Byzantine Empire

[2] The adjective "Byzantine", derived from Byzantion (Byzantium in Latin), the name of the Greek settlement Constantinople was established on, was only used to describe the inhabitants of the city; it did not refer to the empire, called Romanía ("Romanland") by its citizens.

The Roman Empire enjoyed a period of relative stability until the third century AD, when external threats and internal instabilities caused it to splinter, as regional armies acclaimed their generals as "soldier-emperors".

[18] Valens's successor, Theodosius I (r. 379–395), restored political stability in the east by allowing the Goths to settle in Roman territory;[19] he also twice intervened in the western half, defeating the usurpers Magnus Maximus and Eugenius in 388 and 394 respectively.

[21] He was the last emperor to rule both the western and eastern halves of the empire;[22] after his death, the West was destabilised by a succession of "soldier-emperors", unlike the East, where administrators continued to hold power.

[25] After Leo I (r. 457–474) failed in his 468 attempt to reconquer the West, the warlord Odoacer deposed Romulus Augustulus in 476, killed his titular successor Julius Nepos in 480, and the office of western emperor was formally abolished.

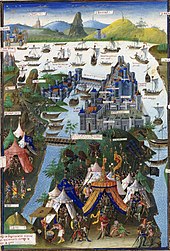

[30] Following his accession in 527, the legal code was rewritten as the Corpus Juris Civilis and Justinian produced extensive legislation on provincial administration;[31] he reasserted imperial control over religion and morality through purges of non-Christians and "deviants";[32] and having ruthlessly subdued the 532 Nika revolt he rebuilt much of Constantinople, including the original Hagia Sophia.

[35] The emperor's internal reforms and policies began to falter, and a devastating plague killed a large proportion of the population and severely weakened the empire's social and financial stability.

[49] The outbreak of the First Fitna in 656 gave Byzantium breathing space, which it used wisely: some order was restored in the Balkans by Constans II (r. 641–668),[50] and the administrative reorganisation implemented by him known as the "theme system", which allocated troops to defend specific provinces.

[56] Leo and his son Constantine V (r. 741–775), two of the most capable Byzantine emperors, withstood continued Arab attacks, civil unrest, and natural disasters, and reestablished the state as a major regional power.

[59] Constantine overcame an early civil war against his brother-in-law Artabasdos, made peace with the new Abbasid Caliphate, campaigned successfully against the Bulgars, and continued to make administrative and military reforms.

These included the Basilika, a Greek translation of Justinian I's legal code incorporating over 100 new laws created by Leo; the Tactica, a military treatise; and the Book of the Eparch, a manual on Constantinople's trading regulations.

[80] His son and successor died young; under two soldier-emperors, Nikephoros II (r. 963–969) and John I Tzimiskes (r. 969–976), the army claimed numerous military successes, including the conquest of Cilicia and Antioch, and a sensational victory against Bulgaria and the Kievan Rus' in 971.

[89] This political instability, regular budget deficits, a series of expensive military failures, and other problems connected to over-extension led to substantial issues in the empire;[90] its strategic focus moved from maintaining its hegemony to prioritising defence.

[92] In 1071 Bari, the last remaining Byzantine settlement in Italy, was captured by the Normans, while the Seljuks won a decisive victory at the Battle of Manzikert, taking the emperor Romanos IV Diogenes prisoner.

In contrast to the prior turmoil, the three reigns of Alexios (r. 1081–1118), his son John II (r. 1118–1143), and his grandson Manuel I (r. 1143–1180) lasted a century and restored the empire's regional authority for the final time.

[103] Through a combination of diplomacy and bribery, he cultivated a ring of allies and clients around the empire: the Turks of the Sultanate of Rum, the Kingdom of Hungary, the Cilician Armenians, Balkan princes, Italian and Dalmatian cities, and most importantly Antioch and the Crusader States, marrying one of their princesses in 1161.

[116] For a time, it seemed that Epirus was the one most likely to reclaim Constantinople from the Latins, and its ruler Theodore Doukas crowned himself emperor, but he suffered a critical defeat at the Battle of Klokotnitsa in 1230, and Epirote power waned.

[117] Nicaea, ruled by the Laskarid dynasty and composed of a mixture of Byzantine refugees and native Greeks, blocked the Latins and the Seljuks of Rum from expanding east and west respectively.

[185] Mercenary armies further fuelled political divisions and civil wars; these led to a collapse in the Empire's defence, and resulted in significant losses of territories such as Italy and the Anatolian heartland in the 11th century.

[248] The empire's geographic and maritime advantages reduced the costs of transporting goods and facilitated trade, making it a key driver of economic growth from antiquity and through the post-classical period.

[265] Despite these challenges, the empire's mixed economy (characterised by state interventions, public works, and market liberalisation)[266] remained a model of medieval economic adaptability, even as it deteriorated under external pressures.

[315] The early 6th-century reign of Justinian I saw systemic developments: religious art came to dominate, and once-popular public marble and bronze monumental sculpture fell out of favour due to pagan associations.

[320] Other costly objects included illuminated manuscripts, which were lavishly illustrated for a wide range of texts, and silks, often dyed in the prized imperial purple; both became highly popular in Western Europe.

[326] Subjects and styles became standardised, particularly cross-in-square churches, and already-existing frontality and symmetry evolved into a dominant artistic aesthetic, observable in the small Pala d'Oro enamel and the large mosaics of the Hosios Loukas, Daphni, and Nea Moni monasteries.

[328] As smaller Palaeologan artworks (1261–1453) gained relic status in Western Europe—many looted in the 1204 Fourth Crusade—they greatly influenced the Italo-Byzantine style of Cimabue, Duccio, and later Giotto; the latter is traditionally regarded by art historians as the inaugurator of Italian Renaissance painting.

[336] A new generation (c. 1000–1250), including Symeon, Michael Psellos and Theodore Prodromos, rejected the Encyclopedist emphasis on order, and were interested in individual-focused ideals variously concerning mysticism, authorial voice, heroism, humour and love.

[349] By the Palaiologan period, the dominance of strict compositional rules lessened and John Koukouzeles led a new school favouring a more ornamental "kalophonic" style which deeply informed post-empire Neo-Byzantine music.

[361] Military innovations included the riding stirrup which provided stability for mounted archers and dramatically transformed the army; a specialised type of horseshoe; the lateen sail, which improved a ship's responsiveness to wind; and Greek fire—an incendiary weapon capable of burning even when doused with water, first appearing around the time of the Siege of Constantinople (674–678).

[365] As the sole sovereign Orthodox state, Russia developed the Third Rome doctrine, emphasising its cultural heritage as distinct from Western Europe, because the latter had inherited much of the empire's secular learning.

[373] The Byzantine Empire distinctively blended Roman political traditions, Greek literary heritage, and Christianity, creating the civilisational framework that laid the foundation for medieval Europe.