Sardis

After the fall of the Lydian Empire, it became the capital of the Persian satrapy of Lydia and later a major center of Hellenistic and Byzantine culture.

Early Bronze Age cemeteries were found 7 miles away along Lake Marmara, near elite graves of the later Lydian and Persian periods.

[1](p1116)[2] In the Late Bronze Age, the site would have been in the territory of the Seha River Land, whose capital is thought to have been located at nearby Kaymakçı.

Settlement extended to the Pactolus Stream, near which archaeologists have found the remains of work installations where alluvial metals were processed.

[1](p1117) Textual evidence regarding Lydian-era Sardis include Pliny's account of a mudbrick building that had allegedly been the palace of Croesus and was still there in his own time.

In the words of excavator Nicholas Cahill: It is rare that an important and well-known historical event is so vividly preserved in the archaeological record, but the destruction of Cyrus left clear and dramatic remains throughout the city.

One soldier's forearm bones had been snapped, likely a parry fracture indicating a failed attempt to counter the head injuries that killed him.

Household implements such as iron spits and small sickles were found mixed in with ordinary weapons of war, suggesting that civilians attempted to defend themselves during the sack.

The city may even have been rebuilt outside the limits of the Lydian-era walls, as evidenced by authors such as Herodotus who place the Persian era central district along the Pactolus stream.

[6] The material culture of the city was largely continuous with the Lydian era, to the point that it can be hard to precisely date artifacts based on style.

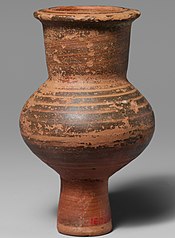

[1](pp1120–1122) Notable developments of this period include adoption of the Aramaic script alongside the Lydian alphabet and the "Achaemenid bowl" pottery shape.

In particular, jewelers turned to semi-precious stones and colored frit due to a Persian prohibition on gold jewelry among the priestly class.

Textual evidence suggests that the city was known for its paradisoi as well as orchards and hunting parks built by Tissaphernes and Cyrus the Younger[1](p1122) Burials of this period include enormous tumuli with extensive grave goods.

For the next two centuries, the city passed between Hellenistic rulers including Antigonus Monophthalmos, Lysimachus, the Seleucids, and the Attalids.

These new buildings included a prytaneion, gymnasion, theater, hippodrome, as well as the massive Temple of Artemis still visible to modern visitors.

The city received three neocorate honors and was granted ten million sesterces as well as a temporary tax exemption to help it recover after a devastating earthquake in 17 AD.

[citation needed] During the cataclysmic 7th-century Byzantine–Sasanian War, Sardis was in 615 one of the cities sacked in the invasion of Asia Minor by the Persian Shahin.

[citation needed] Sardis retained its titular supremacy and continued to be the seat of the metropolitan bishop of the province of Lydia, formed in 295 AD.

Its citadel was built on Mount Tmolus, a steep and lofty spur, while a lower town extended to the area of the Pactolus stream.

Early excavators included the British explorer George Dennis, who uncovered an enormous marble head of Faustina the Elder.

Found in the precinct of the Temple of Artemis, it probably formed part of a pair of colossal statues devoted to the Imperial couple.

[11] The first large-scale archaeological expedition in Sardis was directed by a Princeton University team led by Howard Crosby Butler between years 1910–1914, unearthing a temple to Artemis, and more than a thousand Lydian tombs.

Hanfmann excavated widely in the city and the region, excavating and restoring the major Roman bath-gymnasium complex, the synagogue, late Roman houses and shops, a Lydian industrial area for processing electrum into pure gold and silver, Lydian occupation areas, and tumulus tombs at Bintepe.

[15] Some of the important finds from the site of Sardis are housed in the Archaeological Museum of Manisa, including Late Roman mosaics and sculpture, a helmet from the mid-6th century BC, and pottery from various periods.