Sarah Bernhardt

She played Henriette in Molière's Les Femmes Savantes and Hippolyte in L'Étourdi, and the title role in Scribe's Valérie, but did not impress the critics, or the other members of the company, who had resented her rapid rise.

The co-director of the theatre for finance, Charles de Chilly, wanted to reject her as unreliable and too thin, but Duquesnel was enchanted; he hired her for the theater at a modest salary of 150 francs a month, which he paid out of his own pocket.

[45] Her next success was her performance in François Coppée's Le Passant, which premiered at the Odéon on 14 January 1868,[46] playing the part of the boy troubadour, Zanetto, in a romantic renaissance tale.

[52] She organised the placement of 32 beds in the lobby and the foyers, brought in her personal chef to prepare soup for the patients, and persuaded her wealthy friends and admirers to donate supplies for the hospital.

By the end of the siege, Bernhardt's hospital had cared for more than 150 wounded soldiers, including a young undergraduate from the École Polytechnique, Ferdinand Foch, who later commanded the Allied armies in the First World War.

A few months after it opened, Bernhardt received an invitation from Emile Perrin, Director of the Comédie Française, asking if she would return, and offering her 12,000 francs a year, compared with less than 10,000 at the Odéon.

When she returned by train to the city, Perrin was furious; he fined Bernhardt a thousand francs, citing a theatre rule which required actors to request permission before they left Paris.

Furthermore, the Gaiety Theatre in London demanded that Bernhardt star in the opening performance, contrary to the traditions of Comédie Française, where roles were assigned by seniority, and the idea of stardom was scorned.

[71] In April 1880, as soon as he learned Bernhardt had resigned from the Comédie Française, the impresario Edward Jarrett hurried to Paris and proposed that she make a theatrical tour of England and then the United States.

Her impresario, Edouard Jarrett, immediately proposed she make another world tour, this time to Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Peru, Panama, Cuba, and Mexico, then on to Texas, New York City, England, Ireland, and Scotland.

However, the senior members of the company protested the high salary offered, and conservative defenders of the more traditional theatre also complained; one anti-Bernhardt critic, Albert Delpit of Le Gaulois, wrote "Madame Sarah Bernhardt is forty-three; she can no longer be useful to the Comédie.

[115] At the Théâtre de la Renaissance, Bernhardt staged and performed in several modern plays, but she was not a follower of the more natural school of acting that was coming into fashion at the end of the 19th century, preferring a more dramatic expression of emotions.

Bernhardt was forced to give up the Renaissance, and was preparing to go on another world tour when she learned that a much larger Paris theater, the Théâtre des Nations on Place du Châtelet, was for lease.

The theatre had 1,700 seats, twice the size of the Renaissance, enabling her to pay off the cost of performances more quickly; it had an enormous stage and backstage, allowing her to present several different plays a week; and because it was designed as a concert hall, it had excellent acoustics.

The play inspired the creation of Bernhardt souvenirs, including statuettes, medallions, fans, perfumes, postcards of her in the role, uniforms and cardboard swords for children, and pastries and cakes; the famed chef Escoffier added Peach Aiglon with Chantilly cream to his repertoire of desserts.

She attracted controversy and press attention when, during her 1905 visit to Montreal, the Roman Catholic bishop encouraged his followers to throw eggs at Bernhardt, because she portrayed prostitutes as sympathetic characters.

[133] Her tour continued into South America, where it was marred by a more serious event: at the conclusion of La Tosca in Rio de Janeiro, she leaped, as always, from the wall of the fortress to plunge to her death in the Tiber.

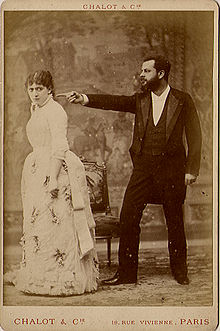

She took along a new leading man, the Dutch-born Lou Tellegen, a very handsome actor who had served as a model for the sculpture Eternal Springtime by Auguste Rodin, and who became her co-star for the next two years, as well as her escort to all events, functions, and parties.

She recuperated for several months, with her condition improving; she began preparing for a new role as Cleopatra in Rodogune by Corneille, and agreed to make a new film by Sasha Guitry called La Voyante, for a payment of 10,000 francs a day.

Maurice's finished two-minute film, Le Duel d'Hamlet, was presented to the public at the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition from 14 April to 12 November 1900 in Paul Decauville's program, Phono-Cinéma-Théâtre.

Then, in 1912, the pioneer American producer Adolph Zukor came to London and filmed her performing scenes from her stage play Queen Elizabeth with her lover Tellegen, with Bernhardt in the role of Lord Essex.

[162] She quickly picked up the techniques; she exhibited and sold a high-relief plaque of the death of Ophelia and, for the architect Charles Garnier, she created the allegorical figure of Song for the group Music on the façade of the Opera House of Monte Carlo.

She encouraged actors to "Work, overexcite your emotional expression, become accustomed to varying your psychological states and translating them...The diction, the way of standing, the look, the gesture are predominant in the development of the career of an artist.

"[56] Reviewing her performance of Ruy Blas in 1872, the critic Théodore de Banville wrote that Bernhardt "declaimed like a bluebird sings, like the wind sighs, like the water murmurs.

"[176] Her 1882 performance of Fédora was described by the English novelist Maurice Baring: "A secret atmosphere emanated from her, an aroma, an attraction which was at once exotic and cerebral...She literally hypnotized the audience", and played "with such tigerish passion and feline seduction which, whether it be good or bad art, nobody has been able to match since.

In her autobiography, Ma Double Vie,[186] she describes meeting her father several times, and writes that his family provided funding for her education, and left a sum of 100,000 francs for her when she came of age.

"[190] A more recent biography by Hélène Tierchant (2009) suggests her father may have been a young man named De Morel, whose family members were notable shipowners and merchants in Le Havre.

According to Bernhardt's autobiography, her grandmother and uncle in Le Havre provided financial support for her education when she was young, took part in family councils about her future, and later gave her money when her apartment in Paris was destroyed by fire.

She was one of six children, five daughters and one son, of a Dutch-Jewish itinerant eyeglass merchant, Moritz Baruch Bernardt, and a German laundress,[194] Sara Hirsch (later known as Janetta Hartog or Jeanne Hard).

He had little acting experience, but Bernhardt signed him as a leading man just before she departed on the tour, assigned him a compartment in her private railway car, and took him as her escort to all events, functions, and parties.