Sara G. Stanley

Sara Griffith Stanley Woodward (1837 – 1918) was an African American abolitionist, missionary teacher, and published author.

She wrote and published several abolitionist works in journal magazines, but her most famous writing was an address on behalf of the Delaware Ladies' Antislavery Society given at the State Convention of Colored Men during the 1856 election year.

[4][5] Coming from a respected and well-known family allowed the Stanleys to open a school for black children in New Bern.

When he wasn't helping his father with his businesses and plantation, John and his wife Fannie were teachers at their school, thus allowing Sara to lead an academic centered life from a young age.

[6][7] As a child, Stanley attended the First Presbyterian Church and sat in one of the back two pews that were purchased by her grandfather John Carruthers Stanly.

[3][10] The heightened racial tensions resulting from resentment toward free blacks and the increased restrictions led Stanley's father and others to close schools for children of color.

However, Ellen NicKenzie Lawson argued in her book that "the petition has all the earmarks of Stanley's literary style, so it seems likely the typesetter misprinted her last name leaving out the "n".

[9] In 1867, Stanley wrote a short article in the American Missionary about an interview she conducted with an elderly woman from Mississippi who recalled her life as a slave.

Horrified by the interview, Sara wrote: "Surely many a lessen of patient endurance in the difficulties which beset our work, may we learn from these lowly ones.

[2] The purpose of the integrated organization was the "abolition of slavery, education of African Americans, promotion of racial equality, and spreading Christian values".

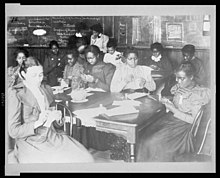

[15] By May, Stanley was sent to Norfolk, Virginia for her first teaching assignment at the Bute Street School, where she taught African American students who had been recently emancipated from slavery.

[6] Another conflict occurred involving Stanley and white teacher, Mrs. Gleason, who expressed her displeasure with working alongside African American staff.

[2] Although Stanley was allowed to stay with the AMA after the incident, two months later, she was sent to work St. Louis, Missouri, where her next school was a "small, windowless room in a church basement".

The Caucasian element is largely ascendant, many of the children have blond and red hair and the peculiarly white transparent complexion which is their usual accompaniment.

During her time there, the AMA was slow to send her salary and travel money, but Stanley refused to accept tuition from indigent students.

[16] While on assignment for AMA in Alabama, 1868, Stanley met Charles A. Woodward, a white man who had served in the Union army during the Civil War.

Local whites were already critical over the expansion of colored education and were further agitated over the rumors of the possibility of the Woodwards marrying in the new Mission House.

[6] In 1894, Stanley briefly taught with notable abolitionist and educator Lucy Craft Laney at a small school for black women in Augusta, Georgia.