundry, dishwashing, and cooking facilities, disposal of garbage, and controlling the flies, mosquitoes, and rats that infested the compound.

As news of the surrender of American forces at Bataan and Corregidor seeped into the camp, the internees settled in for a long stay.

After the votes were counted, the Japanese exercised their prerogative by announcing that Carroll C. Grinnell, who had placed sixth in the election, was appointed as the chairman of a seven-person executive committee.

In succeeding months, more men and families were transferred to Los Baños including a large number of missionaries and clergymen who were previously allowed to remain outside the internment camps provided they pledged not to engage in politics.

Described as a "delightful spot" on arrival, conditions at Los Baños became increasingly crowded and difficult toward the end of the war, mirroring the situation at Santo Tomas.

[25] The population of Los Baños totaled 2,132, including a three-day-old baby, when it was liberated by American soldiers and Filipino guerrillas on February 23, 1945.

[26] As the war in the Pacific turned against Japan, living conditions in Santo Tomas became worse and Japanese rule over the internees more oppressive.

The distress caused by the typhoon, however, was soon relieved by the receipt in the camp of Red Cross food parcels just before Christmas.

Every internee, including children, received a parcel weighing 48 pounds (21.8 kg) and containing luxuries such as butter, chocolate, and canned meat.

These were the only Red Cross parcels received by the internees during the war and undoubtedly staved off malnutrition and disease, reducing the death rate in Santo Tomas.

After July 1944, "the food at the camps became extremely inadequate, weight loss, weakness, edema, paresthesia and beriberi were experienced by most adults."

That same day the Japanese confiscated much of the food left in the camp for their soldiers and the "cold fear of death" gripped the weakened internees.

[37] A small American force pushed rapidly forward and, on February 3, 1945, at 8:40 p.m., internees heard the sound of tanks, grenades, and rifle fire near the front wall of Santo Tomas.

He was carried away by a mob of enraged internees, kicked and slashed with knives, and thrown out of a hospital bed onto the floor.

[40] In the words of an American military officer, the British missionary of the "Two by Twos" Ernest Stanley was "the most hated man in camp.

His negotiation efforts initially failed, and American tanks bombarded the building, first warning the hostages within to take cover.

[42] Stanley led the Japanese out of the building and accompanied them to their place of release, an event recorded by a photograph that appeared in Life magazine.

[44] The formation got lost, and upon reaching Legarda Street near present-day Nagtahan Flyover, the Japanese prison guards headed by Col. Toshio Hayashi, were ambushed by Filipino guerrillas.

Sixty-four U.S. Army and Navy nurses interned in Santo Tomas were the first to leave that day and board airplanes for the United States.

[43] Earl Carroll defended himself and other camp leaders from allegations of collaboration in a series of newspaper articles in which he claimed the internees had waged a "secret war" against the Japanese.

By working with the internees, the Japanese suppressed resistance, isolated Americans from Filipinos, freed up resources, and exploited the camp for intelligence and propaganda.